How Do You Stomp Out An Elephant Disease?

How do you train an Asian elephant to voluntarily participate in trunk washes, blood draws and other medical exams? By building their trust and rewarding their participation with treats! These check-ups are vital for keeping the Zoo’s herd healthy and monitoring them for disease. Get a behind-the-scenes look at what goes into caring for elephants from Robbie Clark, assistant curator of Elephant Trails.

From left to right: Asian elephants Nhi Linh, Spike and Trong Nhi explore one of their outdoor habitats at Elephant Trails! Spike has a recommendation to breed with both females from the Association of Zoos and Aquariums.

What is one of the biggest health concerns for Asian elephants?

The elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus (EEHV) is a naturally occurring virus that both African and Asian elephants carry. There is not enough research to confirm how EEHV itself is transmitted, but most viruses are normally spread from one individual to another.

Our team here at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute first described the virus in detail—and how deadly it can be—in 1995, through the unfortunate death of our young Asian elephant calf, Kumari. Once EEHV enters an elephant’s bloodstream, it can replicate rapidly, become symptomatic and may lead to EEHV hemorrhagic disease—as it did for Kumari.

For three decades, we have been committed to learning everything we can about this virus, including why some elephants succumb to it while others survive. We established the National Elephant Herpesvirus Laboratory here at the Zoo’s veterinary hospital. The EEHV lab serves as a resource of information, testing and research for the elephant community worldwide. And, our staff have helped establish labs at zoos and institutions around the world.

Asian elephants Shanthi and her daughter Kumari enter a pool in their outdoor habitat on April 1, 1994. Kumari was 16 months old when she died unexpectedly April 26, 1995, from EEHV hemorrhagic disease.

Does EEHV affect elephants of all ages?

Elephants of all ages can carry EEHV latently—that is, the virus is dormant until conditions are right for development. Young elephants up to 20 years of age seem to be the most susceptible to disease from the virus.

For those of us who work with these animals, caring for a young elephant is the most exciting thing in the world. It’s also the most terrifying. We prepare as though it's not if a young elephant becomes symptomatic with EEHV—it’s when. That takes an enormous amount of time, effort and resources. And commitment doesn’t guarantee a good outcome—there is always a risk of devastating results.

Still, breeding Asian elephants in human care is worthwhile for many reasons, not the least of which is that this species is critically endangered. We recognize the risks that are involved with caring for a breeding herd of Asian elephants, and we have a comprehensive surveillance, treatment and response plan.

To track wild Asian elephants' movements in Myanmar, Zoo scientists use GPS collars like the one pictured here. Using this information, scientists and partners develop strategies for mitigating human-elephant conflict.

Does EEHV only affect elephants that live in zoos?

No. A common misconception about EEHV is that it only affects elephants in human care. That’s not the case—it affects wild populations, too.

Zoos have elephant experts, veterinarians and pathologists on staff who can monitor an animal’s health and investigate death in a timely manner. In range countries, it is much more challenging to study how EEHV affects wild populations. Scientists may not come across a body until days or weeks after its death—far too late to determine whether EEHV was the culprit.

What causes EEHV to turn deadly?

Once inside a host, EEHV can go into a latent (dormant) phase. Most adult elephants are able to fight the virus when it comes out of latency, because they have antibodies to the virus. They may experience only mild symptoms or no sign of disease at all.

For calves, the story is different. Research indicates that if a calf is exposed to EEHV while it is nursing and has maternal antibodies, it has a better chance of producing its own antibodies and surviving without experiencing serious disease. Calves that become exposed to EEHV after they have weaned (and lost those maternal antibodies) appear to be the most susceptible to succumbing to the disease.

Although we’ve learned a lot over the years, we haven’t found what causes the virus to go from latent to active and symptomatic. Research indicates that stress may be a factor.

For elephants, the wild is not an easy place to survive. Stresses include encountering predators and humans, getting separated from herd members, the birth or death of family members, the movement of individuals in or out of a herd, stormy weather and the list goes on. Zoo elephants may experience some similar events, particularly with the changing of herd members and moving from place to place.

