Conserving the Last of Guam’s Avifauna: The Recovery of the Guam Rail

Walking through the forests of Guam the sound is arresting — because it’s silent. But the sound of the forest is returning. Nearly 40 years after being declared extinct in the wild, on some nearby islands you can hear the loud whistle of the Guam rail in forests again. After being one step away from extinct, the International Union for Conservation of Nature announced that the Guam rail had made a comeback at the end of 2019 and is now classified as critically endangered. It is only the second time in history that a bird species has recovered from being extinct in the wild (the first was the California condor).

The Guam rail, referred to locally as the ko'ko', was once a common bird with an estimated 60,000 to 80,000 birds in Guam during the late 1960s and early 1970s. However, the species was almost lost entirely due to predation by the invasive brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis). The snake is thought to have been accidentally introduced to Guam aboard military cargo ships following World War II.There are no large snakes native to Guam, so the birds, or avifauna, that lived there did not stand a chance against the arboreal predators. In a relatively short time period, the snake spread across the island and wiped out 10 of the 12 species of forest birds, several of which were endemic.

The brown tree snake is a perfect example of how an invasive species can disrupt an entire ecosystem. It has not only wreaked havoc on the birds in Guam but also resulted in the disappearance of six of 11 native lizards and two of three native bat species. The loss of these species has caused cascading effects on the island’s forest ecosystems.

Guam’s birds are like gardeners. As they move through the forest, they disperse the seeds of the fruit and plants they consume. When the birds began disappearing, so did the forest. There is now less diversity in the species of trees that grow, and the forests are thinning. In addition, spider populations have exploded because there are no birds to prey upon the insects. Apart from disrupting Guam’s ecosystem, the brown tree snake has also had significant economic consequences due to its affinity for climbing power lines, which causes frequent power outages on the island.

The effort to save the Guam rail began in the early 1980s when biologists from Guam’s Department of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources captured the last 17 birds to start a breeding and recovery program. One of the first transfers of birds from Guam to the mainland United States occurred in 1985, when 12 birds were brought to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute.

Guam rails are territorial birds and at first proved to be quite difficult to breed due to mate incompatibility and aggression. Once breeding success improved, Guam DAWR started releasing birds to create an experimental population on the island of Rota. Though the species was not previously found on Rota, releasing large numbers of birds on Guam was not yet an option. The snake was still found in high densities and was proving to be a difficult species to eradicate.

The first bird releases on Rota occurred from 1989 to 1990. Over the next couple of decades, Guam DAWR biologists learned which parts of the island the rails would thrive on, what the best release methods were, how to track and monitor the birds, and how to control feral cat populations so that the birds could succeed in a snake-free habitat. Now there are around 200 birds living on the island, and more importantly, they are producing their own offspring.

In 2010, 16 Guam rails were released on Cocos Island, which is a small, uninhabited daytime resort island 1 mile south of Guam. The island can only hold a small number of rails due to its size (1,600 meters long and about 300 meters wide), but the population of 60 to 80 Guam rails there is flourishing and is considered self-sustaining.

The Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute has successfully bred multiple Guam rails for the reintroduction program. SCBI once served as one of the quarantine facilities for birds hatched on the mainland that were destined for Guam. Today, all of the chicks produced at SCBI are slated for repatriation to Guam and eventual release to the wild.

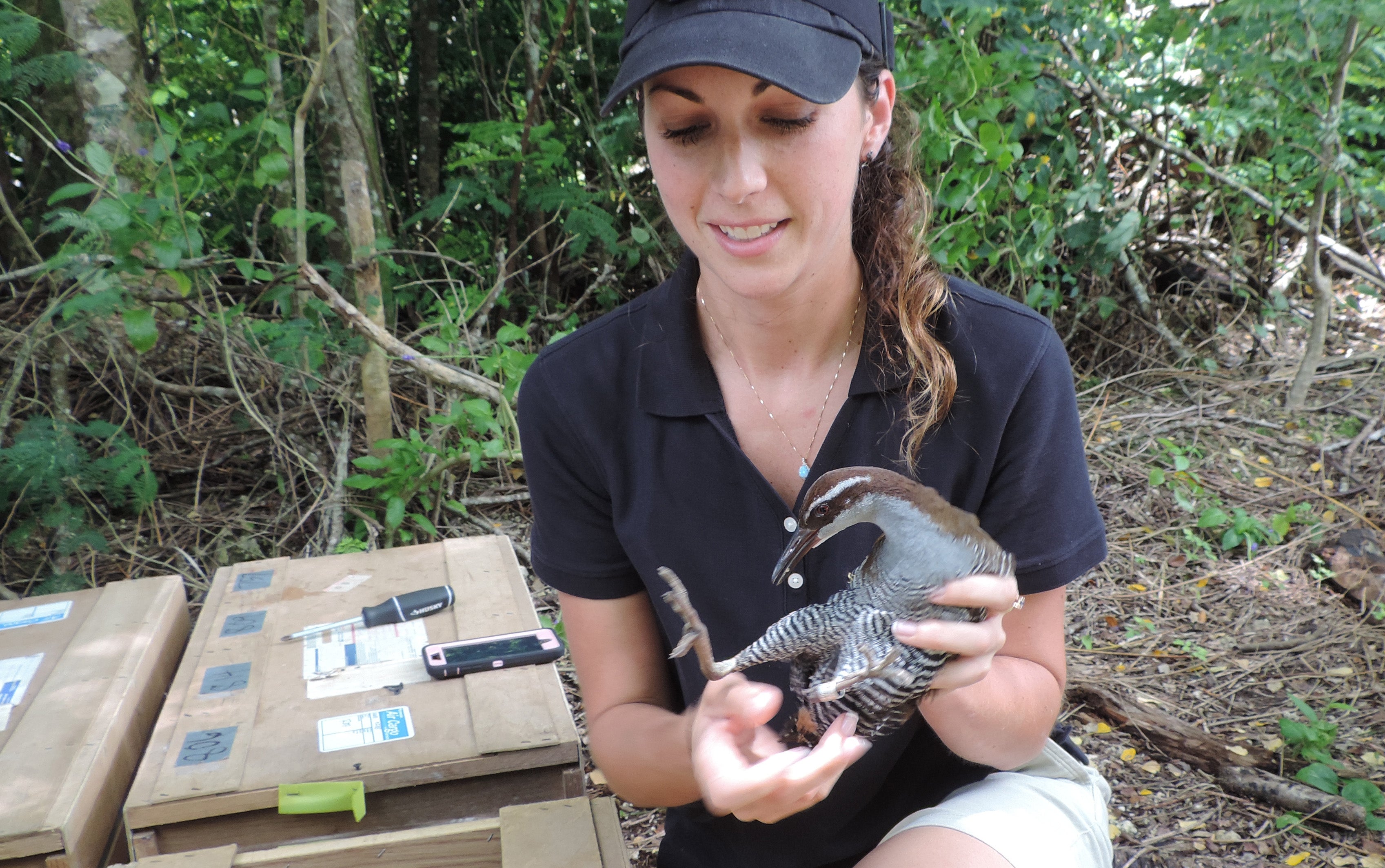

In 2017, Will Pitt, deputy director of SCBI, and I traveled to Rota to participate in the release of 49 birds, two of which were hatched at SCBI the previous year. These two birds were special for me. They were the first Guam rails to hatch at SCBI since I began my career there.

As an animal keeper, I have the privilege of working with some of the most endangered animals on the planet, but its not very often that I have the opportunity to help reintroduce an endangered species to the wild. There are no words to explain how rewarding it is to see my job come full circle as the Guam rails that I had bred and cared for at SCBI took off running into the wild.

While on Rota, we also conducted callback surveys where we played Guam rail vocalizations and waited for responses from the birds. I was hopeful that we would at least get some vocal responses, but I was doubtful that I would have the chance to see a wild Guam rail. However, the birds not only responded with their loud shrieks, whistles and kip vocalizations — a few even peeked out of the grasses. It was the first time I had ever seen a Guam rail in the wild, and it certainly was a surreal experience.

Though it may seem like 200 Guam rails in the wild is not very many, they symbolize hope for the species. The effort to save them is far from finished. Guam DAWR, SCBI and other recovery program participants continue to work with the 170 birds still in human care to hatch more chicks that will be candidates for release on Rota and Cocos Islands.

Their offspring could one day help repopulate Guam, if scientists are able to permanently eradicate the brown tree snake from the island. Guam rails have come a long way, so I’m optimistic that they will return home again.

Related Species: