Kirtland's Warbler Expedition Blog

The Kirtland's warbler is an endangered migratory songbird that breeds almost exclusively in Michigan and winters primarily in the Bahamas. The species nests on the ground and will only breed in young Jack Pine forests. Decades of fire suppression prevented the formation of new breeding habitat for Kirtland's warblers, and intense nest parasitism by brown-headed cowbirds limited their reproductive success. Both factors led to population declines, and as a result, Kirtland's warblers were among the first group of species to be declared endangered in 1967.

Extensive breeding habitat management and control of cowbirds have led to a substantial recovery of the population, but despite these conservation successes, they remain one of the rarest and most range-restricted songbirds in North America.

Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center scientists study Kirtland's warblers to better understand their full annual cycle and contribute to the conservation of the species. The following is an ongoing, first-person account of their research in the field.

Summer Season Wrap-up

March 25—when our field season started in the Bahamas this year—seems like nearly a lifetime ago, but it has been another very successful season of research. I have been managing two research projects this year: a reduced cowbird trapping experiment and a new and exciting automated telemetry project. The cowbird project continues to go well. We reduced cowbird trapping even more this year and did not find a single cowbird egg in any of the 100 Kirtland’s warbler nests we located. It appears that, at least for now, cowbird trapping can be significantly reduced range-wide without putting the Kirtland’s warbler in danger. This has the potential to save the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) a considerable amount of money, time and effort, which could be invested elsewhere as we work toward ensuring the long-term sustainability of the species.

This summer and fall, we will be working closely with the USFWS to determine how best to move forward with trapping plans and to develop a long-term monitoring program, just in case cowbirds become a significant threat to the species in the future. We will also be collaborating with partners at the U.S. Forest Service and U.S. Geological Survey to model the long-term sustainability of Kirtland’s warblers under different cowbird trapping levels.

This year's new Kirtland's warbler tracking project has also gone well. After departing Cat Island, I raced to the breeding grounds to erect 11 automated telemetry towers. This array of towers was placed to maximize our ability to detect the recently radio-tagged birds from the Bahamas. After completing the tower building, we waited to see if the tagged birds would return and whether they would be detected by the towers. After a couple of frustrating weeks with no detection, we finally got our first hit, followed by many more. The first bird to return to the breeding grounds did not arrive until May 14, a bit late compared to most years. But the buzz in the birding world was that migrants all over the Midwest were late to arrive this year.

The tower array worked, and all told, we detected 38 of 63 tagged birds (60 percent) and were able to physically find and re-sight 33 of those 38 birds. This represents a real breakthrough in the study of the full annual cycle of migratory birds, which until now has been all but impossible, given the much larger breeding ranges of most birds. After re-sighting the birds, we began attempting to recapture them and find their nests. We successfully recaptured 28 of the 33 birds and found 15 of their nests. At this moment, we are deploying the last of the tags on adult warblers that have finished breeding. The post-breeding period is poorly studied in birds, and we know little about the habits of Kirtland’s warblers post-breeding to fall migration—a period of a couple months. Do they move out of Jack Pine habitat? Do they form larger, multi-family groups? Do they prospect new territories for the next year? All exciting questions we hope to have answers to over the next month or so of tracking.

Overall, we are very pleased with the efforts of this pilot season and confident that we can improve substantially on these numbers in future years, with more resources and a larger field crew. Ultimately, we will use these data to investigate how winter climate, habitat and food supply affect migration timing, migration survival and reproduction. This will in turn help us to predict how climate change is likely to affect the long-term sustainability of Kirtland’s warblers.

Departure From Cat Island

Yesterday was our last day catching and tagging Kirtland’s warblers on Cat Island. Overall, it was a great success! We caught and attached radio tags to 63 birds (58 males and five females).

The males proved fairly easy to find and catch, but the females were harder to find and less responsive to playback once we found them. We didn’t reach our goal of 100 tagged birds, but that leaves us with leftover tags to study the late-summer and early-fall movements of Kirtland’s warblers during molting and fall migration. We may also tag some brown-headed cowbirds to learn more about their movements.

A close-up of a radio tag on a male Kirtland's warbler

This past week, renowned author Scott Weidensaul and former National Geographic photographer Karine Aigner joined us on Cat Island to work on an upcoming article for Audubon magazine. We had a great time showing them around the island and telling them all about what we do. They arrived at a time when the field team was beginning to feel burned out, so their visit was a much needed injection of energy and excitement. After spending a week with Scott, it is clear that he is a masterful storyteller. I can’t wait to see the Audubon article later this fall. Karine has a keen eye, and I’m very excited to see the results of all of her hard work visually documenting our efforts.

A male Kirtland's warbler photographed just prior to release

This morning, Adrienne, Scott, Karine and I all departed on our own migrations. Scott and Karine are rushing off to their next assignment and Adrienne has more fieldwork to do in Jamaica, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. Meanwhile, I’m racing back to the breeding grounds. Our two interns this year, Steve and Chris, are staying in Cat Island for a few more weeks before joining me in Michigan. They will spend the remaining time tracking each tagged male to determine the day upon which they depart Cat Island on spring migration.

Sitting in the Nassau airport with a 5-hour layover, I’m experiencing a bit of culture shock. I haven’t seen this many people in nearly a month! There are so many foreign smells, sounds and sights in once place that it’s a bit overwhelming. I'll spend one night in D.C., and then drive the work truck to Michigan packed to the brim with solar panels, radio antennas and various tower components. On Thursday, I begin erecting 11 automated radio towers all across the breeding grounds in the Lower Peninsula of Michigan.

Typically, the first male Kirtland’s warblers begin to arrive around May 1, so it’s crucial to get these towers built and tested quickly! I’m anxiously awaiting detecting our first tagged bird in Michigan. I’m anticipating that it will be one of the most exciting moments in my career. Once we start detecting tagged birds, we will capture them to reassess body condition and remove radio tags. We will then follow these birds for the next few months, finding their nests and monitoring their reproductive success.

Once we get the towers up and running and start detecting birds, we’ll update you on our progress!Early Success on Cat Island

We are about halfway through our three-week banding period, and things are going well on Cat Island. We’ve attached radio tags to 51 Kirtland’s warblers (46 males and five females). We brought 100 tags with us and at this rate are on track to deploy about 75 to 80 of them, which we are quite happy about!

We have had good luck in both taller and shorter scrub forests, but the short scrub sites, like the one pictured below, have been the most productive.

Similar to Eleuthera, abandoned agriculture areas and goat farms have the most birds. This type of disturbance seems to keep the vegetation low and promote a lot of black torch and wilde sage, two fruiting plants that Kirtland’s love.

Along the way, we have seen a lot of great sunrises ...

... and a lot of other bird species, including North American migrants, such as ovenbirds, American redstarts, palm warblers and prairie warblers, northern parula and yellow-rumped warblers. We have also seen many Bahamian residents, including Bahama woodstar, western spindalis, bananaquits, Greater Antillean bullfinch, Bahama mockingbird, red-legged thrush and black-faced grassquits.

Today, I had a very surprising and interesting experience. I was walking quietly through the brush looking for Kirtland’s warblers when I heard a fluttering sound near my feet. I looked down to find a thick-billed vireo flapping around and struggling to fly. My first thought was that perhaps it was hurt, or maybe I was very close to a nest and the mother was pretending to have a broken wing. I stepped back to observe and noticed what looked like something attached to the vireo. Chris Fox and I moved in for a closer look and saw a giant stick insect grabbing onto the vireo. They were locked in a furious battle, and the vireo could not fly away. I was tempted to just let nature take its course but then realized that the stick insect was missing its head.

However, we could still see the insect moving its legs and grabbing onto the vireo. We cornered the vireo, and Chris was able to grab it, remove the dying stick insect and safely release the bird.

Finally, check out a slow-motion video of us releasing a Kirtland’s with his new backpack. We can’t wait to see these guys again in Michigan in a few weeks!

Adventuring in Science: Cat Island 2017

A few days ago, a team of Smithsonian scientists and interns arrived on Cat Island, Bahamas, to begin an exciting new project with Kirtland's warblers, one of North America's rarest songbirds.

This ancient schoolbook was found in an abandoned school on Cat Island. Kirtland's warblers often winter in disturbed habitats surrounding abandoned homes and buildings.

While we would love to have a much larger and more widely distributed population of this charismatic warbler, its small population size presents us with a unique opportunity. Using new radio transmitter technology, we plan to study the same individuals during both their wintering period in the Bahamas and their breeding season in Michigan. This has never before been possible in songbirds.

Our goal in the next month is to attach 100 coded radio transmitters to male and female Kirtland’s warblers. Each of these tags weighs just .35 grams and sends out a uniquely coded radio signal every 30 seconds. Our plan is to attach the radio transmitters, measure the birds, assess their body condition and then release them. After that, we’ll follow them around Cat Island using handheld radio antennas and assess how much fruit is available in each bird’s home range. Around mid-April, I will race back to the breeding grounds to build 11 automated radio towers, which will cover nearly all of the Kirtland’s small breeding range in Michigan. Two of our interns, Steve Caird and Chris Fox, will stay on Cat Island until early May and continue to follow each bird right up until they depart on spring migration, beginning in mid-April and ending in early May.

Based on our previous study of Kirltand’s warbler migration, we know that in spring, birds head straight to Florida from the Bahamas and then continue north, passing through Ohio. After departure from the island, our tagged birds will likely pass nearby automated radio telemetry towers already erected in Florida and Ohio. These towers will automatically detect them, and save the date and time that each bird passes through the tower array. As they reach their final destination in Michigan, they will be automatically detected by our newly erected tower array. Then, we can track each individual down to its breeding territory, capture it, remove the radio transmitting device and re-asses body condition. We will then follow each individual through their breeding attempts, so we can begin to understand how winter rainfall, food availability and body condition affect migration timing, migration survival and breeding success! Understanding these relationships will be important, as climate change begins to alter their Bahamian wintering grounds.

We’ve only spent a few days in the field, but we’re off to a good start with 10 radio transmitters deployed on eight males and two females! More to come soon, including photos and videos from the Bahamas.

Tracking Kirtland's Warblers

The Kirtland's warbler is an endangered migratory songbird that breeds almost exclusively in the northern lower peninsula of Michigan and winters across the Bahamian Archipelago. After dropping to fewer than 400 in the wild during 1987, breeding-season management has resulted in a population of over 4,500 today. Despite this conservation success, it remains one of the rarest and most range-restricted species in North America. Moreover, Kirtland's warblers face unprecedented threats on their Bahamian wintering grounds from global climate change. Increasing drought is expected to reduce the arthropod and fruit resources which are important food sources for wintering Kirtland's warblers. Sea-level rise is also projected to result in the loss of 11 to 60 percent of the Bahamian landmass, over the next century.

To better understand how climate change will affect Kirtland's warblers, SMBC scientists are launching an ambitious new project, which uses two methods of radio tracking technology to follow individual Kirtland's warblers from the Bahamas to Michigan. In addition to traditional radio tracking requiring biologists to actively follow individuals, this project will use an automated radio tracking tower array. Special tags that identify individual birds will communicate with the towers if the birds come within range of the array. These tower arrays are part of the MOTUS Wildlife Tracking Network, which is a system of over 300 such towers in North America.

A motus antenna by Motus Wildlife Tracking System - Bird Studies Canada

Scientists will first travel to the Bahamas to collect a variety of data about the birds and their wintering habitat. They will also attach a radio transmitter to the birds, and by tracking the birds daily movements, will be able to determine exactly when they depart the Bahamas. After departure, the birds will then be relocated on the breeding grounds by the automated radio tracking tower array in Michigan, which is being constructed for this purpose. Relocated individuals can then be studied throughout the breeding season to study their reproductive success.

This is a unique opportunity to study the same individuals during wintering and breeding, something that has never before been possible in a migratory songbird. The goal of the study is to examine how winter weather and habitat affect male and female migration timing, spring migration survival and reproductive success. Kirtland's warblers are perhaps the only migratory songbird in which this is currently possible, because their extremely limited breeding range allows one to realistically cover the entire breeding grounds with an array of radio telemetry towers.

Field work in the Bahamas is expected to begin late March, so stay tuned for updates from this exciting project.

2016 Kirtland's Warbler Winter Survey Update

March is just around the corner and that means we are getting closer and closer to another series of Kirtland's warbler surveys on the wintering grounds.

Kirtland's warbler with geolocator on its back.

As you may remember from previous blog posts, Kirtland's warblers spend the winter primarily in the Bahamas, especially on the central islands (Eleuthera, San Salvador, Cat Island and Long Island). However, recent evidence from our geolocator study indicates that perhaps as much as 15 percent of the population winters in the extreme eastern Bahamas or on Turks and Caicos.

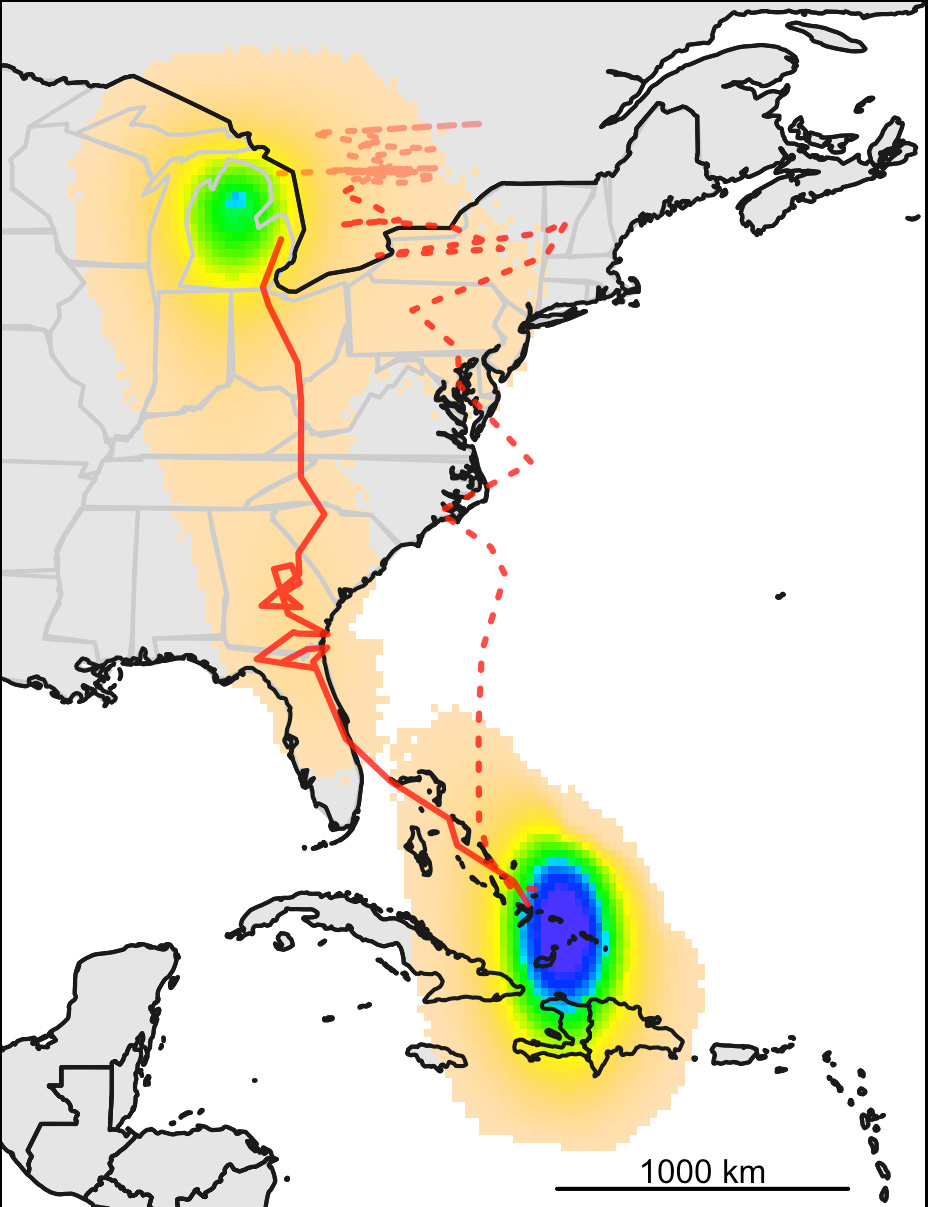

Figure 1 (below) shows the migratory path of one male Kirtland's warbler, from his breeding grounds in northern Michigan to his wintering grounds.

Figure 1. Relative probability of residency for one male Kirtland's warbler. Beige indicates the least time spent, while blue indicates the most time spent relative to the full year.

Solid red line = spring migration. Dashed red line = fall migration.

Light-level geolocators collect information about the intensity of light to determine the time of sunrise and sunset. Because sunrise and sunset times vary depending on one's location on the planet, we can then use this information to infer latitude and longitude throughout the year. While incredibly useful, this type of data is noisy and can only pinpoint locations to within approximately 200 kilometers (120 miles).

As a result, this male could have wintered anywhere in the eastern part of the Bahama Archipelago, with the most likely islands found within the blue oval (Figure 1). This particular male had one of the longest spring migrations of all the males we tracked, flying more than 3000 kilometers (about 1800 miles) in just 16 days.

There are a few sightings of Kirtland's warblers from Turks and Caicos, but no formal surveys have been conducted there. Joe Wunderle, one of our wintering Kirtland's warbler experts, actually saw his first Kirtland's warbler on North Caicos, well before he knew he would spend much of his career working with these birds. Because so many birds appear to be wintering in this region, we have planned a trip to Turks and Caicos to carry out surveys.

The team consists of long-time Kirtland's warbler researchers Dave Ewert of The Nature Conservancy and Joe Wunderle of the U.S. Forest Service, as well as Scott Johnson, a colleague from the Bahamian National Trust, and myself.

We will spend two weeks in late March and early April surveying for Kirtland's warblers in any good-looking habitat we can find there. We hope it will be a productive trip and that we will find a lot of Kirtland's warblers. I'm sure we will spot a lot of other interesting wildlife along the way.

Look for an update on these surveys sometime in late March or early April!

Kirtland's Update

As we near the close of our summer field season with Kirtland's warblers, we have had some very exciting developments regarding both geolocator and cowbird studies.

In terms of the cowbird study, our crew has had an absolutely fantastic year, finding 150 Kirtland's nests. Last year, we only managed to find 57 nests, albeit with fewer people. In a typical year, all Kirtland's warbler nests have a cowbird trap within 1.6 kilometers (1 mile), but as part of our trapping reduction experiment, we now have nests more than 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) from the nearest trap. However, we have not found a single cowbird egg this year! This result holds a lot of promise for the future in terms of reducing the conservation-reliance of the Kirtland's warbler. It will be very interesting to see if this trend continues next year or if the effects of the trapping reduction perhaps take time to build up.

Our geolocator recapturing effort is also going quite well. We have recaptured 26 of 60 birds that had geolocators attached last year. One geolocator fell off, two didn't work, two batteries died (but should have recoverable data) and the other 21 collected a full year's worth of data. However, our most recent recapture was certainly the most exciting.

Katie Koch, migratory bird biologist at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, found one of our geolocated birds in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, just southwest of Marquette. Roughly 35 male Kirtland's warblers reside in the Upper Peninsula each year, but the one that she found was banded last year near Grayling, about 322 kilometers (200 miles) away as the crow, or Kirtland's warbler, flies.

While dispersal distances from birth site to first breeding site (i.e., natal dispersal) this large are probably not uncommon, dispersing between two consecutive breeding sites (i.e., breeding dispersal) this far may be quite rare. It was an exciting find but meant a long 5-hour drive up to Marquette. Fortunately, it only took about 10 minutes for us to re-locate and capture this bird. The data downloaded right away, and I'm anxious to analyze it to see if the bird's movements were unusual in any other way.

Photo by Jeff Koch

I'll be travelling to Oklahoma at the end of July to learn the latest techniques necessary to analyze these data. Stay tuned for one final update late this summer when I should be able to show you a few maps of where our geolocated Kirtland's warblers went last winter!

Welcome to Kirtlandia

With about two weeks of fieldwork under our belts, the 2015 Kirtland's warbler field season has officially begun. For those of you that followed along last year, you know this is an exciting time for us. Last year, I attached 60 light-level geolocators to male Kirtland's warblers across the breeding range in northern Michigan. The devices are looped around the birds' legs and sit right in the middle of their backs (see image below — note the small light sensor sticking out).

These geolocators have small sensors that measure light intensity every two minutes, 24 hours a day. These data are stored on the device, which necessitates that we re-capture each individual a year later to download the data. From the light levels, we can estimate day length and solar noon, which in turn give us latitude and longitude, respectively. From a broader perspective, the geolocators will tell us a great deal about where Kirtland's spend their winters, migration routes, and migration speed and timing — all information that is currently lacking.

Photo by Nora Diggs

Last week, we began heading out into the pine barrens of northern Michigan to find the birds carrying geolocators. We then used playback and mist nets to recapture them. So far, we've recovered 23 birds with geolocators. One geolocator fell off, and two devices didn't work. However, we have 20 with usable data and are far ahead of schedule!

In addition to recovering the geolocators, we have some other new and exciting work going on this year with Kirtland's warblers. First, a little background:

In 1971, there were only 200 male Kirtland's warblers left in the world. As a result, they were one of the first species declared federally endangered. Brown-headed cowbirds were quickly determined to be one of the likely causes of the Kirtland's warbler decline. Cowbirds are generalist brood parasites, which means they lay their eggs in the nests of many (more than 200) other species of birds. The "host" birds will often raise the nestlings to the detriment of their own young. In 1971, nearly 70 percent of all Kirtland's nests were parasitized by cowbirds.

As a result, Kirtland's warbler pairs were only raising, on average, one nestling per pair. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) quickly took action and began trapping cowbirds across the breeding range. Within a year, nest parasitism had dropped to 6 percent, and it has continued to drop to about 1 percent in recent years. Despite this timely management action, the Kirtland's population did not rebound for another 20 years. Around that time, a large fire broke out in Michigan and naturally created a lot of new jack pine habitat. Once that happened, Kirtland's warbler populations exploded, with more than 2,000 males existing today.

Cowbird management clearly played a crucial role in the recovery of the population, but it is very expensive. Moreover, now that the Kirtland's population is much larger, it may not be as necessary as it once was. After all, cowbirds are a natural part of the ecosystem, and many other avian populations experience fairly high rates of parasitism but still manage to sustain themselves.

Given these two facts, the FWS sought to re-assess the cowbird-trapping program. To assist them in this goal, I proposed a large-scale trapping reduction experiment to determine whether Kirtland's warblers can remain sustainable under a reduced trapping regime. Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center scientist Pete Marra and I recently received a grant to carry out this work over the next two breeding seasons.

Cowbird trapping began April 15, but about 11 of the 57 traps remained closed. We will be busy this summer finding a lot of nests at various distances from the nearest trap to determine how parasitism rates vary in relation to trap distance. We will also be carrying out cowbird surveys across these same sites and radio-tracking a few cowbirds. Together, this will help us determine the effective range of a single trap, and ultimately help the FWS re-design the cowbird-trapping program to reduce costs, all the while still protecting the Kirtland's warbler population.

We've got a ton of work ahead of us, but this year's team is ready to go. Stay tuned for more updates as the season progresses!

Success on Cat Island

After striking out time and time again on Abaco, we've had some major successes on Cat Island. Within just a few minutes of starting our very first transect, we found a Kirtland's Warbler!

Photo by Ashley Hannah

As we walked down the road broadcasting a variety of song and call notes of the Kirtland's, we heard some loud call notes coming from the vegetation on the east side of the road and out pops a nice bright adult male! Little did we know that this was the first of many more to come.

We've now completed seven days of transects and found a total of 47 Kirtland's Warblers on the island. Joe and Dave have never found so many before on one island in such a short time. Given the vast amounts of habitat that we couldn't access it's quite likely that Cat Island alone holds more than 10 or 20% of the wintering Kirtland's population.

While we enjoyed seeing all of the birds, one was more special than the rest. Ashley and Dave were walking along one of their surveys and attracted a young male with color bands. They noted the color combination and after exchanging a few emails later in the day, it turned out that this particular male was banded in Wisconsin as a nestling last summer. The odds of finding this bird were incredible! Talk about a needle in a haystack.

Along our transect routes we saw lots of other interesting things, including a large tarantula (pictured below). These spiders are among the ones hunted by tarantula hawks, a type of wasp. These wasps sting and paralyze the tarantula, transport it to a burrow, and lay eggs on the spider. Then the larvae develop and feast on the living, but paralyzed, tarantula! The tarantula was not moving and may have been recently stung by one of the many tarantula hawks we saw in the area.

Photo by Nathan Cooper

We also saw quite a few golden silk orb weavers (pictured below), a brown racer (a type of snake), thousands of land crabs, and at least 46 species of birds.

Photo by Nathan Cooper

Now we are all headed back to our various homes with lots of data in hand. Over the coming months, we'll work on analyzing these data and determining what conclusions we can draw.

The 2015 Kirtland's Team. From left to right: Dave Ewert, Genie Fleming, Ashley Hannah, Nathan Cooper, Joe Wunderle.

In early May I head back to northern Michigan to start the first year of a two-year cowbird trapping experiment. Stay tuned over the next month to learn more about this exciting project.

Abaco Summary

This past Friday, April 3, we finished our last survey on Abaco. During our 23-day stay we completed 29 surveys in coppice habitat, 31 in pine habitat, and 35 in mixed coppice-pine habitat. Our transects were spread across the entire island, with each lasting about 48 minutes, for a total of about 80 hours of survey time. In that time we only found four Kirtland's warblers, and all in coppice habitat on the southern tip of the island.

Kirtland's have been reported on Abaco and some of the other Pine Islands in the past. We visited some of the previous observation sites and the habitat often looked right. However, one thing we noticed is that many of these observations were in the early Fall or late Spring, when Kirtland's are migrating, so it appears that some of the observations were just of birds passing through.

Another complicating factor is misidentification. To an untrained eye, Kirtland's look a bit like the Bahamas warbler. The Bahamas warbler spends all of its time in pine habitats foraging right on the trunks of pine trees, and we suspect that some of the sightings in pine habitat may just have been Bahamas warblers, a species found only on Grand Bahama and Abaco.

While collecting these data wasn't always the most exciting time, it was incredibly valuable nonetheless. We are now pretty certain that Kirtland's warblers do not prefer pine habitat or perhaps the more northern pine-dominated islands in general.

Our initial impression is that the pine habitats just don't have enough of the fruit plants (e.g., wild sage, black torch) that Kirtland's love to eat in the winter, nor the dense understory they prefer to forage in. Ultimately, our work will help the Bahamian government and conservation organizations protect wintering habitat by allowing them to focus their efforts solely on coppice habitat and on the more central islands.

Our team has identified several different opportunities for protecting more wintering habitat in the Bahamas. Large-scale preserves are always one option, and when coupled with eco-tourism, this might be economically viable in some areas. One of the other potential opportunities for creating more Kirtland's habitat is through goat farming. It turns out that goat grazing provides the right type of disturbance to favor growth of wild sage and black torch. On Eleuthera, we've found quite a few Kirtland's on goat farms.

We've also seen Kirtland's underneath power lines. Thus, power line corridors, which have to be routinely mowed, allowing re-growth of wild sage and black torch, are another potential opportunity that we are pursuing.

While walking for hours through the various pine and coppice habitat on Abaco, we saw lots of birds—about 75 different species of both resident and migratory birds. We also saw lots of other interesting critters, including raccoons and wild pigs, silver argiope spiders, starfish, spotted eagle rays, green sea turtles, dragonflies, and many friendly Bahamian dogs.

Saturday we moved to Cat Island. The airport was enormous and we got lost a few times, but that and our other adventures on Cat Island will have to wait until next time…

Cat Island airport. Photo by Nathan W. Cooper.

Greetings from Abaco!

Greetings from Abaco! After a long winter of data analysis and grant writing I'm finally back in the field.

Our team consists of Joe Wunderle (Research Wildlife Biologist—USFS), Dave Ewert (Senior Conservation Scientist—The Nature Conservancy), Genie Fleming (Field Director—Puerto Rican Conservation Foundation), Ashley Hannah (Field Assistant), and me, Nathan Cooper (Postdoctoral Researcher—Migratory Bird Center). Dave and Joe are long-time Kirtland's researchers, Genie is our expert on Bahamaian plants, Ashley has worked with Kirtland's Warblers in Wisconsin, and if you remember from past blog posts, I spent all of last summer working with Kirtland's on their Michigan breeding grounds.

Our mission while we are in the Bahamas is twofold. First, we want to find more wintering locations for Kirtland's Warblers to add to the evergrowing database. Second, we want to test an important habitat preference.

First, a little background. Kirtland's Warblers are thought to winter almost exclusively in The Bahamas, though there have been a few sightings in Cuba, Bermuda, and on Hispaniola. In 1998, Christopher Haney and colleagues, compiled reported records all the way back to 1841 and strongly suggested that Caribbean Pine habitats are the important habitat for the Kirtland's Warbler. Caribbean Pine is found on the more northern Bahamian islands of Abaco, Andros, and Grand Bahama, and very sparingly on the Turks and Caicos.

However, Joe and Dave's searches on the non-pine islands of Eleuthera, San Salvador, and Long Island have proven to be very successful. On these islands, Kirtland's occupy coppice, a relatively short-statured, dense, and scrubby broadleaf habitat. Because the results of these more recent searches have not matched well with the pine habitat paradigm, we designed a study to formally test the pine vs. coppice habitat preference.

We arrived to Abaco last week and have begun our work. We've completed about 30 transects (see picture below), using playback of the warbler's song and call notes. So far we've run transects in a variety of coppice, pine, and mixed coppice/pine habitats around the southern portion of the island. We've seen lots of interesting birds along the way.

Highlights include:

- Bahama Warblers,

- Bahama Woodstars,

- Cuban Emeralds,

- Loggerhead Kingbirds,

- Bahama Swallows, and

- Rose-throated (formerly Cuban) Parrots.

We also found four Kirtland's Warblers, and all in coppice habitat, so far. We've got about two weeks left here on Abaco and we'll post another update when we have completed our surveys. Then we move south to Cat Island…

Kirtland's Warbler winter habitat on Abaco Island in the Bahamas. Photo by Nathan Cooper.

Kirtland's Warbler Study

Our summer field season is quickly winding its way to a close. Tom and I spent the last month and a half furiously attaching radio transmitters to 7-day-old nestlings. Radio transmitters are small devices (0.5 gram in our case) that emit a regular short-range pulse that can be detected using directional antennae.

1-day old Kirtland's Warbler nestlings with infertile egg.

Each device transmits at a slightly different frequency so we can keep track of who is who. We attach them on day 7 because they are big enough to handle it, but not so old that they are likely to prematurely leave the nest if disturbed.

7-day old nestling with radio transmitter attached.

We attach transmitters to figure out:

- basic survival rates during the post-fledging period

- whether fledglings use habitat types other than their breeding habitat.

Fledglings of many species have recently been found to move out of their breeding habitat into nearby and often early-successional forests that presumably provide better ground cover and/or more abundant food resources.

Fledgling with radio transmitter several days after leaving the nest.

To attach the device we use the same leg-loop harness that we used for the geolocators. However, we used a thinner and more elastic material to accommodate growth and allow the devices to naturally fall off later in the year. Once we get the device attached, we wait patiently for those nestlings to grow big enough to leave the nest; usually on day 12 or 13 after hatching.

Nathan Cooper attaching radio transmitter to 7-day old Kirtland's Warbler fledgling

We've used up our stock of transmitters for the year, tagging about 70 birds. At one site, we found high levels of nest predation during the last part of the nestling stage. Some of the nestlings were killed and then buried 4 inches to 5 inches under the ground, apparently something that free-ranging pet cats are known to do. Cats are a huge threat to small birds and other wildlife so keep those cats indoors!

Most of our nestlings survived long enough to make it out of the nest. Once young birds leave the nest they are called fledglings. Kirtland's Warbler fledglings are almost completely helpless when they leave the nest, and are typically not able to do much more than clumsily hop around on the ground. Luckily, their plumage is well camouflaged for their environment and they are really good at sitting perfectly still and being quiet.

After a day or two spent hopping around on the ground, Kirtland's Warblers manage to get up into the low branches of the Jack Pines where they will spend much of their lives. Flight abilities are weak at this point. They can make it from tree to tree, although with little control. It's best described as a somewhat controlled crash landing. The parents are very defensive at this point and will often pretend to have broken wings, fluttering around in the undergrowth and making lots of noise to draw attention away from their precious young.

Adult male Kirtland's Warbler defending nestling during the banding process. Note when he pretends to have broken wing when he lands on the scale.

If that doesn't work they will aggressively attack any human or non-human intruders. Tom and I had more than a few adults land on our backs or the antenna as they engage in attack maneuvers.

Predation rates during the first few days out of the nest have been fairly high. But it appears that if birds can make it past this period, they have a pretty good chance of making it to independence. Causes of death are somewhat unclear. We haven't seen any evidence of starvation. But this isn't too surprising because it has been a great year for insects and blueberries, both of which Kirtland's love to eat. It's quite difficult to tell what type of animal killed a fledgling even with the carcass in hand, but we certainly suspect that small mammals and some avian predators such as hawks have been involved.

Dead fledgling found buried 4-5 inches underground.

We have seen a few of our fledglings move into much older stands of Jack Pine, but for the most part, birds have remained within 600 meters to 900 meters of the nest in the same habitat they were born. Over the next year, we will more carefully analyze these movements and try to determine whether young (6-7 year) or older (9-12 year) Jack Pine stands provide equally good habitat for fledgling survival.

The batteries on the transmitters only last about 35 days and that matches up well within when the fledglings become independent from their parents. As of today, we only have 3 fledglings with active transmitters. Once those batteries die, we are officially done for the season.

Stay tuned throughout the winter as we will be traveling to three islands in the Bahamas (Cat Island, Abaco, and San Salvador) and Cuba to help reveal a fuller picture of the Kirtland's Warbler wintering range.

Also, don't forget to check back next spring as we begin to re-capture adults returning with geolocators. These devices will provide us with fairly accurate data on wintering location and both spring and fall migration routes.

Kirtland's Warbler Study

Ecology is a beautiful thing. Organismal interactions are multifaceted to a degree very few, if any, of us can fully understand. Luckily, some are simple and interesting enough that even an intern can write about them during rain delays from fieldwork. Most folks that know anything about Kirtland's warblers know first about their strong dependence on Jack Pine trees. The next ecologically-relevant factoid most recollect is their battle against the dreaded cowbirds. Since we study birds here, and not trees, I'm opting to write about the latter.

Brown-headed cowbirds are nest parasites—they lay their eggs in the nests of other birds. While this behavior isn't unique among North American birds, cowbirds are our only obligate nest parasites. They never make their own nests and are entirely dependent upon other birds to provide parental care to their young.

Some ducks, coots, and others are facultative nest parasites, making nests of their own to go along with the eggs they slip into the nests of neighbors. It's an odd behavior, but perfectly reasonable viewed through the lens of natural selection. If you evolved to make use of grubs kicked up by buffalo and had to fly miles back to your nest every few minutes to keep your kids happy, you'd hire a nanny too.

You may notice a problem here. There are no bison in Michigan and bison don't use Jack Pine forests. Well, we humans have a special knack for redecorating our surroundings at the behest of our neighbors. The expansion of agriculture on this continent by European settlers brought the cowbirds knocking at the Kirtland's warblers' doors.

A healthy majority of nests were parasitized by cowbirds in the 1960s. A cowbird egg takes 12 days to hatch while a Kirtland's egg takes 14. If the baby Kirtland's warblers still manage to hatch, they're at an extreme disadvantage having to compete with the much bigger cowbird nestlings for food. Coupled with the lack of forest fires creating room for fresh Jack Pine habitat, this drove the Kirtland's warblers to near extinction. So, what was the solution?

In order to restore the Kirtland's back to safe levels, the cowbirds had to be removed, and that is accomplished with cowbird traps. How does one trap a cowbird? Well, If you put 5 or 6 male and female cowbirds in a cage, give them food and water, and let them sing, other cowbirds join the party. If you adjust the openings in the top of the cage so that they're big enough for a cowbird to squeeze through, the cowbirds fall in and have a lot more trouble finding their way out. At the very least, the new cowbirds stick around long enough for someone to check a trap each day and remove them. Basically, we use their own kind to lure them in and keep them away from our warblers.

A few thousand cowbirds are removed each year, and while that may seem like a lot, I can assure you cowbirds are doing just fine. Working with vireos last year in Massachusetts, I ran into my fair share of cowbirds, but I didn't exactly bump into many (any) Kirtland's warblers. The good news is, through roughly 50 nests we've found this year, we haven't bumped into a single cowbird egg yet.

It's easy to view this as a triumph of wildlife management and conservation, and, by all means, it certainly is, but it is important to remember how we got here—we opened the door for the cowbirds to wreak havoc. Kirtland's warblers may be off the proverbial cliff hanging over extinction, but we had to put a lot of work into saving these birds. Cowbirds are just doing what any species would presented with a fitness-oriented opportunity. To view them as the bad guy, is a tad misguided. We'd do to make sure that the wonderful players in the game of ecology, molded by generations that evolved over thousands of years, don't disappear in a flash.

On the next episode…How to radio track a fledgling and look like you're contacting aliens at the same time. Stay tuned.

Kirtland's Warbler Study

All things Kirtland's Warbler related are going great up here in northern Michigan. We have now successfully attached 60 geolocators. For those just joining us, a quick reminder about how they work.

Light-level geolocators are small (0.5 gram, less than a paperclip) devices that collect data about ambient light levels. From this, we can determine sunrise and sunset, and then during most of the year, we can infer latitude and longitude within about 100 km. This allows us to track birds like the Kirtland's that are still too small to carry heavier satellite and GPS based devices.

We deployed geolocators across nearly a 100-mile latitudinal gradient, which represents all of the Kirtland's habitat in the lower peninsula of Michigan. Now we just have to wait and see how many we can re-capture next year. Once we re-capture the males and download the light-level data we can begin to understand whether the population all goes to the same general area or spreads out across much of the Bahamas or other places in the Caribbean.

We will also get some important information regarding migration routes and timing for both spring and fall migration. This will be the first such data collected on Kirtland's Warblers, outside of a small pilot study a couple of years ago.

Now that the geolocator part of the study is essentially finished up for this season, we have diverted nearly all of our effort to nest searching. One of my first field jobs as an undergraduate was in Washington State, out on the Olympic Peninsula. It was a beautiful location with lots of cool birds, but I really struggled at nest searching and found it incredibly frustrating. I ended up spending much of my time in the following years either working with Eastern Kingbirds, which have very easy to find nests, or with wintering birds, which aren't breeding at all. As a result, I was a bit intimidated about finding Kirtland's Warbler nests.

However, over the last few weeks of nest searching I have found that I really enjoy it. Kirtland's Warblers nest right on the ground in the thick vegetation often found under the endless rows of small Jack Pines. The nests are quite well hidden and therefore you can't just go around looking for them. Instead, you have to carefully observe the male and female for nesting behavior.

The process first begins during site selection. The males and females will often forage closely together during this period, occasionally dropping down to the ground to check out different possible nest sites. The female will rub around certain areas, trying to find the perfect spot. Once she's found a good spot, she'll begin to gather nesting material. Large pieces of grass, pine needles, and various other bits of vegetation are all collected in 10 minute or so bouts and then taken back to the nest.

The male doesn't help build the nest at all in this species and instead spends his time patrolling the territory and keeping out intruders. During nest-building females are almost completely silent and pretty secretive. Following them can be a real challenge.

If you get too close they fly away or become anxious and won't visit the nest. And if you're too far, you lose them in the dense vegetation. We found a few nests during the 5-6 days that it takes females to build a nest, but mostly we've found them during the incubation phase or nestling phase. During incubation, the female spends about 40-50 minutes of every hour on the nest keeping the eggs warm. She only comes off to feed about once per hour, but luckily the male is willing to help out during this phase.

He forages around the territory, stopping to fight with any intruding males, and singing the whole time. Then as he approaches the nest, his song gets quieter and a bit muffled (since he has so much food in his bill). He typically starts looking around anxiously, presumably making sure no nest predators like Blue Jays are watching.

They often seem to notice us during this time as well, and we've found that lying on the ground and hiding behind trees is often necessary. If not too disturbed, the male then quickly dives down to the nest and feeds the female. For trickier males, it has taken up to two or even three hours of observation for us to find nests during this period.

After 13-14 days of incubation the eggs hatch and the nestlings need to be fed and kept warm. The female often sits on the nestlings, while the male forages and brings food back. As the nestlings get older and approach fledging date on day 9 to 11, the female spends more and more time away from the nest looking for food to feed those hungry nestlings.

All in all it's an exciting time here in Michigan. The nestlings are just beginning to leave the nest and we have just started to put small radio transmitters on them in order to track fledgling survival. More about this (including some video of the attachment process) in a couple of weeks. Next week Tom will write about nesting from a broader perspective and introduce the perils of nesting near populations of the Brown-headed Cowbird.

Kirtland's Warbler Study

Just over two weeks are in the books here in northern Michigan, and a lot has gone on in such a short period of time. The females were just rolling into town during our first day in the field, but we heard plenty of males singing right from the start. Females of migratory species usually arrive after the males, enabling them to judge potential mates on habitat-related qualities, such as the size and quality of the territory they're defending.

As the season has progressed we've seen more and more female birds and have shifted our focus toward determining if they are building a nest. Having seen a few females with nest materials in their bills through the end of May, we finally got a major monkey off our backs on the first day of June—finding our first nest of the year.

The morning was winding down and Nathan wanted to double-check a pair sitting on a territory right next to our truck before we called it a day. He had seen the female looking "anxious" earlier in the morning and was convinced he was near her nest. Before I could double-back to assist for a second look, he had already tracked our girl placing some dried up grass and needles under a small Jack pine. A few steps farther back and using another pine as cover, Nathan struck the perfect balance between standing close enough to track the bird and standing far enough away to give her the security to go about her business building a home for her future young.

Drawing back the curtain of freshly-leaved shrubs revealed a small, brown cup made up of interwoven twigs, needles, and grasses, and built into the side of a small depression that enveloped the base of a young pine. After tracking a dozen or so females carrying nesting material without finding a nest at the end of the rainbow, we were ecstatic to finally find nest #1, or NWC01 as it will be known henceforth.

With hopes of finding many more, this was an important first step in understanding the behaviors indicative of a female close to her nest. Unlike their male partners, the females tend to stay low to the ground and rarely make a noise beyond their sharp, singular call note. We'll take every edge we can get in learning how to track these elusive birds through the thick plantations of Jack pine.

Much to our delight, the Kirtland's warbler isn't the only species setting up shop amongst the rows of Jack pine. As is often the case, setting aside a large chunk of land with the intention of conserving a particular species of interest has the added benefit of placing other species under the same protective umbrella.

Nashville Warblers and Palm Warblers are the main warblers sharing the expanses of Jack pine with the Kirtland's, and Ovenbirds and Yellow-rumped Warblers are often heard from the adjacent, taller stands of pine that have outgrown Kirtland's warbler suitability.

A plethora of sparrows are fairly easy to find, including Eastern Towhees, Dark-eyed Juncos, Chipping Sparrows, Grasshopper Sparrows, Clay-colored Sparrows, Field Sparrows and Lincoln's Sparrows. We've stumbled upon a Common Nighthawk and a Northern Harrier roosting in a couple of more open areas. Blue Jays and Brown Thrashers seem as abundant as ants, and Upland Sandpipers are scattered throughout the clear-cut fields being prepared for future plantings.

The coming days will hopefully bring many more nests and the first attachings of geolocators. Stay tuned.

Kirtland's Warbler Study

I wanted to take this chance to introduce everyone to a new project at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center (SMBC) dealing with an exciting endangered species. For those of you that don't know, the Kirtland's Warbler is a small bird that breeds in Jack Pine forests in Michigan and winters in The Bahamas, and possibly other parts of the Caribbean as well.

In the 1970's there were less than 200 Kirtland's Warblers anywhere in the world. Through extensive habitat management on the breeding grounds and control of Brown-headed Cowbirds (an important nest parasite) the population has increased to over 2,000 singing males. It is a true conservation success story, but populations have not totally recovered and current and future threats to their populations still exist.

Kirtland's Warbler breeding habitat.

Pete Marra, director of the SMBC, and I recently received funding to study several aspects of the Kirtland's Warbler annual cycle that we know little about. First, we will be using light-level geolocators, which are small tracking devices that can infer latitude and longitude from ambient light levels, to track Kirtland's Warblers over the next year. These devices will allow us to gain a better understanding of where these birds migrate to during the winter.

Preliminary data suggest that some birds may spend the winter in Cuba and the SMBC is planning a trip there later this winter to look for them. Second, we will be using small radio-tracking devices to follow young birds for the first month out of the nest to better understand their survival rates and habitat use during the critical post-fledgling period. This research will hopefully help the Kirtland's Warbler Recovery Team in their conservation efforts.

Over this summer we'll update you every once in awhile to let you know how things are going in the field and keep you up to date on any exciting happenings. First, a brief introduction of our team. I'm Nathan Cooper and will be leading the team in the field. I recently finished up my Ph.D. at Tulane University and the SMBC.

A few months ago, I hired Tom Ryan, a recent SUNY ESF graduate, to help out with fieldwork this summer. Tom has a real passion for birds and is excited about using experience gained this summer to begin his own career in Ornithology. We are also lucky enough to have David Bryden volunteer on the project in June.

David will join us from New Zealand, where he has been helping reintroduce another endangered species, the Kakapo. Check out their amazing story, too.

Together, we are looking forward to a great season in northern Michigan. Check back soon for more updates as we begin our field season this week!