By Investigating Death, Kali Holder Gathers Lessons on Life

It is a truism that “in the midst of life, we are in death,” and the sad fact is that no matter how carefully husbanded, the animals in our care at the National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute will inevitably pass away–ideally, after long and healthy lives. When a death occurs unexpectedly, the Zoo’s animal pathologists step up to determine why and how. Conservation pathologist Kali Holder shares her insights on life while working through death.

This story was first published as part of the Smithsonian Institution's Eye on Science series.

Kali Holder in her laboratory.

A Heart-Breaking Setback

In December 2023, scimitar-horned oryxes were upgraded from “extinct in the wild” to “endangered." But this huge conservation success hasn’t come easily.

These antelope-like creatures’ only hope for long-term success is if zoos such as the Smithsonian’s National Zoo selectively breed the animals and carefully reintroduce them to their native habitats in Africa. Jena the scimitar oryx was one such member of the Zoo’s breeding program.

Jena lived at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Virginia, several years ago, and when she became pregnant in 2017, the staff cheered with optimism that a brighter future for her species lay ahead. Jena’s keepers watched her closely as she brought her pregnancy to term. Everything looked good—she was healthy, there were no indications the pregnancy was in trouble—everything indicated that she would bring to term a rare calf that could help preserve the species. But during labor, Jena struggled. The calf got stuck; it wouldn’t come out. Ultimately, instead of giving birth to a healthy new calf, Jena succumbed to irreversible complications and the Zoo’s team had no choice but to humanely euthanize her.

The Smithsonian worked with the government of Chad, the Environmental Agency — Abu Dhabi and the Sahara Conservation Fund to release the scimitar-horned oryx back to their native grasslands, where they have been extinct for more than 30 years.

One of the National Zoo’s three veterinary pathologists, Kali Holder, found that Jena experienced “dystocia,” a difficult birth caused in this case by a malpositioned fetus. By studying Jena after her death, Kali learned there was nothing the oryx’s keepers could have done. “This sort of thing is almost impossible to prevent. It’s always a risk,” she told Eye on Science. “It was absolutely heartbreaking. The whole point of having these animals in our care is to make sure their population grows. You can do everything right and still fail. This is one of the hardest lessons to learn.”

“We’ll never be able to overcome the nature of nature.”

Kali keeps Jena’s cranium, complete with her three-foot long set of horns, in her office to remind her that we’re just observers of nature and we’ll never be able to control every variable. “It’s one of the cruelties in life. We’ll never be able to overcome the nature of nature,” she said.

Jena was Kali’s first big case. Since then, she’s performed biopsies and necropsies (animal autopsies) on many of the animals that have died at the National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. Her goal is to figure out as much about an animal’s body as she can. “As a conservation pathologist, I gather as much information as possible about the health of our animals—not just the cause of death (because we often know the cause of death), but I’m also going to be able to tell you everything we can glean from that last moment. How was that animal’s health over the course of its life? What was its nutritional status? Did it harbor any parasites or infectious diseases? If we find the animal carried something infectious, how might this affect animals it was in contact with, its keepers, and our collections?”

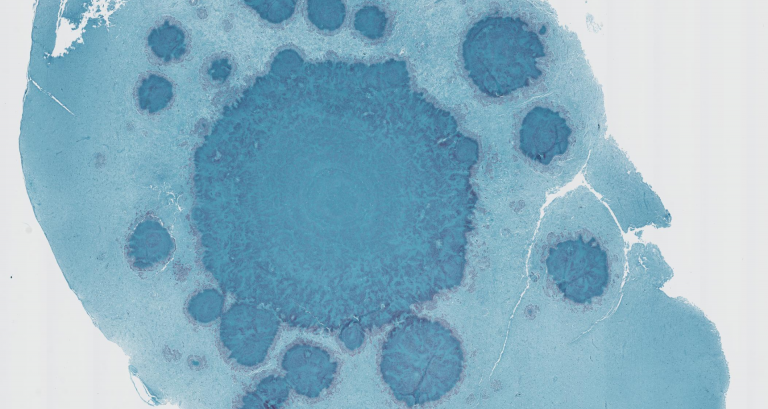

Brain section of a 2-year-old female redhead duck (Aythya americana) with progressive neurological signs (Ziehl–Neelsen acid-fast stain). These dark blue, circular to hexagonal regions are brain granulomas, similar to what a human would have in lungs with tuberculosis. Each granuloma shows a lacework of pink-purple on the dark teal background. The purple patterns are caused by large numbers of Mycobacterium sp., a type of bacterium that holds red dye during the staining process. Avian mycobacteriosis is a common cause of disease in birds, especially waterfowl. “This is a terrible disease process, but the slide is impressive whether you’re familiar with pathology or not. The large central granuloma was a stunning find on the postmortem examination, and the staining is aesthetically impactful despite the tragedy of the disease.” (Image courtesy Kali Holder)

Kali says the most important aspect of her work is how her discoveries apply well beyond the laboratory. “Knowing what species are prone to which health issues helps us figure out how to manage animal care at the Zoo and in the wild,” she said.

One would think that working with dead animals would be a heartbreaking assignment, but Kali maintains her professional composure most of the time. Cases such as Jena’s or the death of animals Kali knew in life can be difficult emotionally, but as a scientist, Kali’s focus is the challenge of gathering clues about the animal’s life.

“It’s a mystery. It’s problem solving. I’m driven by a burning curiosity to see what’s happening in my cases, and postmortem analysis is one of the ways we get to learn. I find it all fascinating, especially when I just get into the weeds. Nature is so much weirder than anything you can intentionally make up.” She says zoo pathologists are the weirdest of the animal biology nerds.

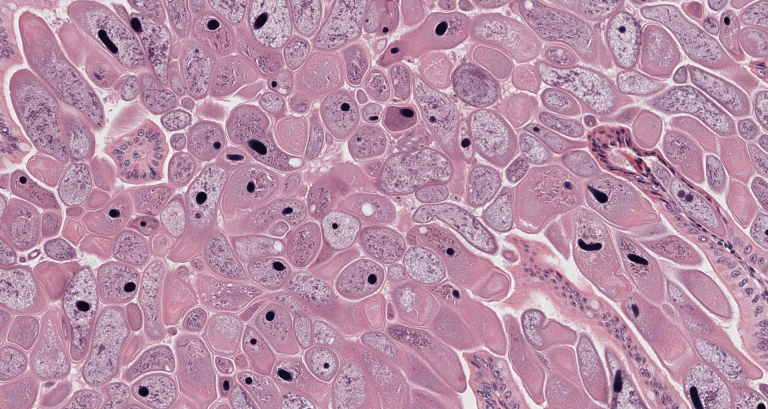

Naked mole-rat, small intestine, normal ciliates (hematoxylin and eosin stain). “Every animal in our collection has its own ecosystem. In this case, the intestine of this little rodent has a ton of protozoa packed into its gut. These single-celled organisms are normal residents of the intestinal tract in this species, and even when there are a lot of them, the tissue doesn’t treat them as an invader. A thing I love about zoological pathology is getting to learn about all the weird little particulars of so many species. My first naked mole-rat threw me for a loop, but part of the joy about my specialty is running across these idiosyncrasies and marveling at the diversity of 'normal'. Every one of us has our own ecosystem in (and on) our bodies, and for naked mole-rats it’s a mosh pit of ciliates. You do you, my wrinkly rodent pals.” (Image courtesy Kali Holder)

The Weirdest of Animal Biology Nerds

Kali doesn’t just love what she does; she also loves talking about it. She approaches her area of work—an area that might make some people uncomfortable—with professionalism, confidence, and humor. Kali once held a virtual tour of her lab…in February 2020. “I did not realize at the time how relevant some of the things I was saying—taking about animal pathogens infecting humans—were going to be for next three years,” Kali said. Pandemic or no pandemic, Kali simply feels “super motivated by outreach.” She told Eye on Science that she loves mentoring trainees. She helps run Nerd Nite DC, and she loves finding ways to connect pop culture with actual science. “What can we tell about the ecological context of made-up creatures? Where can we extrapolate real science? What do Muppets mean to the ecosystem? I like to pair the fantastic with the amazing,” she said.

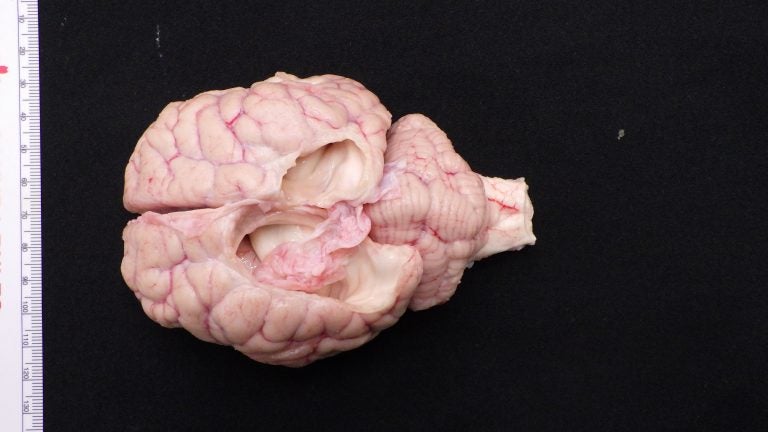

African lioness Naba came down with COVID during the pandemic. She recovered, but after six months, she showed some issues with motor coordination during chewing. Upon examination of her brain, Kali found that she was missing a whole section of her brain, including part of the motor cortex, the part of the brain responsible for movement. (Image courtesy Kali Holder)

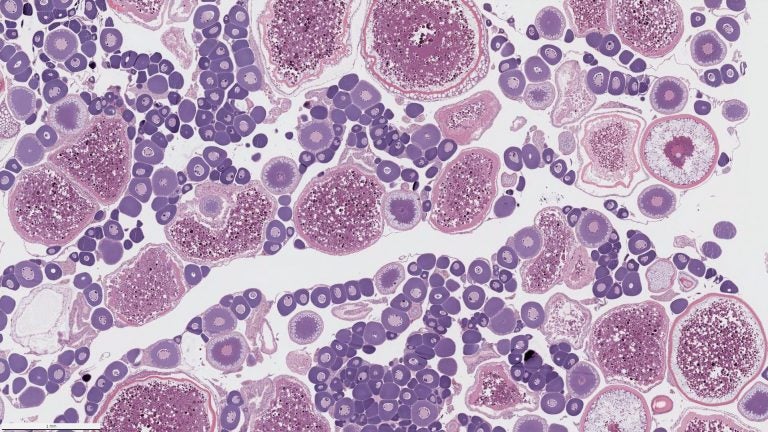

Silver dollar fish, ovary, normal (hematoxylin and eosin stain). Each of the round bodies in the image is an egg cell, and the different sizes and colors correspond to different stages of development. “I don’t have a favorite animal, but my favorite tissue is fish ovary." (Image courtesy Kali Holder)

Her outreach doesn’t stop there. Kali also participated in the 500 Queer Scientists campaign to show the world that it’s possible to be both a scientist and an openly queer woman. “One of the things I’m grateful for is that I get to provide my perspective and raise my voice and say, ‘You know what, there are scientists who are queer. It’s not going to stop you from being a scientist.’ We are out here. We are doing good work. We like to talk about our science. It’s important to show that all scientists don’t live one way. We need more voices. There are so many more ways to be human, which means there are so many ways to do science.”

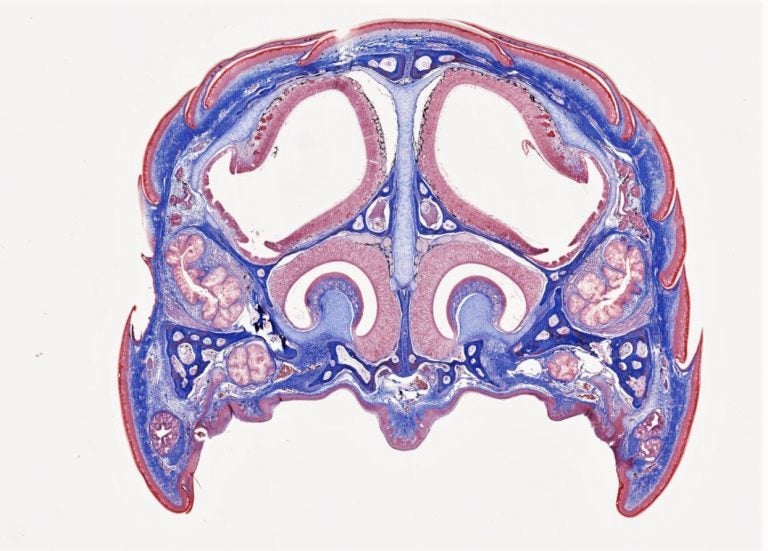

Glass lizard, head, cross-section (Masson’s trichrome stain). “Though I am primarily interacting with cases from a diagnostic standpoint, the animals themselves mean a lot to me, and the act of examining their tissues is never just about getting an answer. I appreciate the beauty preserved in these slides even when the animal is gone.” (Image courtesy Kali Holder)

Working in such a niche field has also shown Kali the breadth of talent it takes to do it right. “It takes a lot of different scientists with a lot of different specialties to do conservation. It takes people with all kinds of brains and areas of expertise to come together to do it. It’s important to keep in mind that no one of us can carry it forward and that we’re working collaboratively to make a difference.” She continued, “I don’t know anything to do with refrigerator repair but I can’t do my science without someone who knows how refrigerators work. It’s not just hard scientists here. Absolutely everyone gets credit.”

From the outside, it might be hard to imagine how someone could stay so positive and joyful while working with zoo animals that have passed on. But Kali made it all make sense. “The animal’s life has been bookended, and now it’s my job to turn that life into information so that the animal’s life continues to have an impact beyond its end. I’m trying to get as much info possible so we can apply those lessons to our care going forward.”