Training gives elephant keepers an opportunity to examine each individual up close. They look for any changes in the elephants' movements, behavior or mood.

How do you monitor the Zoo’s herd for EEHV?

We use three methods to regularly monitor the members of our elephant herd: behavior watches, trunk washes and blood draws.

For our adult elephants—Spike, Trong Nhi, Bozie, Maharani and Swarna—we observe their behaviors daily. Elephants will intermittently shed EEHV in their trunk secretions over the course of their life, so we do weekly “trunk washes” to help us detect viral shed (more on that later).

Although she is currently healthy, Nhi Linh—our 11-year-old elephant—is still at risk of becoming symptomatic with EEHV. There are four subtypes of EEHV in Asian elephants: EEHV-1A, EEHV-1B, EEHV-4 and EEHV-5. All are present and active within our herd. For the next 10 years, monitoring Nhi Linh’s health will be our team’s priority.

In addition to behavioral observations and trunk washes, we collect blood samples from Nhi Linh weekly. We send the samples to our EEHV lab for analysis. Within hours, we learn if the virus is being shed and how much. We use those results to inform and adjust our herd management plans.

What behaviors do you look for?

Because keepers work one-on-one with our elephants every day, they know the normal “baseline” for each individual's behavior and health. We know their sleeping, eating, playing, exploring and socializing patterns.

When we see a marked change in these behaviors, we track them closely to determine if it is a one-off or if there’s another reason for this change in demeanor. For example, are they not getting along with another individual or group? Or is there an underlying health issue we need to address? In addition to changes in mood or behavior, we look for physical signs of illness: edema (swelling), lameness, loss of appetite or a change in their desire to interact with us.

One late indicator of an EEHV outbreak is a change in the color of an elephant’s tongue or mouth. This could also be accompanied by swelling around the mouth. We check Nhi Linh’s mouth every day and document it with photos so we can compare over time. Is her mouth a different color because she is showing symptoms, or did she eat sweet potatoes that turned her mouth orange?

Watch an Asian elephant participate in trunk wash training with our elephant care team!

What is a trunk wash?

During a trunk wash, we ask an elephant to present their trunk to our hand. Using a syringe, we inject saline into a nostril, then ask the elephant to raise their trunk for 30 seconds. On our cue, they then blow the solution into a sterile bag, and we place it in a test tube and send it to our lab, where it is analyzed for any viral shedding.

What does a blood draw entail?

During a blood draw, we ask an elephant to stand still and present their ear to us. This gives us full access to the blood vessels in the back of their ear. We then swab the site with an alcohol wipe and use a 21-gauge butterfly needle—the same one you would see at your doctor’s office—to obtain the blood. It takes anywhere from 30 seconds to several minutes to collect the sample size we need.

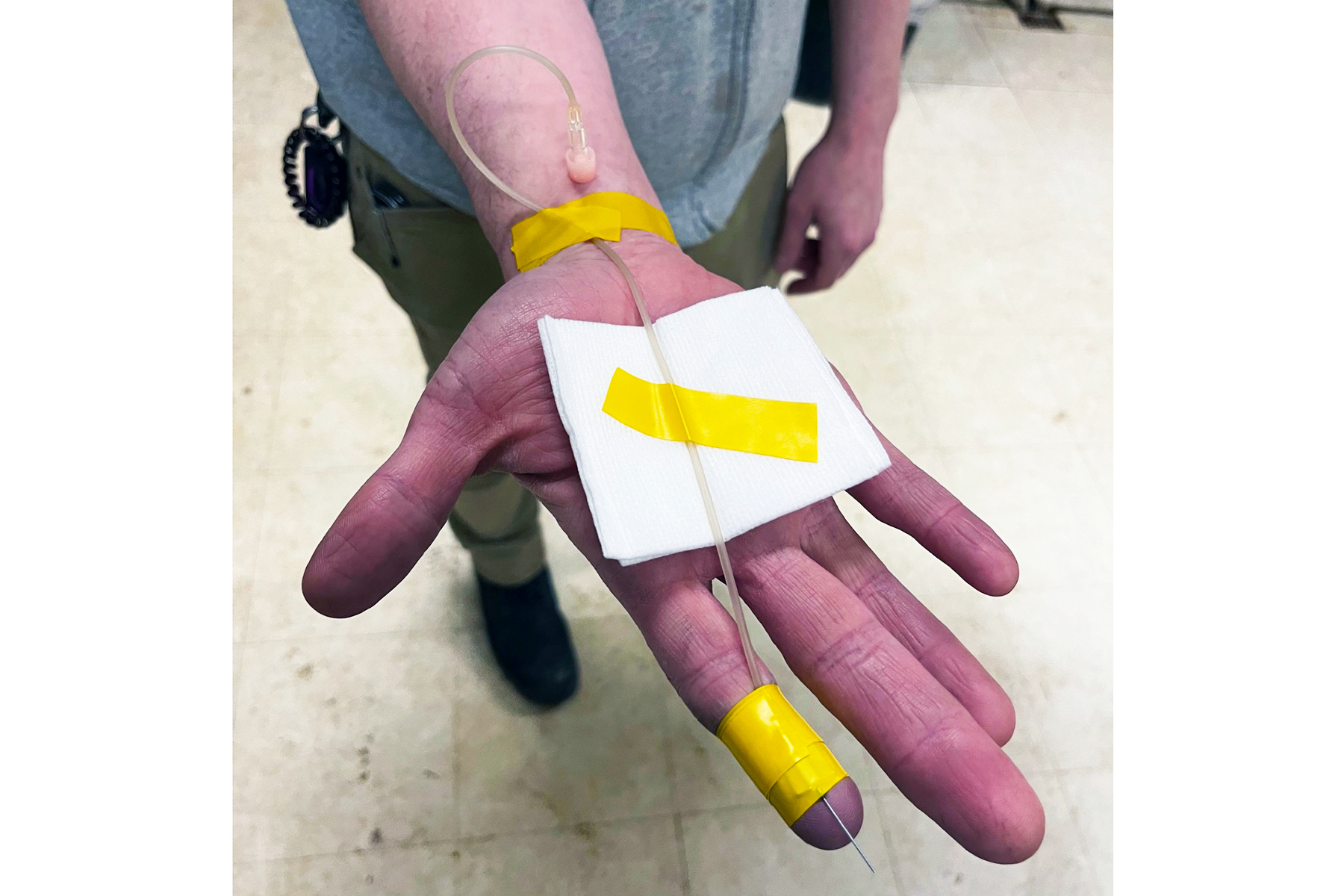

To desensitize Nhi Linh to the equipment used during blood draws, assistant curator Robbie Clark taped a blunt needle, tubing and gauze to his hand for two weeks.

How do you train Nhi Linh for blood draws?

Prior to coming to our Zoo, Nhi Linh had never voluntarily participated in blood draw training. We started from square one and taught her how to line up against the barrier, lean towards us, stick her ear through the bollards and hold still.

What challenges did you have to overcome?

Just like us, every elephant has a different comfort level with blood draws. Asian elephants have small ears, and it is challenging to collect blood from Nhi Linh’s veins especially.

For her, the biggest hurdle isn’t the needle stick itself, but the anticipation of what’s to come. To desensitize her to the blood collection supplies, I taped a blunt needle and tubing to my hand for two weeks. This helped show her it was just a normal part of her daily routine. There was nothing to be scared of.

During training, it became clear Nhi Linh did not like the steps prior to the needle stick. Normally, we follow a two-step process. Step one, grab the alcohol swab. Step two, grab the syringe. She did ok with step one, but she would flap her ear before step two.

We had to teach her that she should keep her ear outside the bollards and hold it still, regardless of what she’s anticipating. When we adjusted our training and picked up the swab and syringe at the same time, it seemed to help her worry less about what was happening behind her ear.

What are her rewards for participating?

At times, Nhi Linh gets nervous—she’ll wince and grab my hand with her trunk—but I reassure her. I talk to her and tell her she’s doing a good job, pet her and give her big handfuls of grapes. At the end, Nhi Linh gets a big “jackpot’ reward, half a watermelon, which is her version of ice cream.

Regardless of whether we are successful in drawing blood or not, we always reward her with food and lots of praise simply because she chose to participate. We want to make the experience as positive as possible. Ultimately, our goal is to be able to collect blood at any time, even during a medical emergency.

Asian elephant Spike participates in a blood draw.

Why are you training Spike and Swarna for large-volume blood collections?

EEHV can quickly become symptomatic. There is a very short window of time to successfully begin treatment. That’s why it’s important that we monitor our elephants’ health so closely. If we see subtle changes or detect viral sheds, we can start treatment right away.

One of the most effective treatments is a blood transfusion from other elephants. We want to have a blood supply ready to go if Nhi Linh becomes ill. Luckily, two of our elephants, Spike and Swarna, are matches for Nhi Linh’s blood type. Both voluntarily participate in large-volume blood collection as donors.

Our immediate goal is to bank enough blood for Nhi Linh’s needs. Down the road, we aim to have enough for future calves, as well as a supply we could donate to other zoos in need.

How do you train this behavior?

We always have at least three people present: one keeper who offers the elephant positive reinforcement (food and verbal praise), another who collects the blood and a veterinarian or credentialed veterinary technician who weighs the sample and processes it for banking.

There are two big challenges in training elephants for large-volume blood collection: the size of the needle and the amount of time we need them to stand still.

With this procedure, we use a 16-gauge needle, which is larger than the 21-gauge used for regular blood draws. The process of desensitizing them to that takes time. Spike was a champ right off the bat. Swarna wasn’t so sure at first but ultimately did a great job.

Spike has very large ear veins, so we let gravity do the work during his large-volume collections. Blood flows from the vessel through the tubing into the collection bag. It can take up to 10 minutes to collect 500 milliliters of blood from Spike, depending on the flow. To put it in perspective, that’s a little more than the pint a human would typically donate.

Swarna’s ear veins don’t flow as well as Spike’s. For her, we pull the blood sample into 20CC (20 milliliter) syringes using a special extension set. Then, using a 3-way stopcock, we change the direction of the flow of blood and push the sample into the collection bag. It’s a lengthy process that can take up to 25 minutes to fill the bag. Swarna’s patience for standing still and participating in this collection is impressive!

What are their rewards for participating?

Throughout the procedure, we reward Spike and Swarna’s participation with food and verbal praise. They aren’t picky eaters, so we mostly offer them grain, which is part of their normal diet. When the needle stick comes, they receive a higher-value reward, such as a banana, sugar cane or melon. At the end, they get a “jackpot”—another high-value reward. This lets them know they did a good job, and we want them to do it again next time!

Nhi Linh (foreground) and Spike hang out by the pool in their outdoor habitat.

What makes you optimistic about our elephants' future?

Zoos that are members of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums—including us— have learned so much about EEHV and its effects on elephants over the last few decades. But we still have more to learn about the virus and its different subtypes.

Collectively, we are working to figure out what makes some elephants more resilient to EEHV than others. And we hope to answer some lingering questions. What causes EEHV to onset and make an elephant ill? What treatments will help an elephant effectively fight the virus? When exactly do young elephants graduate beyond the level of concern? Several zoos are also working on an EEHV vaccine.

EEHV is a high priority for our elephant program here at the Zoo, and we are committed to being a leader in EEHV research. As we breed Asian elephants—and hope to welcome calves in the future—we are not daunted by the risk that they will be susceptible to this deadly disease. By closely monitoring our elephants’ health and banking blood for treatment, we will be prepared if or when the virus becomes symptomatic in one of our elephants. We are determined to stomp out EEHV, safeguard our elephants and see them prosper under our care.

Get to know the Zoo’s elephants in this update from the Elephant Trails team. Curious to know more? See how they trimmed Spike’s tusks, helped Swarna when she had a toothache, and obtain our elephants’ weights! Visiting the Zoo? Catch elephant keeper talks every day at 3 p.m.

What can you do to help Asian elephants? When you volunteer, become a Zoo Member or make a donation, your support helps us conserve and protect endangered species, including Asian elephants. Learn how you can join our conservation community.

Related Species: