Coral Spawn Australia

This update was written by Virginia Carter, a Smithsonian coral biologist with the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology

During the second week of November, at the start of summer in Australia, the Great Barrier Reef was thriving with new life. As part of the Reef Recovery Initiative, Smithsonian scientists Dr. Mary Hagedorn, Mike Henley and I visited the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS). Along with our collaborator, Rebecca Hobbs from the Taronga Western Plains Zoo, we were able to use human fertility techniques to help Australia ensure their coral populations for many years to come.

Corals brought in from the Great Barrier Reef await their turn to spawn in tanks at the Australian Institute of Marine Science. Photo by V. Carter

This was our fourth year visiting AIMS during the annual Great Barrier Reef spawning event. AIMS is a world class facility that gets better each year; last year they opened their state of the art Sea Simulator.

Our coral work is time sensitive, so rather than going out to the reef ourselves, AIMS scientists bring coral colonies to the lab where they spawn in tanks. Once the coral spawn, we go to work assessing the health of the sperm - just as you would see at a human fertility clinic -examining sperm number and motility (how well they are swimming).

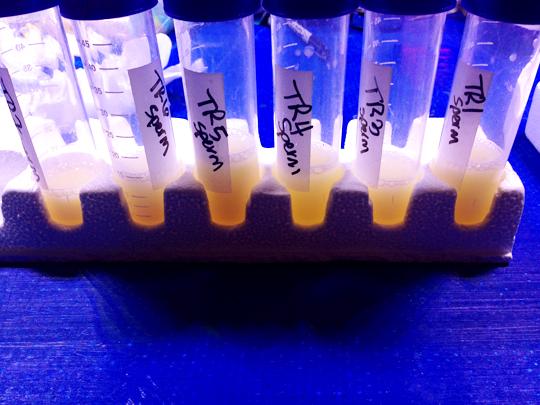

Sperm collected from several coral colonies waits in tubes to be assessed. Photo by V. Carter

After choosing our healthy sperm samples for each species of coral, they are pooled together and we cryopreserve them. This means we freeze the samples at a very specific rate and then they are held at extremely low temperatures. Our samples are kept in the frozen bank at the Taronga Western Plains Zoo and should be viable to use for hundreds or even thousands of years.

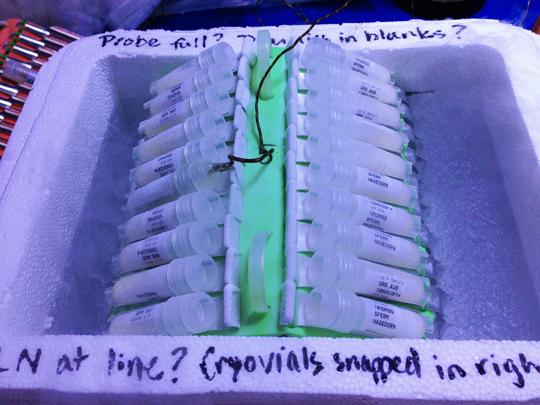

Tubes of sperm are frozen at a specific rate to ensure viability. They will be banked for as an insurance population. Photo by V. Carter

We banked five species this year, which increases the genetic diversity of species already in the bank, including one species that was new*. This brings our Australian species count to seven and the Reef Recovery Initiative's total count to 11 species from around the world (including Australia, Hawaii and the Caribbean).

Aside from banking, one of our big goals this year was to raise corals that were created using sperm that was previously frozen.

Mary Hagedorn examines coral embryos that were fertilized with cryopreserved sperm.

Henley will be at AIMS until late December and will care for the larvae that we created. He will help to ensure their survival and coordinate with AIMS scientists to continue their growth once he leaves. This year there was the possibility of a split spawn event, meaning that while there's usually one large spawn - at the time of the full moon during the beginning of the Australian summer – there could be two smaller spawn. The split spawn will allow Henley to create even more coral from frozen sperm during his remaining time there. This will increase our chances that some of our coral will make it to adulthood.

Mike Henley counting coral larvae that have settled onto tiles in tanks. Photo by B. Hobbs.

In addition, Hobbs, a reproductive biologist, is developing techniques to culture single cells derived from 4 and 8 celled embryos. Freezing single embryonic coral cells will allow us to grow coral without the added need for eggs and a fertilization step. This work is ongoing, but progressing.

We are happy that this trip was successful and that we are able to continue to help Australia add to their frozen repository of coral species. Hopefully we will have some pictures of growing corals in the next few months.

The coral species currently banked are:

- Acropora hyacinthus (new this year)

- Acropora tenuis

- Acropora millepora

- Acropora loripes

- Goneastrea aspera

- Platygyra daedalea (banked in 2012 and 2013)

- Platygyra lamolina (banked in 2012)