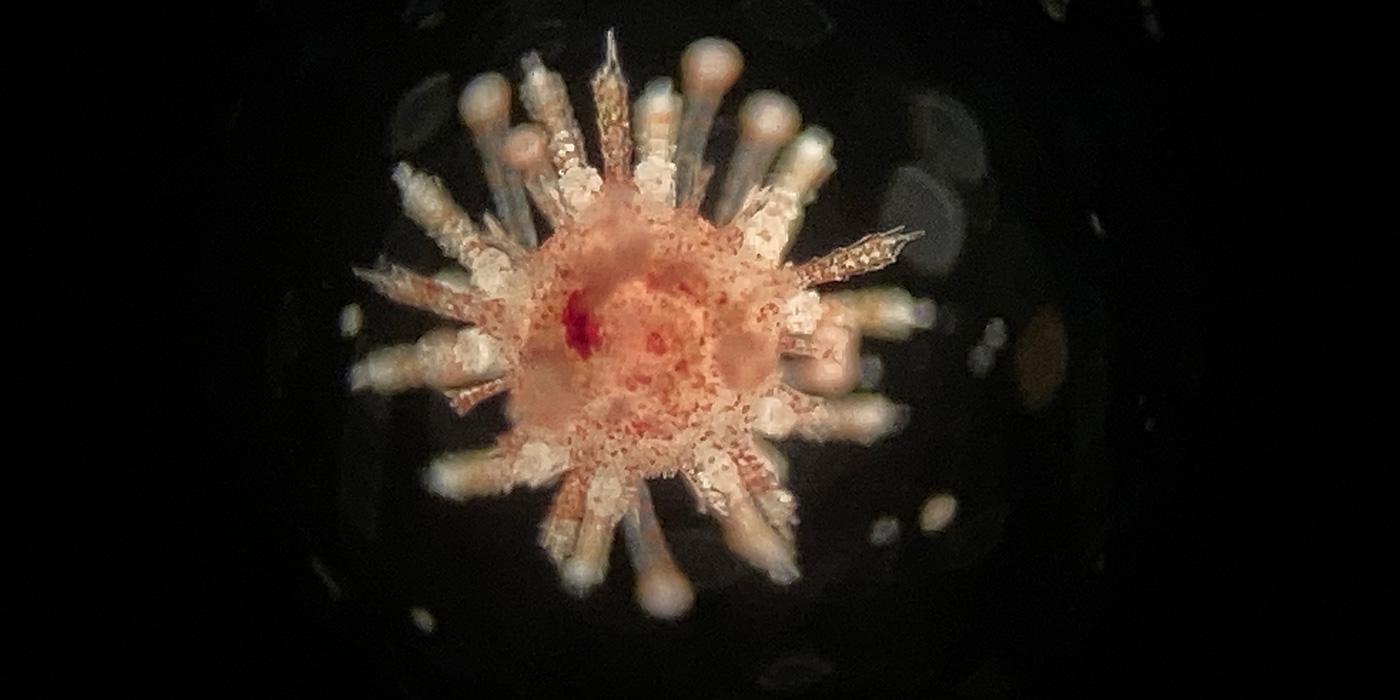

Five Fascinating Facts About Coral

1. Coral Are Brainless

A colony of mushroom coral.

Although they may look more like interesting rocks, corals are animals! Corals are invertebrates (animals without a backbone) and belong to the phylum Cnidaria, along with sea anemones, sea pens and jellyfish. Corals are technically individual polyps, which divide into genetically identical polyps to create a colony. Like other species within Cnidaria, individual coral polyps don’t have a brain. Despite their lack of brains, coral colonies can coordinate spawning periods and time their release of sperm and egg cells to reproduce.

2. Not All Corals Build Reefs

Elkhorn coral, like this one found in Curacao, are a type of stony coral and feature a strong calcium carbonate skeleton.

There are many diverse species of corals in our oceans, living in both warm and cold waters, from the shallows to deep ocean trenches. They range from rock-like creatures to mushroom-looking disks and some even have tentacles! However, reef-building or stony corals only live in shallow tropical and subtropical waters. Stony corals create a skeleton of calcium carbonate to create the hard structure most people recognize as “coral.” These skeletons stay put, even when the coral polyps themselves die. New coral polyps grow atop the dead polyps, forming new calcifications. This allows for expansive reefs to form, such as the Great Barrier Reef of Australia.

3. Corals Are the Unsung Heroes of the Animal Kingdom

Reef-building whisker coral can be found in Amazonia, along with more than 26 other species of Anthozoa.

When we think of ecosystem engineers, or species that drastically alter the landscape and provide habitat for other animals, we often think of mammals such as bison or beavers. But stony or reef-building corals are some of the most significant ecosystem engineers in the world. Coral reef ecosystems are believed to support roughly 25% of known ocean species. They provide both permanent homes for reef-dwelling species, as well as temporary, nursery-like areas for juvenile marine life.

4. Corals’ Biodiversity Boon Is Good for Humans, Too

Reefs, like this one in Curacao, are home to many species of marine life.

Coral reefs rival rainforests in terms of biodiversity, yet they cover less than 0.1% of the entire ocean. Despite their relatively small geographic footprint, coral reefs provide massive ecosystem services to humans. They protect our shorelines from eroding, purify carbon dioxide from our atmosphere and are even used in cement production. Many modern medications derive key ingredients from marine life connected to coral reefs, including treatments for asthma, cancer and HIV. Plus, tourism and commercial fishing industries rely heavily on coral reef ecosystems. Economists have estimated coral reefs add more than $300 billion annually to our global economy.

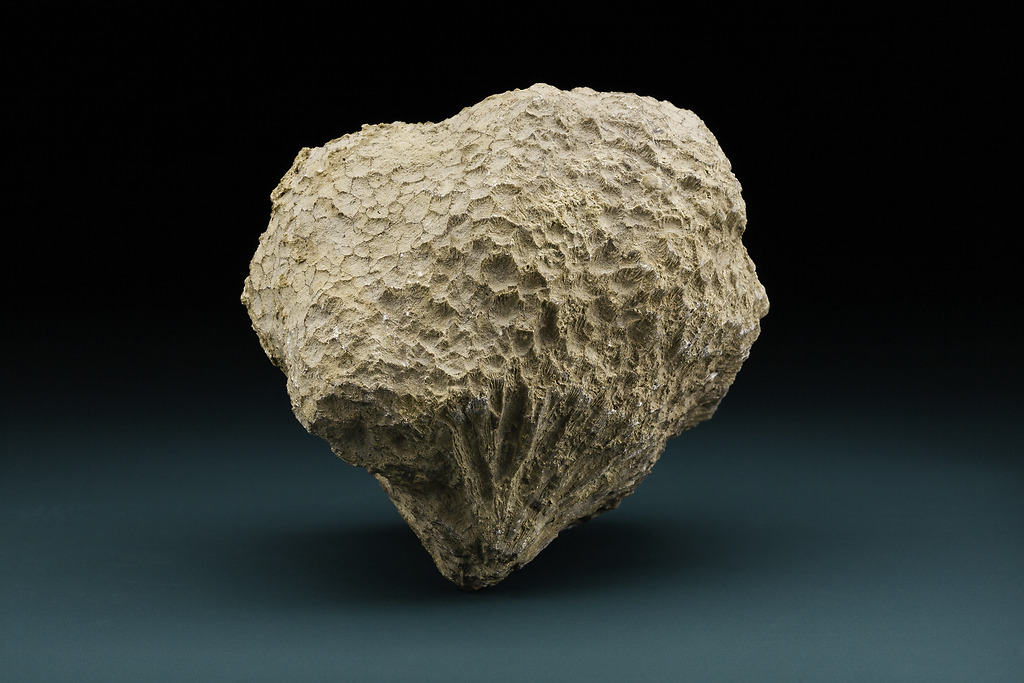

5. Corals Are Ancient

A fossilized colony of rugose coral, which is believed to have gone extinct more than 250 million years ago. Courtesy of Chip Clark, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

While their ancestors’ fossil record extends back 550 million years, the first true corals appeared during the Cambrian period, roughly 540 to 485 million years ago. For some perspective, corals are older than dinosaurs, fish, land plants and even the Appalachian Mountains. Some “modern” species alive today first appeared in the middle Triassic period, which was around the time the first dinosaurs started to roam the earth. While we aren’t sure how long individual coral polyps live, it is estimated that most current reefs are between 5,000 to 10,000 years old. But some reefs date back 50 million years!

A comparison of healthy coral (left) and bleached coral (right).

Even though they survived hundreds of million years of ecological changes, corals aren’t adapting fast enough to survive in our rapidly changing world. Climate change, pollution, over-fishing and rising oceanic acidity levels are killing corals. Today, 10% of all coral reefs have been destroyed and more than 30% have been seriously degraded. The good news is: Smithsonian scientists are working to save corals and our oceans at large! Senior scientist Mary Hagedorn and her team have pioneered low-cost, high impact reproductive technology to reduce the impacts of climate change on coral populations, primarily via cryopreservation of species around the world. The team has also utilized assisted gene flow to promote genetic diversity of coral species in the Caribbean. They are even training conservation professionals around the world to preserve coral species in biobanks to broaden the scientific community’s ability to save corals.

You can help corals, too! Reducing the number of single-use plastics you purchase, limiting pesticides used in the home and cutting back on your use of fossil fuels are all small ways to make ocean-friendly choices in your daily life. For more ways to protect our oceans, visit oceans.si.edu.