Working Toward Swift Fox Reintroduction

I love living in Montana, and I love conducting research in Montana. You could say I landed my dream job. When I first moved here from Israel, I was overwhelmed by the beauty of such a pristine place, so rich with wildlife and open space. However, reading Lewis and Clark’s famous journals I quickly learned that due to over hunting and land-use changes only a fraction of the wildlife that once lived on the prairie remains. I know we can’t go back in time, but I do think that we can restore the abundant populations of wildlife that once existed on these landscapes to some degree.

My research is focused on understanding the Northern Great Plains grassland ecosystem, and my work focuses on restoring its native flora and fauna. Species reintroductions (bringing back animals that once lived in an area but no longer do), can be an important tool in restoration efforts. We cannot reintroduce every species that once lived here, but we can certainly try to bring some back. In previous articles, I focused on bison reintroduction and the research behind it. Today, I want to talk about a new reintroduction project that I am really excited to start.

Over the last year and a half, I have been working with the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation Fish and Wildlife department head Herold Main and office manager Cheryl Fetter to establish a swift fox (Vulpes velox) reintroduction project to the reservation and the region. The Fort Belknap community has led conservation initiatives in the region for years and is considered, for example, a beacon of success in the effort to help black-footed ferret populations recover. So, we are excited to work with the community on this reintroduction, as well as other contributors to the project, including Defenders of Wildlife, World Wildlife Fund, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, state and federal agencies from Montana, Wyoming, Kansas and Colorado, and other swift fox and reintroduction experts. Together, we form the team that will work to reintroduce swift foxes to Fort Belknap.

Fort Belknap Indian Reservation is located in the homeland of the A’aniiih and Nakota tribes. The Reservation was established by the U.S. government in 1888, and comprises 675,147 acres. This territory was historically shared by a host of native wildlife species, such as wolves and grizzly bears. Some animals, like pronghorn, mule deer, badgers, coyotes, red foxes and bobcats, still share this land today. However, by the late 1960s swift foxes had been wiped out from the region.

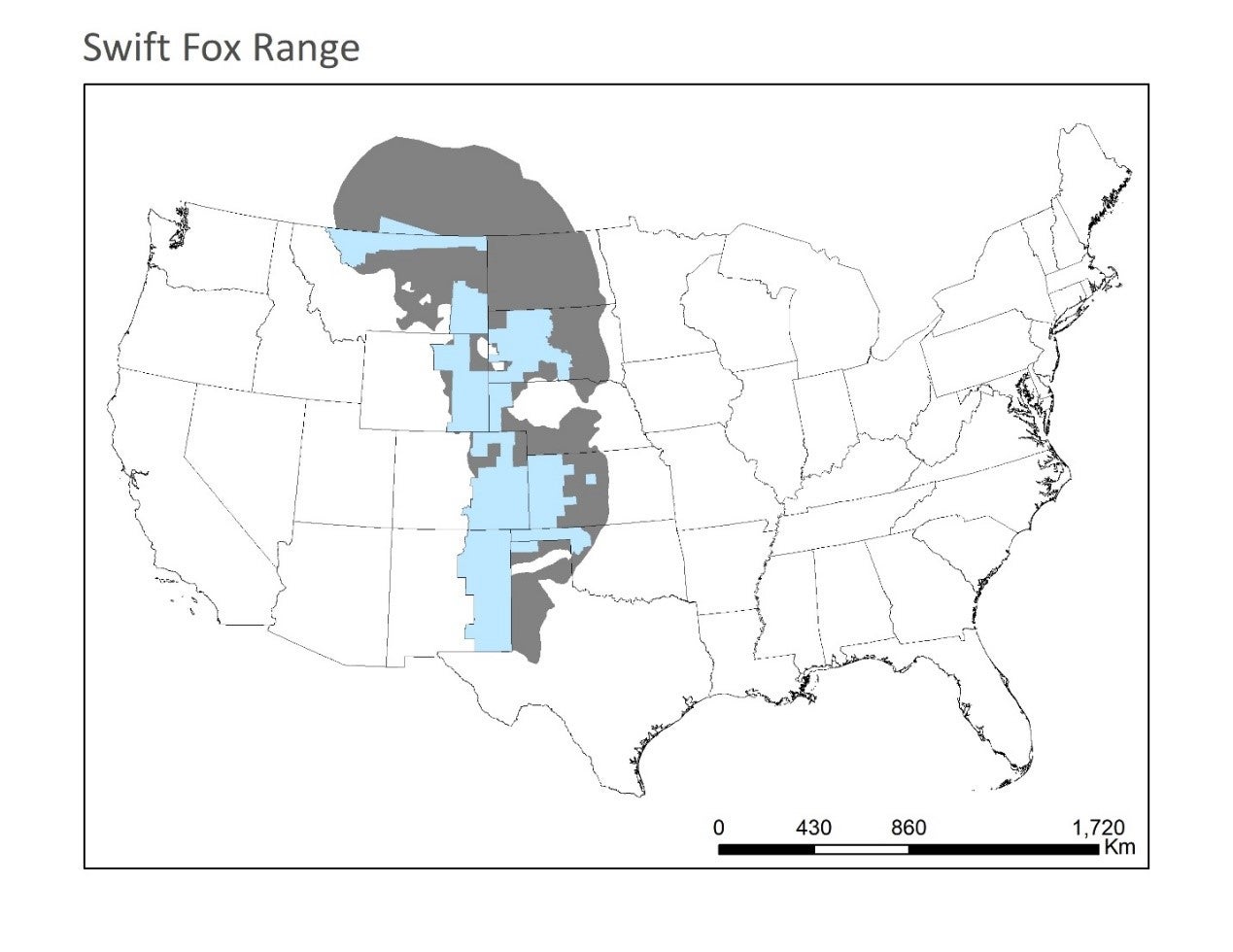

Swift foxes have since returned to parts of Montana but are currently split into two populations separated by a gap of about 200 miles. The northern population is found near the Canadian border and the southern population near the Wyoming border. The members of Fort Belknap Indian Community are interested in reintroducing swift foxes, both for their cultural significance and for the opportunity to reestablish a connection between these two populations.

Get to know the Swift Fox

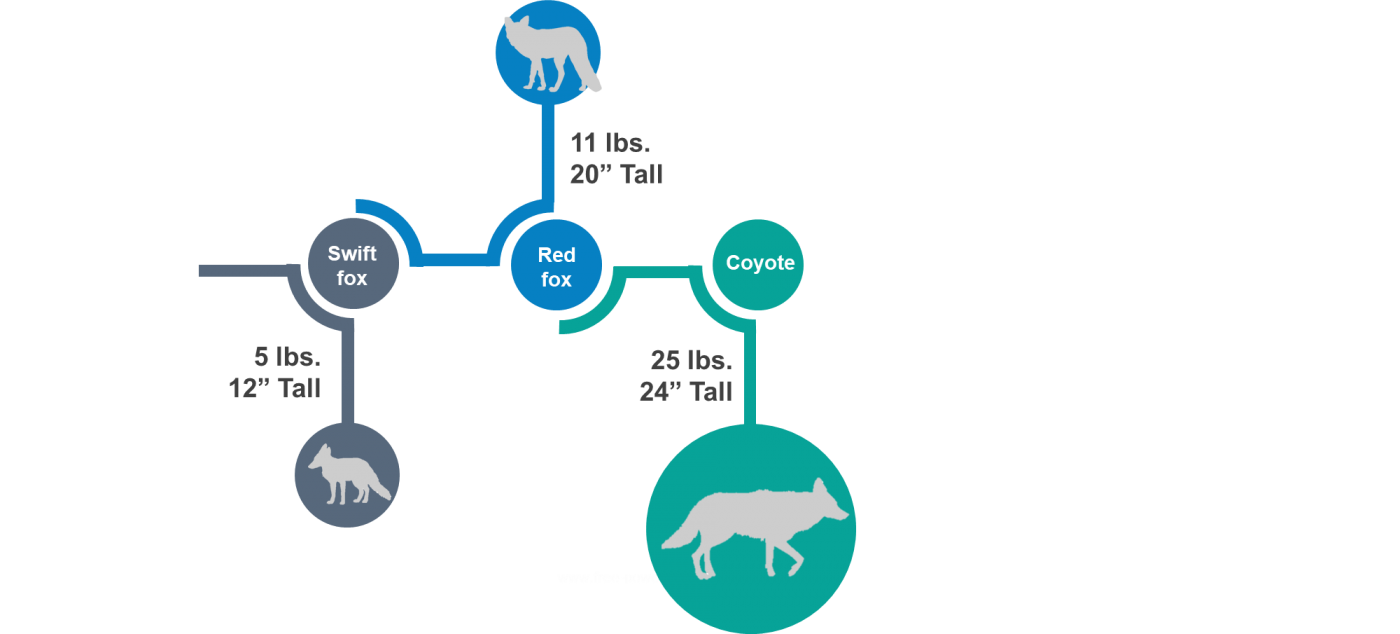

Swift foxes are short/mid-grass prairie specialists. These small carnivores are about the size of a house cat — smaller than their plains neighbors, the red foxes and coyotes.

They mostly eat small mammals (like rodents and rabbits), as well as insects, birds, dead animals and occasionally plants. These foxes are mainly monogamous, with pairs forming in February, mating in March and rearing three to six kits from May through August. Historically, swift foxes lived in North America’s prairies. By the late 1800s and early 1900s, their populations had dropped to 5% of their historic range, mainly due to unintentional trappings and poisoning intended for coyotes and wolves.

Swift foxes were declared extinct in Montana in 1969 but could still be found in the southern U.S. Conservationists successfully reintroduced them to Blackfeet Indian Reservation in northwestern Montana in 1998, as well as to Canada from 1983 to 1991. The foxes also made it back to northern Montana in the early 2000s, but they live in a specific region north of the Milk River. We know that these foxes rarely cross the river, because agricultural practices in the region create unsuitable habitat.

A train can be seen passing through agricultural areas along the Milk River.

If any swift foxes do live south of the river, it is unlikely that there are enough of them to establish a reproducing population. The Fort Belknap Indian Reservation is situated just to the south of the Milk River. We hope to reintroduce swift foxes here through coordinated release efforts known as “translocations.” In other words, we want to move swift foxes from one area to another. We hope to move 40-50 foxes per year.

Before any reintroduction is carried out, there are several steps we have to take to determine if it is even possible. We followed the IUCN’s guidelines for this process. First, we looked at the entire landscape to make sure that there is enough food for the foxes to eat and enough places for them to live. Swift foxes choose to live in flat landscapes with short-grasses and soils that can be easily dug for burrows, which they use for shelter.

Next, we sought expert advice on how many foxes we would need to release each year in order to ensure a healthy population. We also read a lot of studies and papers on prior fox reintroductions to learn what worked (or didn’t work) for others.

Finally, we presented the results of these research efforts to a group of swift fox experts, including wildlife biologists and researchers, as well as representatives from American Indian tribes, state and federal agencies and local NGOs. Following a discussion of the research results, we worked with this group to set the reintroduction plan, goals and budget.

We are now waiting for the final permits from the states where we plan to capture swift foxes. If all goes well, we will start the translocations in late summer 2020. Stayed tuned for updates.