Hoppy Amphibian Awareness Week!

'Hoppy' Amphibian Awareness Week! All week long, the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute will be sharing stories about amazing amphibians and the scientists working to save them from extinction. Follow along below and on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter with the hashtag #AmphibianWeek.

May 1 | Amphibians Through Time

Japanese giant salamanders breathe through their skin, have impossibly small eyes and can grow up to 5 feet long! Get the scoop on these freshwater giants from Reptile Discovery Center keeper Kyle Miller. Read the Q+A here.

May 2 | Amphibian Superpowers

Did you know that salamanders can *literally* give you a hand—then grow it back? Check out Reptile Discovery Center keeper Matt Neff’s top 6 salamander facts! Read the keeper update.

The secret to salamanders’ survival may be in their slimy secretions. Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute scientist Carly Muletz Wolz is swabbing salamanders in Shenandoah, looking for disease-fighting microbes that live in the mucus on their skin. Get the scoop in our scientist Q+A.

May 3 | Meet an Amphibian

Celebrate Amphibian Week with an interactive online tour from the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. What is an amphibian? Why are they important? Explore these questions and more as you learn about the three groups of amphibians and what you can do to help conserve them. Take the virtual tour!

Meet the cutest clump of “moss” you ever did see: the Vietnamese mossy frog! In spring, the Reptile Discovery Center team celebrated the arrival of 50 hatchlings. Learn what it takes to set the mood for mossy frog mating from assistant curator Matt Evans. Leap to the Q + A.

May 4 | Meet an Amphibian Biologist

Learn why frogs matter and how you can help frogs from our colleagues at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Amphibians—animals that live in water and on land—need specialized habitats, atmospheres and food in order to thrive. Leap into learning what it takes to care for some of the frogs found in Zoo Guardians and at Smithsonian’s National Zoo from Matt Evans, assistant curator of the Reptile Discovery Center. Read the update.

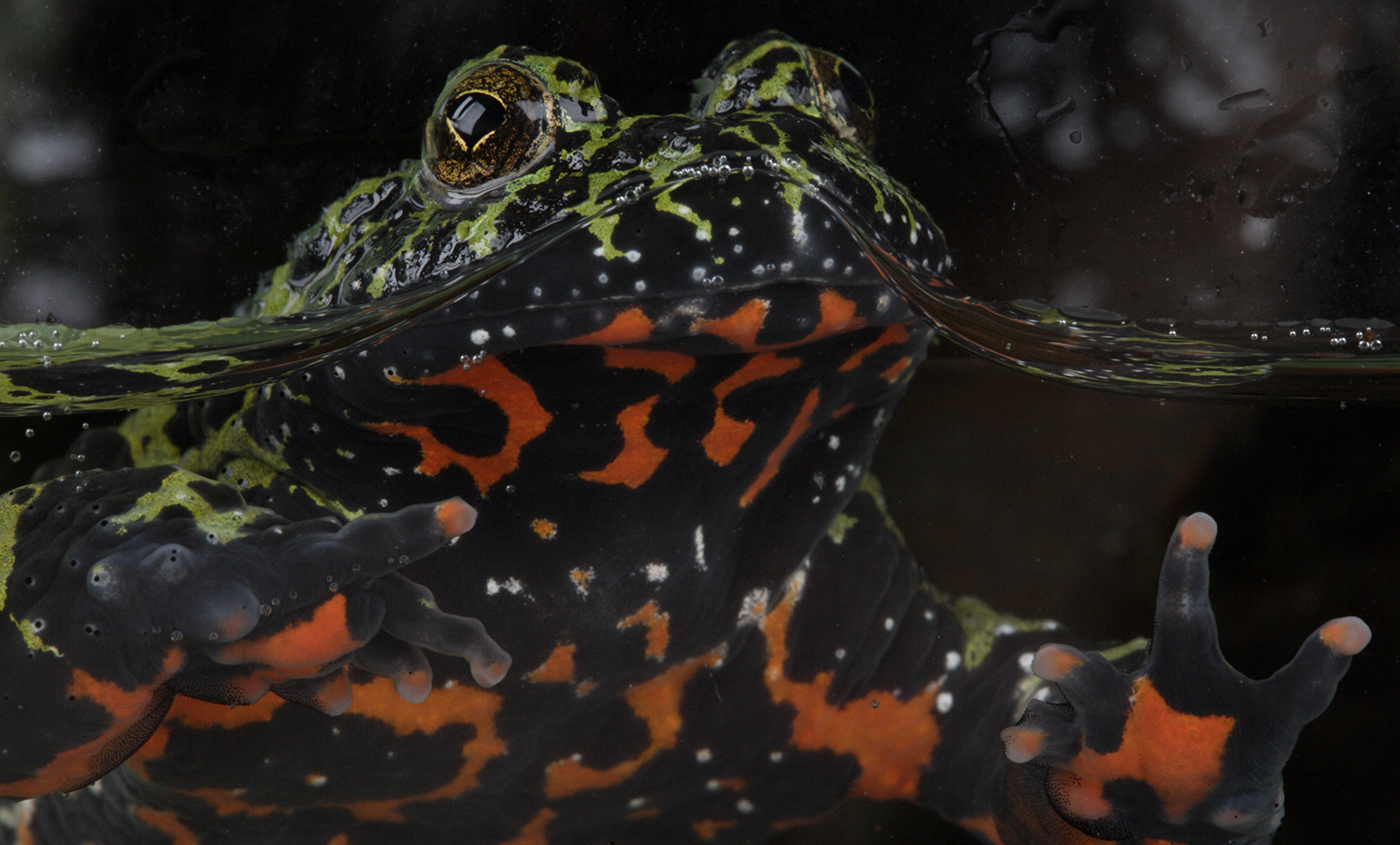

Take a close look at these frogs. Even though they differ in color, pattern and shape, they are all the exact same species! Using DNA barcoding, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute scientist Jessica Deichmann and partners at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History are working to identify these “masters of disguise.” Read the Q+A here.

May 5 | Name That Amphibian

With a sleek, eel-like body and beady eyes, the aquatic caecilian is quite an unusual amphibian! Check out some of Amazonia keeper Denny Charlton’s favorite fun facts about these wiggly wonders. Check out the keeper Q+A!

Can you tell a fantastic frog from a terrific toad? (Hint: there are 4 key differences between them.) Test your amphibian knowledge with the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project! Hop over to Amphibian Rescue to learn more!

May 6 | Amphibians on the Move

How do frogs survive, thrive and breed in the wild? Armed with tiny radio transmitter “backpacks,” these Limosa harlequin frogs are helping Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute scientists better understand amphibian lives in Panama’s rainforest. Partners at the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project help us keep track of the frogs’ movements. Learn more about their research.

The Appalachian ecosystem is home to more salamander species than any other region on the planet. Of the estimated 700 salamander species in the world, 54 call Virginia home. Take a (virtual) trip and salamander sleuth alongside our Reptile Discovery Center team!

May 7 | Amphibians are Important

Swift waters rush us into Salamander Saturday, celebrated on the first Saturday of May! Check out how Reptile Discovery Center animal keeper, Matt Neff, cares for and studies the largest salamander in the Americas: the hellbender. Read the update.

For decades, scientists have wondered whether the key to saving frogs from the deadly chytrid fungus lies in their skin. Could they genetically modify bacteria found in the frogs’ mucus layer and boost its antifungal properties, in effect creating a “living pharmacy” on the frogs? Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute scientist Brian Gratwicke and partners set out to test whether probiotics could protect the frogs from their fungal foe. Find out in this Q+A with Dr. Gratwicke!