How to Care for Cuban Crocodiles

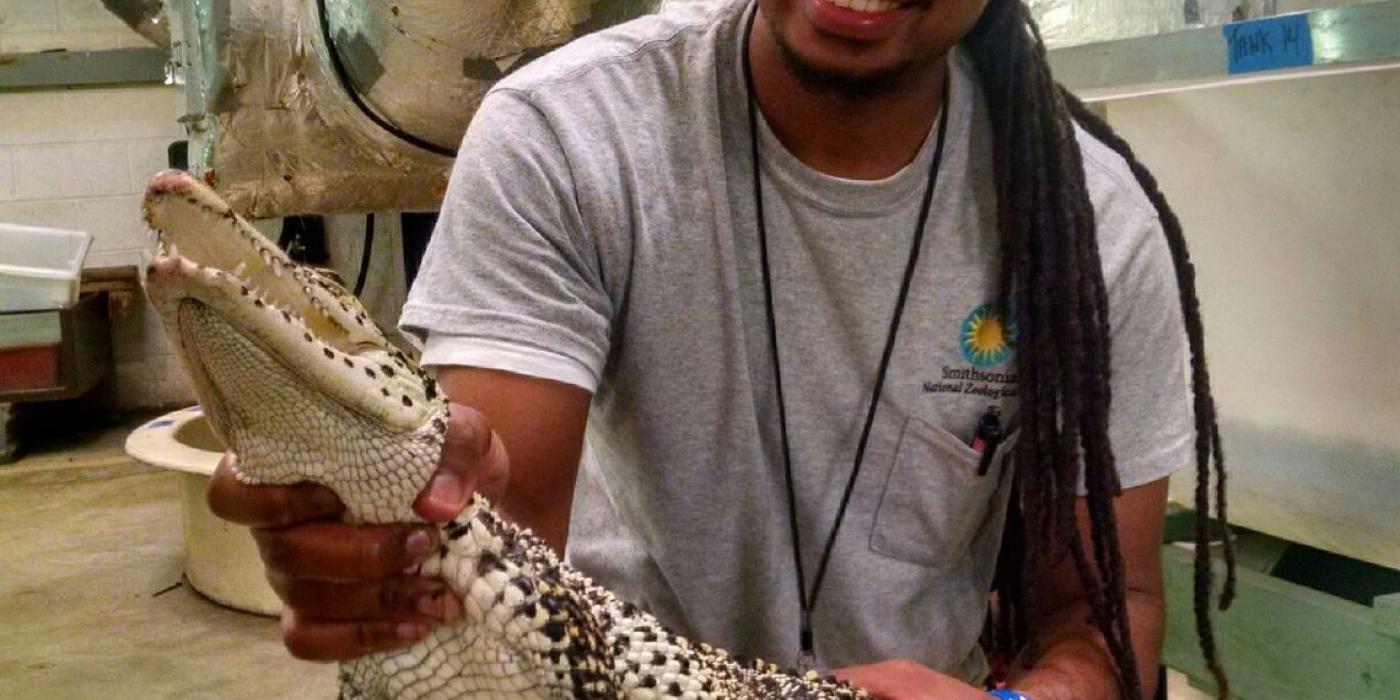

Jump into animal keeper Kyle Miller's experiences caring for Cuban crocodiles. Kyle works in the Reptile Discovery Center with a variety of animals — from snakes, iguanas and turtles to four crocodilian species: the Indian gharial, Philippine crocodile, American alligator and, of course, the Cuban crocodile!

As a kid, I was into dinosaurs. Reptiles, birds and invertebrates were fascinating to me, since many are like dinosaurs. Crocodiles were my favorite. Getting to work with these big, smart, aggressive crocodilians every day has been a dream come true for me.

A big part of my job is actively participating in Cuban crocodile research programs both here at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and in Cuba, where these animals come from. I co-founded an annual program in collaboration with colleagues from other zoos, including the Zapata Crocodile Farm in Cuba. We meet in Cuba every year to conduct a health screening and evaluation on the Cuban crocodiles at the Farm. Being able to participate in this program has helped me learn a lot about Cuban crocodiles in their native range.

Right now, Cuban crocodiles are only found in two swamps in Cuba: the Zapata Swamp and the Lanier Swamp. American crocodiles are outcompeting and breeding with the remaining wild Cuban crocodiles. When the two species of crocodilians breed, they create a hybrid species.

Cuban crocodiles are already critically endangered and the continued hybridization is lowering the population of pure crocodiles. One day, the only pure Cuban crocodiles left in the world may be in human care. Today, we are doing what we can to preserve what’s left of pure Cuban crocodiles and create a sustainable population.

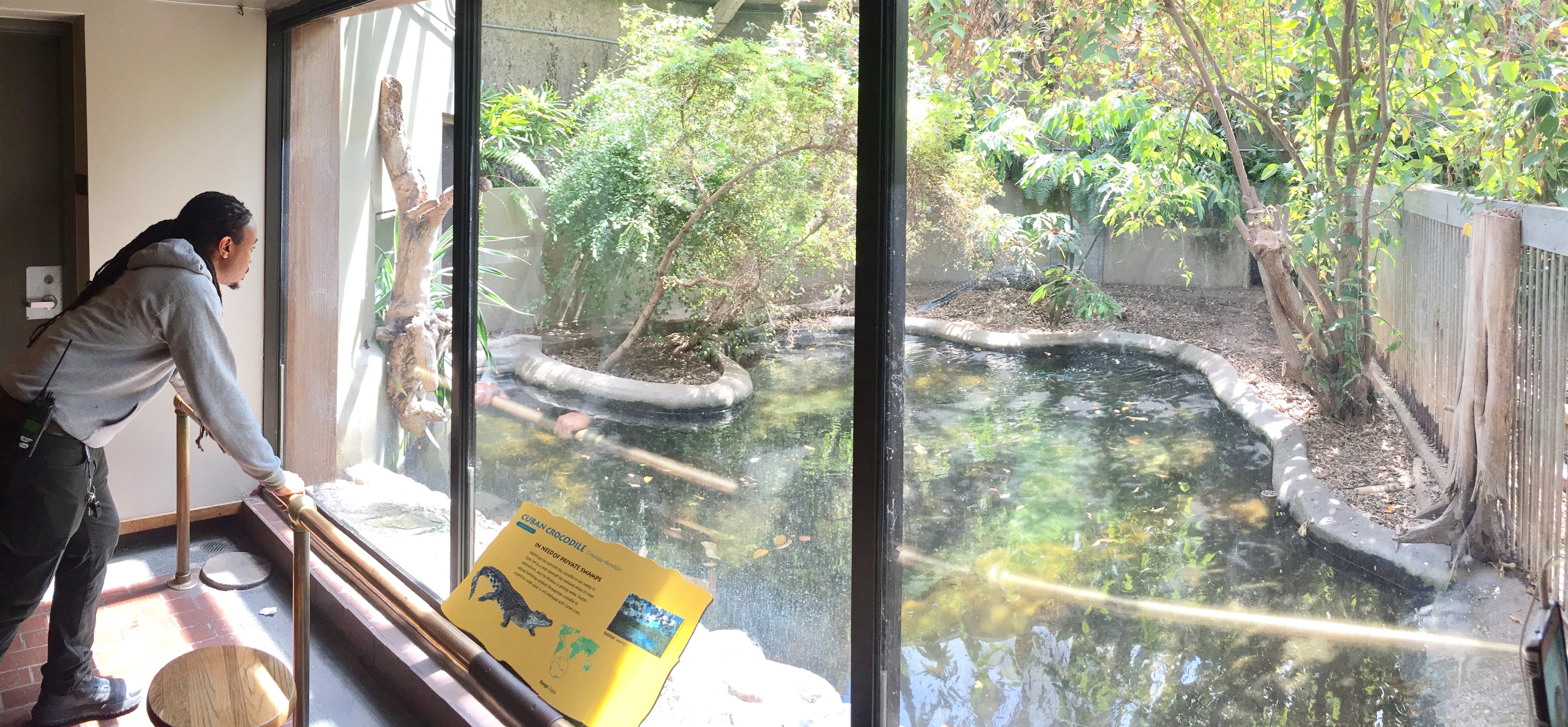

Here at the Reptile Discovery Center, trying to build a large, naturalistic Cuban swamp can be challenging but we try our best to mimic their home environment. Our exhibits have lots of plants and the water is a little murky. I try to let the trees overgrow as much as possible while still allowing visitors to view the animals.

Washington, D.C.’s summers are hot and humid, just like in Cuba. Cuban Crocodiles can bask in up to 115 degrees Fahrenheit. However, they also need somewhere cool to escape if they start to feel too hot. You can tell a Cuban crocodile is hot if they are sitting with their mouths open. Water is a good way for them to cool down. Our pools are very large, so the water takes a long time to get warm. We usually try to keep it below 80 degrees Fahrenheit during the summer.

The exhibits also have large skylights that are open all summer and we heavily water the plants to keep the exhibit at a good temperature. As we head into autumn and the temperature drops, we turn the heaters on, including heating fans in the ceiling, to keep the exhibit at an ideal temperature for the crocodiles.

Another element to housing Cuban crocodiles is grouping them. Cuban crocodiles typically live singly or in pairs at zoos. While they live well on their own and can live in larger groups, most zoos do not have enough space to house more than two Cuban crocodiles comfortably.

Here, we have two female-male pairings on exhibit: Blanche and Jefé, and Rose and Miguel. Behind the scenes, we have a female, Dorothy, and an 8-year-old male, Jésus. Jésus is too small to live with any of the adults, so he and Dorothy do not live together. Each Cuban crocodile has their own personality, but they are all very smart and in tune with their keepers.

We develop personal relationships with each of our Cuban crocodiles. Sometimes, our Cuban crocodiles will try to test their keepers. They know who brings them food and they’re very food motivated. So, when a keeper asks them to shift (move from one enclosure to another), they may not listen. Instead, they wait to see if the keeper will feed them anyway. You have to have a lot of patience to train a Cuban crocodile and learn to ignore those testing behaviors.

Dorothy and I have a really good relationship. In fact, it’s so good that I’m the only one she’ll cooperate with. Dorothy can be very stubborn and is notorious for ignoring other keepers when asked to shift out of her enclosure. She’s the old lady of our group and is our oldest Cuban crocodile, pushing 60 years old.

I also really enjoy working with Blanche, since she’s the smartest and most dangerous of our Cuban crocodiles. All our Cuban crocodiles are food motivated, but Blanche will charge when she shifts and when we are feeding her; she tends to do these things more aggressively than the others. That motivation, combined with her mental sharpness, makes it easy to train her.

As part of the positive reinforcement training program, our Cuban crocodiles are trained to move into their shift enclosure by name. If done correctly, the behavior is marked by a whistle and rewarded with some food. It is important to be able to shift the Cuban crocodiles this way because we cannot go into the enclosure with them. I can go in with our American alligator, for example, with a rake or other type of barrier and there isn’t going to be any close encounters. The Cuban crocodiles would just pull that rake right out of my hands and come after me. Shifting them off exhibit allows us to clean or maintain the habitat safely.

We also give our Cuban crocodiles enrichment! They receive ice treats for special event days at the Zoo, like International Family Equality Day and Valentine’s Day. The crocodiles smash the ice to get to the frozen mice inside. We also provide environmental enrichment by creating a light rain with the misting nozzle on the hose. Occasionally, we do carcass feedings and the Cuban crocodiles get a cow’s leg to rip up and enjoy. These feedings help strengthen their jaw muscles and the meat is rich in nutrients. The skin and bones are also full of fiber and aid in the digestive process.

Crocodiles are carnivores and our Cuban crocodiles are not picky. We feed them a rotation of different small mammals, birds and fish, along with croc biscuits. Croc biscuits are the crocodile version of dog kibble. They are a bit bigger than a golf ball and contain all the nutrients the crocodiles need.

Jéfe is our largest Cuban crocodile, weighing between 250 and 300 pounds. He’s older than our other adults, but not as old as Dorothy. He’s kind of a goofball at times and I’ve learned quite a bit from him. He tends to get himself in trouble and then act like he had nothing to do with it.

A few years ago, we were researching if Cuban crocodiles can see color with three 25-pound cinderblocks in one of the exhibits. Jéfe was in the exhibit with the cinderblocks and I was in the back watering plants. It was not feeding time, but Jefe wanted food. In frustration and maybe playfulness, Jéfe picked up one of the cinderblocks, took it in the water and threw it in the pool.

We did not know they were capable of picking these blocks up, let alone tossing them around. He picked it up and carried it like a human would a baseball. That is one of my favorite stories and we learned something new about Cuban crocodiles that day!

In addition to pursuing higher education, anyone hoping to work with Cuban crocodiles should get their foot in the door working with animals. Most zoos and aquariums offer internships for those 16 years and older, and some even have junior keeper programs for younger kids. There are always going to be things you can’t learn in books. Getting hands-on experience is the best way to obtain that knowledge.

Planning a visit to the Zoo? Stop by the Reptile Discovery Center to see the Cuban Crocodiles inside and be sure to walk around the outside habitats to see other crocodilian species. Plan your visit!

Jump into more stories from our keepers! Check out a variety of stories from all over Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute here.

Related Species: