Lessons from the Swift Fox: Risk, Stress and Success

When you think about your personality, what traits come to mind? Are you bold, willing to take risks or outgoing? Or are you more shy, cautious about trying new things and introverted? Most of us have probably noticed behavioral differences in our fellow humans, or perhaps even in other animals. It turns out that, like people and pets, wild animals show personalities too! In fact, scientists use terms like “bold” and “shy” to describe animals that vary in their level of risk-taking, neophobia (fear of new things) or social behaviors. These differences matter for an animal’s survival and reproduction.

Outward differences can be easy to spot with the naked eye, but animals (including humans) also differ hormonally. For example, stress hormones like cortisol can differ a lot between individuals—some get stressed much easier than others. We often think of stress as the “fight or flight” response because it helps us cope with routine, as well as unpredictable situations. But how do we measure hormones? Wild animals, especially rare ones, can be difficult to find, let alone to capture and repeatedly draw a blood sample from. Talk about stressful! The solution to this problem is quite simple: poop… and lots of it. I admit that stuffing poop into test tubes can be a lot less picturesque than sitting in the sagebrush with binoculars in hand, watching adorable swift fox pups. But scat samples provide a wealth of information about how an animal is coping with life and handling stressors.

A test tube containing freshly crushed swift fox scat, which researchers will analyze for hormone levels.

Reintroduction: the process of capturing and releasing a wild animal into a place where it went extinct. Reintroductions are major stressors for wild animals not used to humans or captivity. Upon capture, animals must undergo careful veterinary examinations to make sure they are suitable for reintroduction, followed by a pre-release quarantine, transport and then the actual release into their new home. Measuring animals’ hormones can tell us how well they are coping with the whole ordeal. What’s more, different personalities can react differently—in terms of behavior and hormones—to reintroduction. This plays a role in an animal’s ability to survive and thrive after release.

Swift foxes wear radio collars to track their movement as they disperse from their release sites.

And these factors are key to my graduate research on an ongoing reintroduction program for swift foxes at the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation, Montana. I want to understand how personality and hormones are related to each other, and to the survival of the foxes reintroduced at Fort Belknap. Are shy foxes more stressed than bold ones? Do bold foxes move farther abroad to explore their new home? Who are the survivors—the bold, outgoing foxes or the shy, careful ones? Other studies show being bold and taking risks can mean greater access to resources like food, but it can also mean the hunter becomes the hunted… or even roadkill! And, what about stress; can a fox be too stressed? Research shows that too much stress can affect things like immunity, memory and decision-making, a bad combination for foxes dealing with diseases, new surroundings and prowling predators.

So how do we tell whether a fox is bold or shy during reintroduction? I picked the brains of experienced fox handlers and used expert accounts from previous studies to create an ethogram (a list of target behaviors and their definitions) that distinguishes bold from shy foxes. We then recorded things like the fox’s posture, movement and vocalizations. For example, bold foxes might be tense, try to bite personnel or struggle to escape during the veterinary exam (one fox was aptly nicknamed “Mr. Cranky”), whereas shy foxes are usually calmer but more vocal. We also used trail cameras to look at the foxes’ behaviors at the release site and compared how bold and shy individuals spend their time adjusting to their new home.

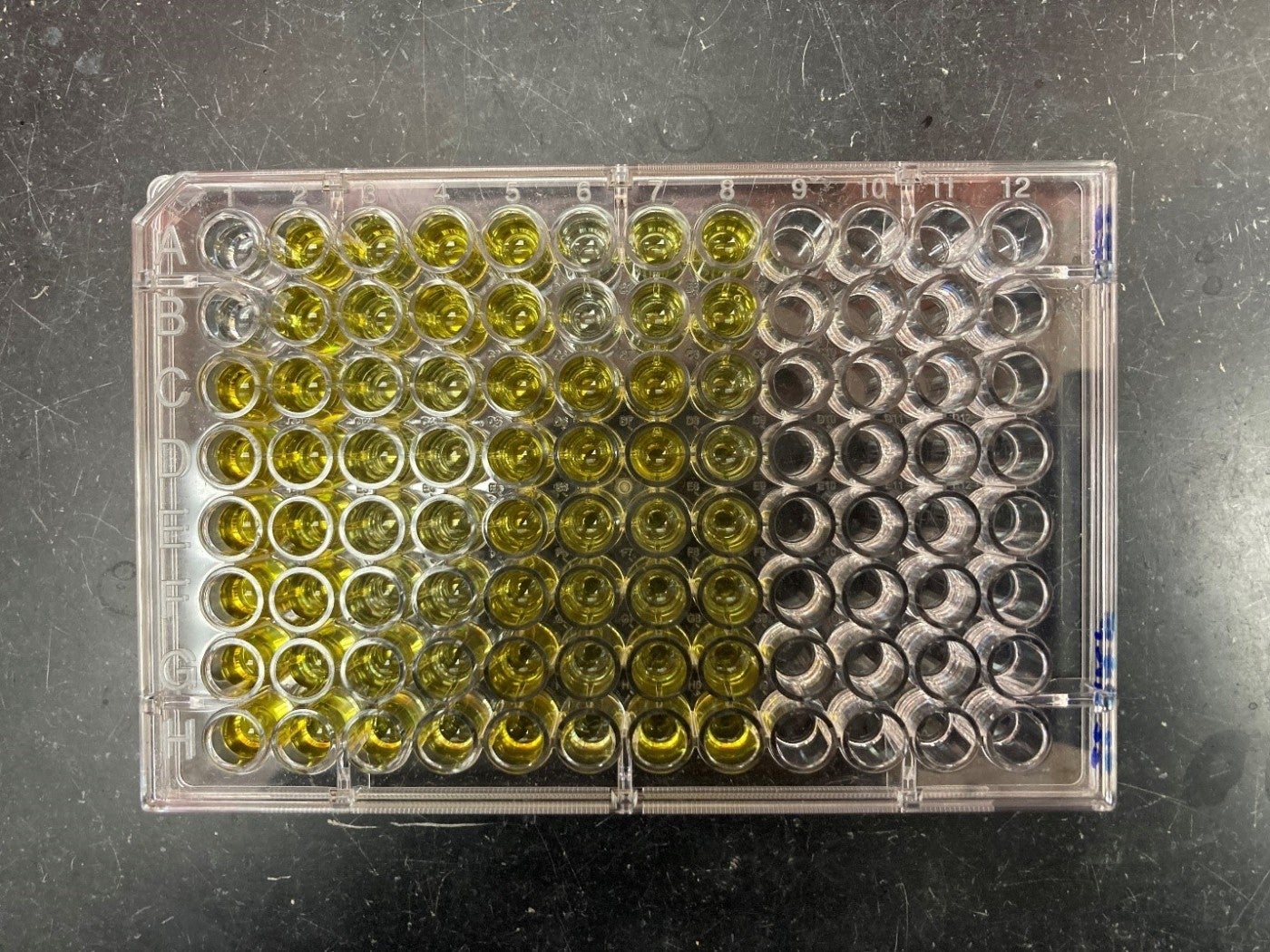

In addition to observing fox behavior, we collected scat to gather information about stress levels and nutrition. We assessed the latter by looking at an animal’s thyroid hormones (an indicator of nutritional status), which help it deal with nutritional emergencies like starvation. Back in the lab, I spent long days crushing poop, shaking poop and doing fancy chemistry with poop, all of which culminate in this beautiful plate endocrinologists (hormone experts) call an “enzyme immunoassay” or EIA. An EIA measures the hormone levels in a sample.

Scientists use enzyme immunoassays, like the one above, to measure stress hormone levels in swift fox scat.

What have we learned so far? Early results suggest personalities and stress hormones differ between foxes captured from healthy populations in Wyoming and Colorado. Specifically, foxes from Wyoming showed bolder behaviors than foxes from Colorado. Wyoming foxes also had lower stress hormone levels on average, based on samples collected at the release site. We are exploring how these differences relate to the foxes’ thyroid hormones, movements and survival after release.

Reintroductions are risky business! From field to lab, we are striving to uncover the secrets of swift fox reintroduction success by profiling the behavior and hormones of the survivors. This will help us create a tool for biologists and managers to carefully select animals with adaptive behavioral and hormonal traits for future reintroductions. Studying what makes an individual fox tick is one piece of a larger puzzle, as we are also exploring genetics, diet and how Fort Belknap’s swift fox population is using the landscape. Maybe these lessons about risk, stress and success will even teach us something about ourselves.

The swift fox reintroduction program is a partnership with the Fort Belknap Indian Community, Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, Defenders of Wildlife, American Prairie, Wilder Institute Calgary Zoo and World Wildlife Fund. Foxes are selected for translocation from healthy populations in the states of Wyoming and Colorado, where wildlife authorities are also lending their expertise in support of this program. Graduate students with George Mason University and Clemson University contribute to the ongoing monitoring and management of the reintroduced swift fox population.