Physical Description

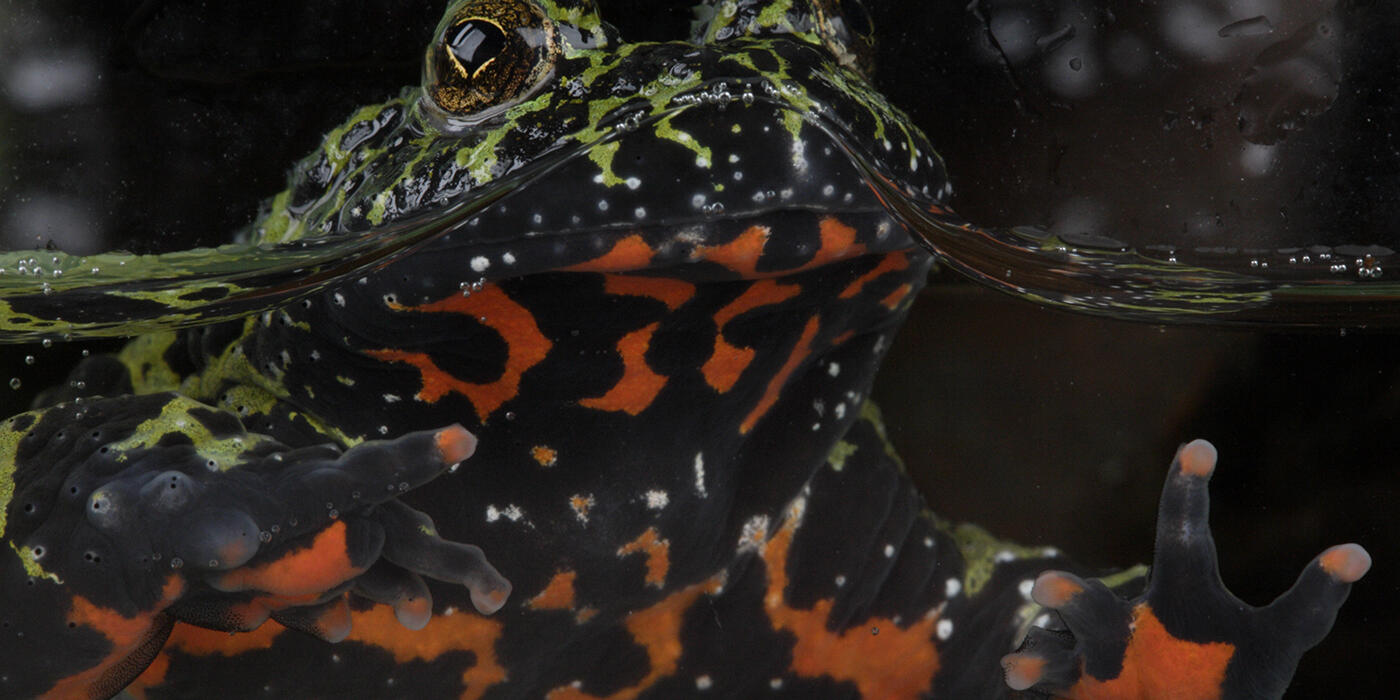

The back is covered with rough warts, or tubercles, and is brown-gray to gray-green or bright green with dark spots or striations. The belly is smooth and marbled red or red-orange to yellow with dark spots. The red coloring warns would-be predators that this toad's skin is poisonous. The milky substance secreted by their skin irritates the mouth and eyes of attackers. Unlike most toads, the pupil of their eye is triangular. Males, unlike females, also have nuptial pads on the first and second fingers.

Size

They reach a maximum length of 2 inches (6 centimeters).

Native Habitat

Fire-bellied toads live in northeastern China, throughout North and South Korea and in the Khabarovsk and Primorye regions of Russia. A small, introduced population lives close to Beijing. Records of this species from southern Japan (Tsushima and Kiushiu islands) are now believed to be in error. An aquatic species, these toads spend the majority of their time in slow-moving streams and ponds. Habitats also include mixed, coniferous and broad-leaved forests, open meadows, river valleys and swampy bush lands. Breeding typically occurs in streams, pools, paddy fields, ditches and other stagnant bodies of water. The toads hibernate in the winter, generally choosing rotting logs or leaf piles for their burrows from September to May. This species can adapt to modified habitats. At the end of summer, the species can be found on land at distances up to 1,000 feet (300 meters) from water.

Lifespan

These toads are one of the longer living toads, frequently living to be 12 to 15 years old. In human care, they can reach 20 years of age.

Communication

Unlike most frogs and toads, they do not have a tympanic membrane, or eardrum. Unlike most frogs and toads, male fire-bellied toads do not have a resonator; they actually make calls through inhalation rather than exhalation.

When threatened, the oriental fire-bellied toad uses a distinctive defensive posture. It bends its back downward, forming a concave surface, which reveals the edges of its bright belly. It also hold its limbs up and arches its head in a posture called the "Unken Reflex."

When actually provoked or attacked, a second defensive phase comes into play where the toad flips onto its back to reveal the full extent of its warning colors. Should provocation continue, the toad secretes a milky toxin from the hundreds of tiny pores located throughout its body and is thus coated. Once a predator tastes this toxin, it will rarely if ever attack again, although grass snakes and other water serpents are known to attack and devour these toads without ill effects.

Food/Eating Habits

This family of toads cannot extend their tongues like other toads or frogs. To feed, they must leap forward and catch their prey with their mouths.

Larvae consume detritus, various algae, fungi, higher plants and protozoans. The tadpole diet widens as it matures because of an increase in plant and animal diversity. They begin eating terrestrial invertebrates before they complete metamorphosis while the toadlets still have a small tail. Adult food consists of terrestrial invertebrates including worms, mollusks and insects.

At the Smithsonian's National Zoo, they eat small crickets three times a week.

Social Structure

Fire-bellied toads tend to be gregarious.

Reproduction and Development

The toad hibernates from fall to late spring in in groups of one to six individuals. They hide in rotten trees, heaps of stones and leaves, or underwater in streams. When warmer temperatures arrive in mid-May, the toads emerge and start breeding.

Males float on top of the water with their legs splayed, calling with a sound like the gentle tapping of a musical triangle: a "ting-ting" sound that rarely lasts longer than 15 seconds.

Mating usually occurs at night with males grasping the females just in front of the hind limbs, a position known as amplexus. To aid their grip, males are equipped with rough nuptial pads on the inner thumbs, although uninterested females are inevitably able to squirm their way out. Males will often work themselves into such a frenzy that they accidentally grasp on to anything that looks remotely like another toad, including floating twigs, plants, other frogs and toads, newts, fish and even human fingers.

The reproductive period is very long within each population because different females deposit eggs at different times. Breeding pairs are formed randomly. If mating is successful, females will deposit 40 to 110 eggs either individually or in small clumps of about four to 25 eggs very close to the water surface where the warmth of the sun (spotlight) can aid embryo development. After about six to eight weeks, hind limbs begin to appear, one from the spiracle, which marks the beginning of lung development. Tadpoles can frequently be seen surfacing to take gulps of air. After eight to 14 weeks, the tadpoles enter a critical phase when they begin to metamorphose into fully air-breathing amphibians. Tadpoles complete metamorphosis usually by the end of August or September.

Conservation Efforts

This species as one of least concern because it has such a wide distribution, presumably large population, and because it is unlikely to be declining fast enough to qualify for listing in a more threatened category.

Oriental fire-bellied toads are threatened by habitat loss and degradation. In Russia, the collection of animals for traditional Chinese medicine may be a potential threat. Moderate numbers are exported mainly to Western Europe and North America in the international pet trade.

This species is present within a number of protected areas in China and Korea and six nature reserves in Russia. It is listed on the Red Data Book of Khabarovskii Region, Russia. There is a need to monitor the relatively small Russian population.

Help this Species

Reduce, reuse and recycle — in that order! Cut back on single-use goods, and find creative ways to reuse products at the end of their life cycle. Choose recycling over trash when possible.

Choose your pets wisely, and do your research before bringing an animal home. Exotic animals don’t always make great pets. Many require special care and live for a long time. Tropical reptiles and small mammals are often traded internationally and may be victims of the illegal pet trade. Never release animals that have been kept as pets into the wild.

Share the story of this animal with others. Simply raising awareness about this species can contribute to its overall protection.

Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. (n.d.). Oriental fire-bellied toad. Retrieved February 24, 2026, from https://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/oriental-fire-bellied-toad

Animal News

Elephant Calf Update: Building Bonds Among the National Zoo's Herd ›

Get To Know the National Zoo's Growing Sloth Bear Cubs ›