Animals in this Exhibit

Try to spot the brilliant colors of the rhino viper, or see if you can get a glimpse of the elusive timber rattlesnake. Because many of the animals are naturally camouflaged, Zoo volunteers are stationed around the exhibit to point out where animals are “hiding” to visitors.

At the Jewels of Appalachia exhibit, visitors can peer into the underground world of salamanders and learn about how these tiny creatures are critical to an entire ecosystem, as well as what Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute scientists are doing to save them. In the research lab, visitors can catch a behind-the-scenes look at the Zoo's salamander science, which measures the effects of climate change and other environmental stressors on salamanders.

Unlike some of the Zoo's other animals, the inhabitants of the Reptile Discovery Center won't be found outside during the wintertime. These ectothermic (cold-blooded) creatures rely on the temperature of their surrounding environment to maintain their body temperature, so they can’t withstand the cold, wintry weather.

Reptile Discovery Center keepers provide the animals with enrichment — enclosures, socialization, objects, sounds, smells and other stimuli — to enhance their well-being and give them an outlet to demonstrate their species-typical behaviors. An exhibit’s design is carefully and deliberately planned to provide physically and mentally stimulating toys, activities, and environments for the Zoo’s animals. Each enrichment is tailored to give an animal the opportunity to use its natural behaviors in novel and exciting ways.

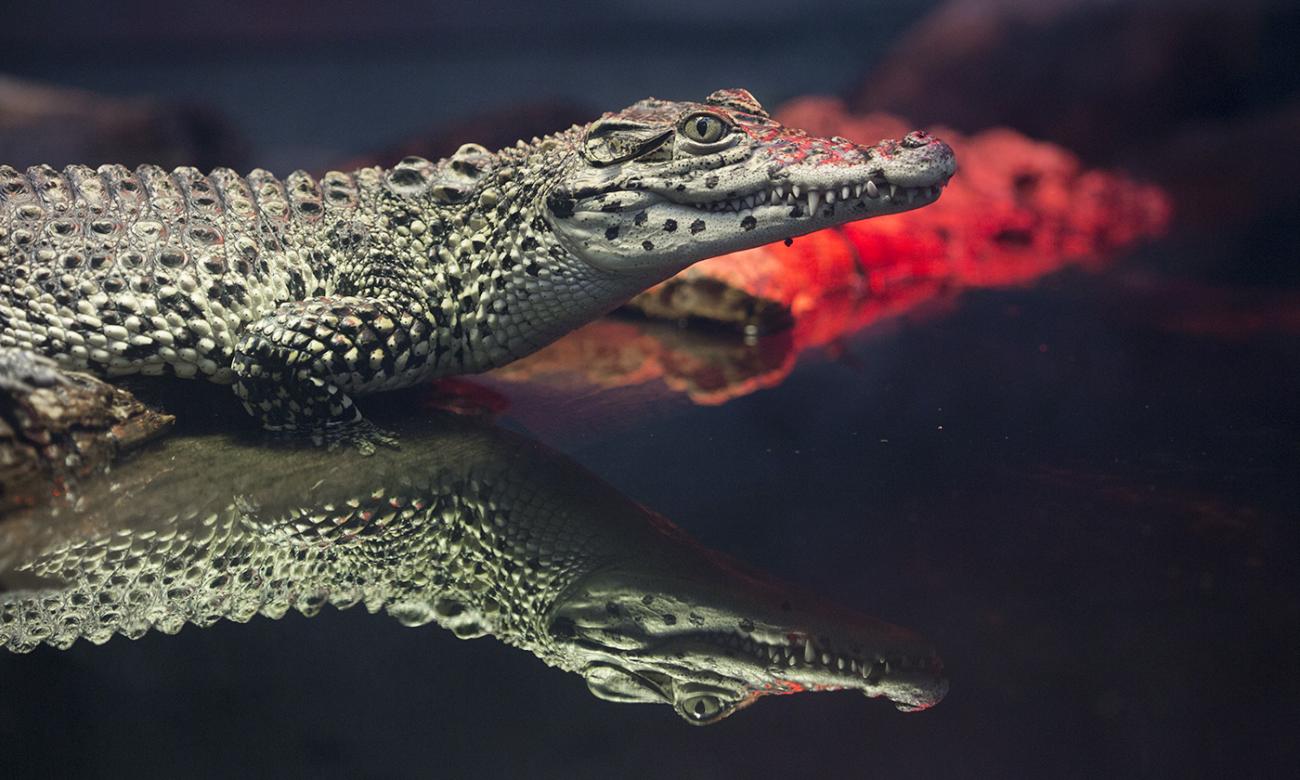

Enclosures were designed to mimic the animals’ wild habitats and encourage natural behaviors. Cuban crocodiles, for example, have the option to spend their time swimming in their pools or resting on dry land.

Keepers will often scatter and hide food throughout the exhibits or in puzzle feeders to encourage foraging and problem-solving. A green tree monitor’s enclosure includes a branch drilled with holes of varying sizes. Keepers will place insects within each hole, and the lizard must use its mouth and dexterous hands to reach the food inside, just as it would in the wild.

In addition to environmental enrichment, many animals participate in training sessions. This social enrichment provides an animal with exercise and mental stimulation while reinforcing the relationship between an animal and his/her keeper. Keepers are training the Zoo’s crocodiles and alligators to voluntarily participate in blood draws for health checkups and veterinary exams. Keepers cue the animals to move to an area where they can get close to the animals, but with a safety barrier in between. Once keepers get an animal comfortable with his/her tail being touched, Zoo veterinarians can then take a blood sample. Read more about training crocodiles and alligators in the Zoo’s Croc and Gator news feed.

Positive reinforcement training enables the keepers to move animals, clean their habitats, feed them and perform other husbandry-related tasks. Part of managing animals is keeping track of their weight and ensuring they are in the best condition. Keepers are training the Grand Cayman iguanas to station (hold still) on a scale. Both iguanas tend to be more curious than cautious when it comes to new items being presented to them, especially if food is involved. As they climb upon the scale, keepers offer them fruit rewards. Regularly training this behavior is essential to maintaining a consistent, stress-free and fun way to weigh the iguanas.

Great Apes is located uphill from the Reptile Discovery Center; Think Tank is located downhill from Reptile Discovery Center; Lemur Island is located across from Reptile Discovery Center. Visitors can observe western lowland gorillas, Bornean and Sumatran orangutans, Allen’s swamp monkeys, ring-tailed lemurs and more at these locations.

The Great Meadow picnic area is located across from Reptile Discovery Center.

Frogs

In 1999, Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute scientists working with a researcher at the University of Maine described a chytrid fungus that causes the deadly amphibian skin disease chytridiomycosis. Since then, the understanding of amphibian declines and this disease has improved greatly. Scientists now suspect that amphibian chytrid fungus originated in Southern Africa. Chytrid threatens amphibians in the biodiverse hotspots of Central and South America, with more than 25 to 30 species currently at risk.

The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project (PARCP) was launched in 2009 as a partnership between Africam Safari, Defenders of Wildlife, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Houston Zoo, the Smithsonian National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, Summit Municipal Park, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and Zoo New England. The goal is to build resources and improve expertise in Panama so that Panamanians could conserve their unique biodiversity of amphibians. On April 8, 2015, PARCP opened a rescue lab at the Gamboa Amphibian Research and Conservation Center to house colonies of amphibians threatened by the deadly Chytrid fungus.

Salamanders

The Appalachian region is home to more salamander species than anywhere else in the world, making it a true hotspot for salamander biodiversity. Thanks to the area’s diverse forest and freshwater ecosystems, many different salamander species have adapted to the relatively cool, mid- and high-elevation highlands. With almost half of all salamander species listed as threatened or endangered and populations already declining, the Appalachian region has become a primary focus of salamander conservation research and planning.

Since salamanders cannot be protected from climate change in the same way that pollution or habitat loss can be mitigated, SCBI and Zoo staff are working to determine how each particular species will be affected in order to develop effective strategies to help them survive. This includes making detailed observations of the physiology of different species, their current ranges, and ability to withstand or adapt to climate change. A few species may adapt relatively easily to a warmer, more variable climate. Ensuring that “corridors” are available for migration of salamanders northward to healthy, cooler habitats may work for other salamanders. Mountaintop species may require relocation if they become too pressured by climate change or competitive species. Finally, raising salamanders in human care will establish an assurance colony to guard against extinction in the wild and provide more opportunities for research.

Hellbenders

The hellbender is a large, aquatic salamander native to cold, fast-flowing Appalachian streams. It uses its rudimentary lungs primarily for buoyancy, and it has no gills, so it breathes through its very wrinkled skin. Because warm water holds less oxygen than cold water, hellbenders may be even more at risk to climate change then terrestrial salamanders. To understand this risk, researchers at SCBI are studying hellbenders both in the wild and in controlled lab-based studies. By examining how temperature and water quality influence stress indicators, metabolism, and immune function, researchers can develop effective management strategies to ensure the survival of this unique species.

Japanese Giant Salamanders

With so many threats facing the Japanese giant salamander, the Asa Zoo and Smithsonian's National Zoo have teamed up to create a breeding colony outside of Japan. Toward that end, the Asa Zoo gave six of its salamanders to the Zoo’s Asia Trail and Reptile Discovery Center exhibits. In addition to studying how Japanese giant salamanders reproduce, Zoo and SCBI scientists are studying this species to learn about the chytrid fungus that is lethal to some amphibian species but does not seem deadly to the Japanese giant salamander. In this way, these salamanders may contribute not only to their own species’ survival but to the survival of amphibians around the globe.