Test Flight: Which Harness Will Help Siheks Soar?

The countdown to the Guam kingfisher’s reintroduction to the wild has begun. Before these birds, also called siheks, can soar over the Palmyra Atoll, scientists need to determine which harness materials can carry a tracking device and stand the test of time. That’s where six of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s kingfishers come in. Bird keeper Erica Royer shares how scientists and siheks are working together towards the goal of releasing one of the world's rarest animals back into the wild.

What are your favorite facts about Guam kingfishers?

Guam kingfishers—called sihek (SEE-hick) in the Chamorro language (the language of the indigenous people of the Mariana Islands)—can be very vocal, especially during the breeding season. Before their populations were decimated by the invasive brown tree snake, it was said you could tell the time just by listening for the birds’ calls because they often vocalized around the same time every day.

During the breeding season, a pair will take turns excavating a nest cavity together. When they find the perfect place to nest, they fly from a branch and strike the spot once with their bill. It can take some time to build their nest cavity, since they do not hammer away at a tree like our native woodpeckers would.

What are their personalities like?

Young siheks tend to be curious and ornery. They pick at and peck every branch, leaf and object as they explore their surroundings. At every age, these birds are very secretive. Often, our bird team only gets to see these exploratory behaviors—as well as bathing, feeding and breeding—on our closed-circuit cameras.

How is the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute helping siheks?

Siheks are the rarest animals in the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute’s collection. When we first took these birds under our wing in the 1980s, there were only 29 individuals left in the world. For decades we have worked with other Sihek Recovery Team partners to crack the code of how to care for and breed this amazing species.

Thanks to these efforts, their numbers are growing. SCBI hatched its first chick in 1985. Since then, 22 chicks have hatched here as part of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ Guam Kingfisher Species Survival Plan. Today, there are 140 individuals in human care, and SCBI cares for 12 of them!

Siheks are considered extinct in the wild by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. As breeding programs in conservation facilities like ours gain momentum, there is an incredibly exciting opportunity for us to reintroduce this species to its native habitat in Guam (once brown tree snake numbers reach a more manageable level, of course). The birds will initially be released on Palmyra Atoll until it is safe to release birds in Guam.

Is SCBI playing a role in reintroduction efforts?

Yes! When conservationists consider whether it is possible to reintroduce a species to its native habitat, one of the critical components we study is how animals move and utilize the landscape. For birds, that often involves outfitting them with small transmitter “backpacks” (i.e. tracking devices) that help scientists locate the animals and study how they are adapting to the landscape after release.

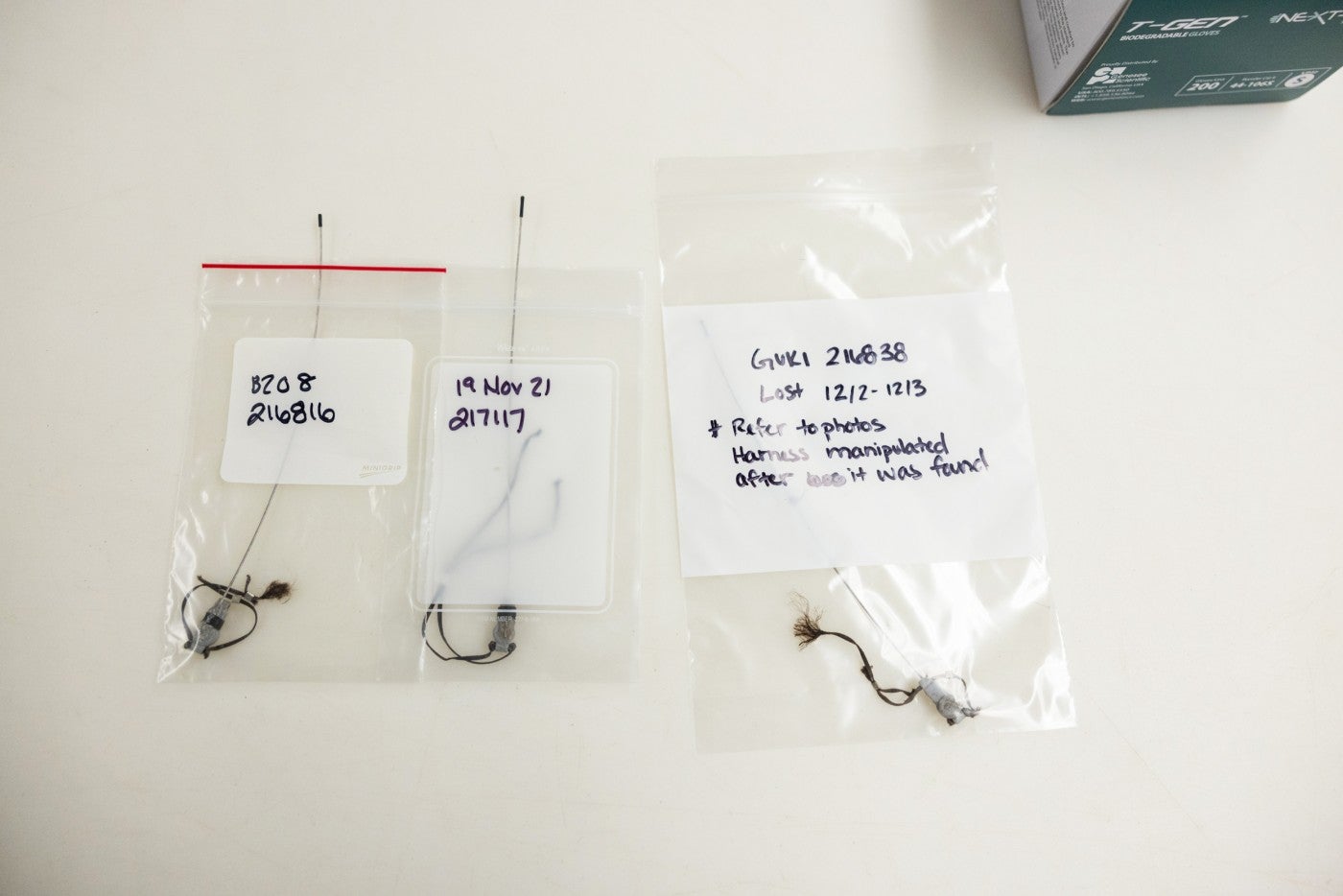

With preparations to release birds to the wild underway, we here at SCBI are using transmitter replicas—created from a 3-D printer—and testing different types of harnesses. There are many different ways to attach tracking devices to birds, depending on the species. This has not been done with siheks before, so we have to consider what attachment method would be best.

How are you testing the harnesses’ fit?

The replica devices and harnesses weigh between 1.8 grams and 2 grams—less than a dime! Our birds weigh between 55 grams and 65 grams, so together the device and harness weigh less than 3 to 5% of the birds’ body weight. To put it another way, that is like a 160-pound person carrying a backpack that weighs 5-to-8 pounds.

Only single male siheks are participating in this study. At SCBI, those birds include some that you have read about in our recent blogs, including Fuesta, Animu, Gekpu, Chubasca, Antonio and Aprile! For each phase of the study, four birds are fitted with transmitters and the remaining two are in our control group.

To test which harnesses work best, we are looking at several different elements. Do the harnesses stay on the birds for 90 days—the life of the battery that will be used in the real transmitter? Siheks have very strong bills—are they able to remove the transmitter before it is meant to fall off? Lastly, does the presence of the transmitter change the birds’ behavior? We monitored their behavior before they were fitted and afterwards to see if there were any changes in their daily preening, foraging and resting activities.

The trial is ongoing, but the goal is for our birds to wear the harnesses for 3 months. Gekpu is the only bird currently still wearing a harness in Phase 2 of the study.

What have you learned from the trial thus far?

We should be able to safely monitor the birds post release to ensure their well-being and survival! The birds have strong bills, so we have made some adaptations to the harness to account for that.

Being able to track released birds will allow us to monitor their behavior, including what they eat, how they spend their time, how far they disperse and if they interact with other released siheks. Testing out these harnesses is a very important step in the translocation process for this species, so it is very exciting to be part of this project.

I look forward to the day where we can see our efforts come full circle and release birds into the wild!

This story appears in the February 2022 issue of National zoo News. Get to know our Guam kingfishers at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in these updates from animal keeper Erica Royer!

Related Species: