Saving Cheetah Cubs One Drop of Milk at a Time

In case you haven’t heard, there was a breakthrough in cheetah conservation recently: the first cheetah cubs were born via embryo transfer at the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium in Ohio! Our Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute scientists were key in making this happen.

But our science doesn’t stop at the birth. There is a lot that goes into raising endangered animals. One of the key things is how to feed them — especially when they are babies and should be relying on their mother’s milk but for some reason can’t.

That’s where I come in. As a research assistant with the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute’s milk bank, I work on analyzing and replicating animal milk. It is incredibly important work, because mother animals can’t always care for their young, and every individual is important when we are dealing with endangered and vulnerable species. The Smithsonian has the world’s largest milk repository, with more than 17,000 samples from about 200 species. The Columbus Zoo’s cheetah, Izzy, who gave birth to the cubs via embryo transfer, is the latest donor to our milk bank.

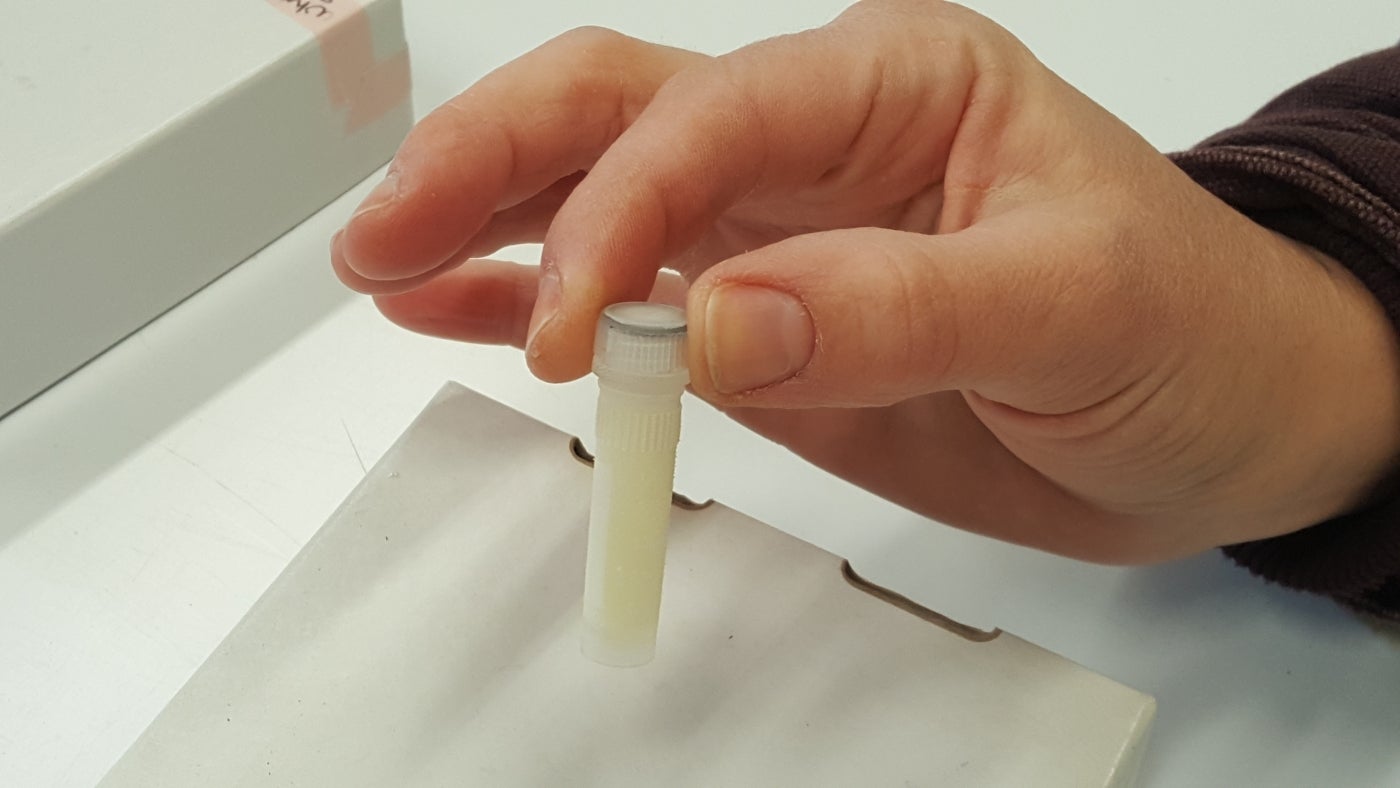

While Izzy’s cubs are being hand-reared by keepers at the Columbus Zoo, she is still able to contribute to their well-being by donating milk. Izzy was also raised by keepers, and they have spent years training her to voluntarily participate in medical procedures. This means keepers can milk her by hand, using a typical human hand-held pump, and send us a sample of her milk. It is a rare opportunity to study a cheetah mother’s milk, as most large cats won’t tolerate this kind of hands-on contact. We can usually only get milk samples when a big cat is asleep, and we try not to intervene or do checkups with a mother while she is caring for her cubs. Izzy is a wonderful exception, due to her relationship with her keepers.

To be able to help future cheetahs, we need the milk to travel more than 400 miles across the country without spoiling. Keepers ship the milk on dry ice packaged in a cooler. We eagerly track the package to make sure that, once it arrives, we can quickly put the samples into our freezer with the other milks we keep in the repository. This will be the first cheetah milk that the repository will receive.

Once we get the milk, we run nutrition analyses, which can help us better understand mammalian milks. At the Smithsonian nutrition laboratory, we can analyze milks to see how much fat, protein, sugar, calories, calcium, phosphorus and other minerals are present. We can even test to see what microbes may exist in a mother’s milk.

The data we collect from the Smithsonian milk repository has multiple applications to scientific research and clinical cases. For clinical cases, we may have to hand-rear animals for a multitude of reasons, including a mother rejecting her infant, a mother being unable to produce enough milk, an infant having trouble nursing, or a baby or mother getting sick. By understanding the composition of a mother’s milk, we can better create an appropriate milk substitute. Since no two milks are alike, it is always optimal to get as much information on a species’ milk as possible.

Zoos that are accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums have successfully hand-reared cheetah cubs, but we do not have a specific cheetah milk formula. Our formulations are based on big cat milk formulas and are consistent with nutrition composition analyses done on a few cheetah mothers. There is only a small sample size of cheetah milks, so it is always good to add to that and to test the milks with our modern-day technologies. Overall, we do know and expect the cheetah milk to be high protein. If you think about it, a cheetah’s diet is high protein from meat, so the cubs will also have a high protein milk.

The cheetah milk is of scientific interest to the Smithsonian milk repository team because it adds another piece to the great mammalian lactation puzzle. Dr. Michael Power has spent years formulating and connecting an evolutionary tree of milks. Even though the nutritional content of milk is related to the diet of the animal, the milk composition follows the species’ evolutionary trends as well. This provides another avenue to understand mammalian evolution. With the Columbus Zoo’s help, we are one step closer to deciphering the mystery of milk.

Related Species: