Case Study: Restoring Life-supporting Andean Wetlands

Challenge

In the tropical high Andean Mountains, bofedal wetlands receive, retain, filter and regulate underground waters. A private company wanted to develop a gas pipeline in Peru that would cross hundreds of kilometers of coastal and Andean habitats, including bofedales, with minimal impact to these critical wetlands.

This case study explores how scientists from the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s Center for Conservation and Sustainability designed a Biodiversity Monitoring and Assessment Program for the project. In the process, CCS scientists discovered how little was known about bofedales. It became a priority for them to study and understand these wetlands.

Background

Bofedales are wetlands unique to the Andes that occur at elevations of more than 13,123 feet (4,000 meters). They are adapted to harsh climates -- intense solar radiation, extreme daily temperature changes, strong winds, and in some regions, a long dry season. They form near creeks, springs, lakes and underground water sources, but they can also be human-made. Most patches have flat, cushion-like plants intermixed with water ponds. During the dry season in the Andes, bofedales become the main source of water, food, refuge and nesting sites for wildlife and livestock.

Bofedales can be considered a peatland. Peat, or turba, develops underground as water saturation causes the slow decomposition of organic matter. Bofedal peats help regulate the flow of groundwater and store carbon. They can be a few centimeters to 26 feet (8 meters) thick.

Bofedales are disappearing due to human activities, such as the extraction of peat for fuel and organic gardening soil, overgrazing by livestock, and the construction of roads. Activities like mining can destroy entire wetlands and contaminate groundwater. Climate change worsens the issues, and the disappearance of glaciers jeopardizes the influx of water to these life-supporting ecosystems. The Peruvian legislature recognizes bofedales and other wetlands as fragile ecosystems that need to be conserved.

Gas Pipeline Construction

The company determined their gas pipeline would have the least impact by traveling along mountain ridges and hills, going around fragile habitats and across steep terrains. The pipeline crossed a few bofedales, so they took steps to minimize the impact, including:

-

Removing mats of plants and soil, and placing them carefully aside

-

Reducing the width of the ditch for the pipeline and installing a narrow road for machinery to travel

-

Burying the pipeline superficially to avoid disturbing underground water sources

-

Covering the pipe with the soil and plants they had initially moved

The total area under their management resembles a 25-meter-wide, 408-kilometer-long road along the pipeline, known as the right-of-way. As gas transport began, the company started to restore habitats impacted by the right-of-way.

Evaluation and Analysis

CCS scientists are helping the company measure its impact. For more than 11 years, scientists have led experiments to understand bofedales. They create the methodology for field assessments, collect and analyze data, use indexes and figures that are accessible to company managers when sharing results, and provide recommendations for restoring bofedales. Their Biodiversity Monitoring and Assessment Program has included:

- Updating the list of bofedals along the right-of-way. Bofedales can be difficult to distinguish from other types of Andean wetlands. CCS gathered experts in bofedal plants, birds and satellite imagery. Their work showed that some bofedales along the right-of-way were other types of wetlands, which helped the company concentrate their restoration efforts.

- Assessing plant life on bofedales adjacent to the right-of-way. CCS found that bofedales along a 124-mile (200-kilometer) strip are rich in plant species. They are separated geographically into three groups that correlate with the region’s precipitation gradients (the amount of rain each area gets). For example, the bofedales in the eastern region received more water and recovered faster than those on the western side.

- Monitoring plant life on bofedales crossed by the right-of-way. CCS continues to track the recovery status of each bofedal patch over long periods of time. They also created methods for more quickly assessing plant life in order to give timely updates to the company.

- Reviewing the effectiveness of fencing. CCS showed that placing fences around bofedales can help prevent livestock from grazing on plants, supporting their recovery.

- Understanding the hydrology of bofedales. Hydrology is a key factor in the life of these wetlands. CCS studied the depth of underground water in bofedales during dry and rainy seasons, and its effect on vegetation.

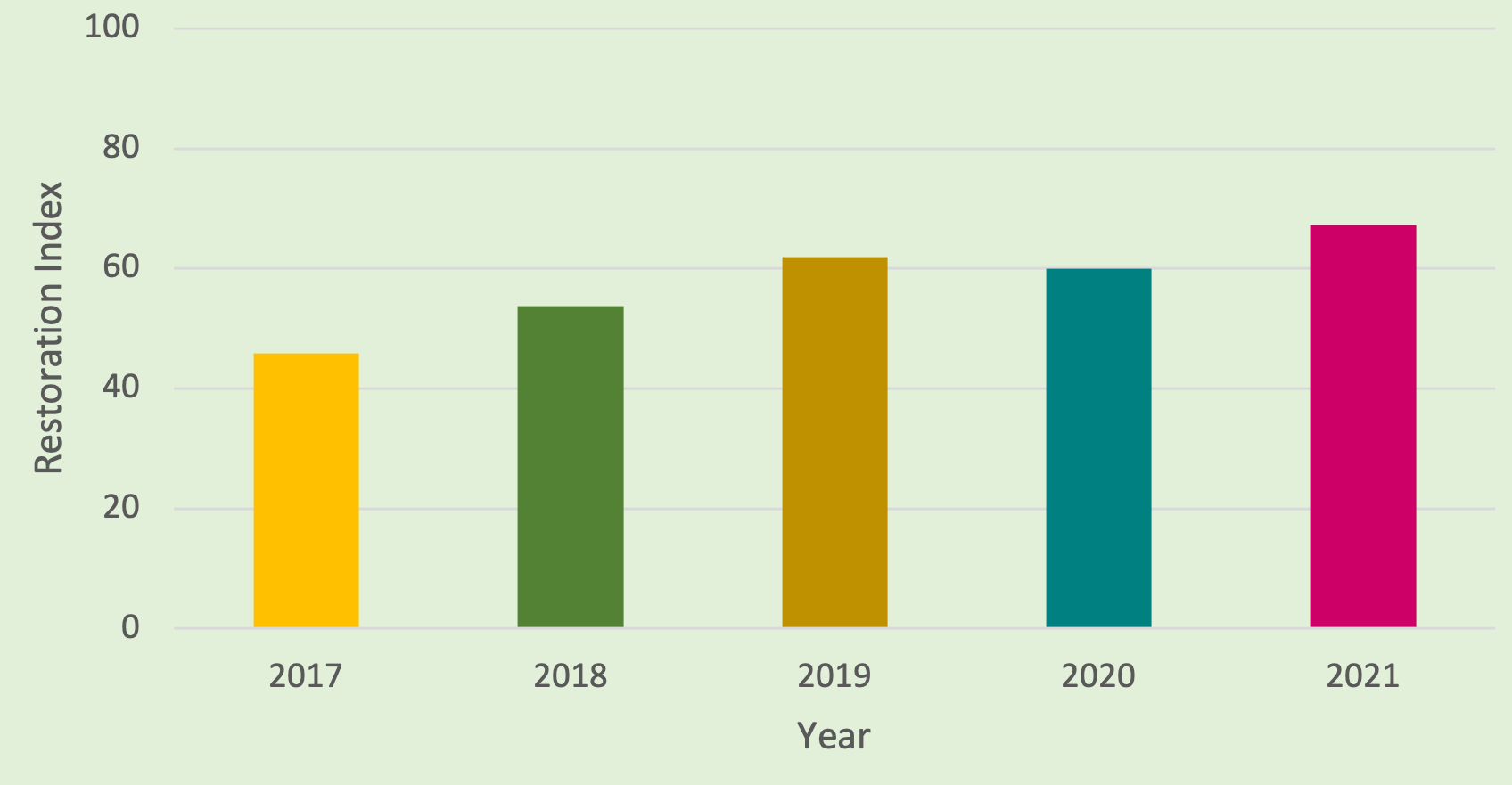

- Creating a restoration index. The index ranges from 1-100, with 100 representing that a bofedal has completely recovered. The index gives a general idea of the relative change in a bofedal’s restoration over time.

Milestone Solutions

CCS’s work shows that, with time and adaptive management, bofedales crossed by the right-of-way can recover their plant life and biodiversity. Their methods have so far provided:

- An inventory and analysis of the plant species found in bofedales

- An understanding of bofedal recovery patterns

- Rapid response strategies for bofedal restoration

- New insights into how bofedales function and how best to manage them

Using a tool for visualizing scientific data, CCS built maps and charts to share historical data about bofedales under study and management. This interactive tool gives managers the ability to review data, add new data as it is collected from the field, and make decisions informed by research.

The BMAP has resulted in a better scientific understanding of bofedales. Data shows that these wetlands support different plant communities, and each may require a different restoration approach. The BMAP also showed that focusing on one variable – in this case, plant species composition – can provide enough data to understand and manage a habitat.

Recommendations

Create a Biodiversity Assessment and Monitoring Program as early as possible. Benefits include:

- Designing a project with a smaller environmental impact

- Collecting baseline data on a habitat early in order to measure change

- Ability to monitor impact at all project stages

- Science-backed strategies to protect biodiversity and restore habitats

Plan to have monitoring programs for about 10 years. Long-term programs provide clearer data on natural ecosystems, especially those with slow biological processes. Because bofedales are located at high altitudes with low temperatures, plants may grow, disperse and colonize new areas more slowly. Shorter programs can miss impacts that only become apparent after longer periods of time.

Work with qualified scientists on the species, habitats and impacts of concern. Regular coordination and communication with experts results in reliable data that saves time and money.