Making Sense of Animal Milks

You might be surprised to see someone walking around the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in a full-body snowsuit. But as a research assistant for the nutrition laboratory, I wear a snowsuit year-round — even in the summer when an average day in D.C. is 93 degrees and humid. That’s because I spend a lot of time in a -20 degree Fahrenheit walk-in freezer located in the Zoo’s science building.

I love animals and have always cared about conservation. While pursuing a degree in biology and environmental studies, I was fortunate enough to intern at the Zoo’s nutrition lab. I studied One Health — the concept that human, animal and environmental health are all interconnected — and found my passion in zoo nutrition. Today, I’m a full-time scientist at the Zoo, where I spend a lot of time in a not-so-ordinary freezer.

This freezer is home to the largest milk repository in the world, with samples from 183 species dating back to the 1980s. I’m sometimes in the freezer for up to four hours a day, so the snowsuit is a requirement (I make sure to pack wool socks, too).

We store milk from armadillos, bats, lions, seals, elephants and pandas — just to name a few. Samples are shipped here from all over the world and kept cool with dry ice during long journeys. We have milk from California, Europe, and (of course) from right here in Washington, D.C.

A second, smaller freezer stores even more samples of milk.

If you’re wondering how we collect milk, the answer is that it’s different for each animal. Keepers have trained some of the Zoo’s primates — including western lowland gorilla Mandara and orangutan Batang — to voluntarily provide milk samples. For armadillos, we use a pseudo breast pump. For some ungulates (or hoofed animals), it’s just like milking a cow.

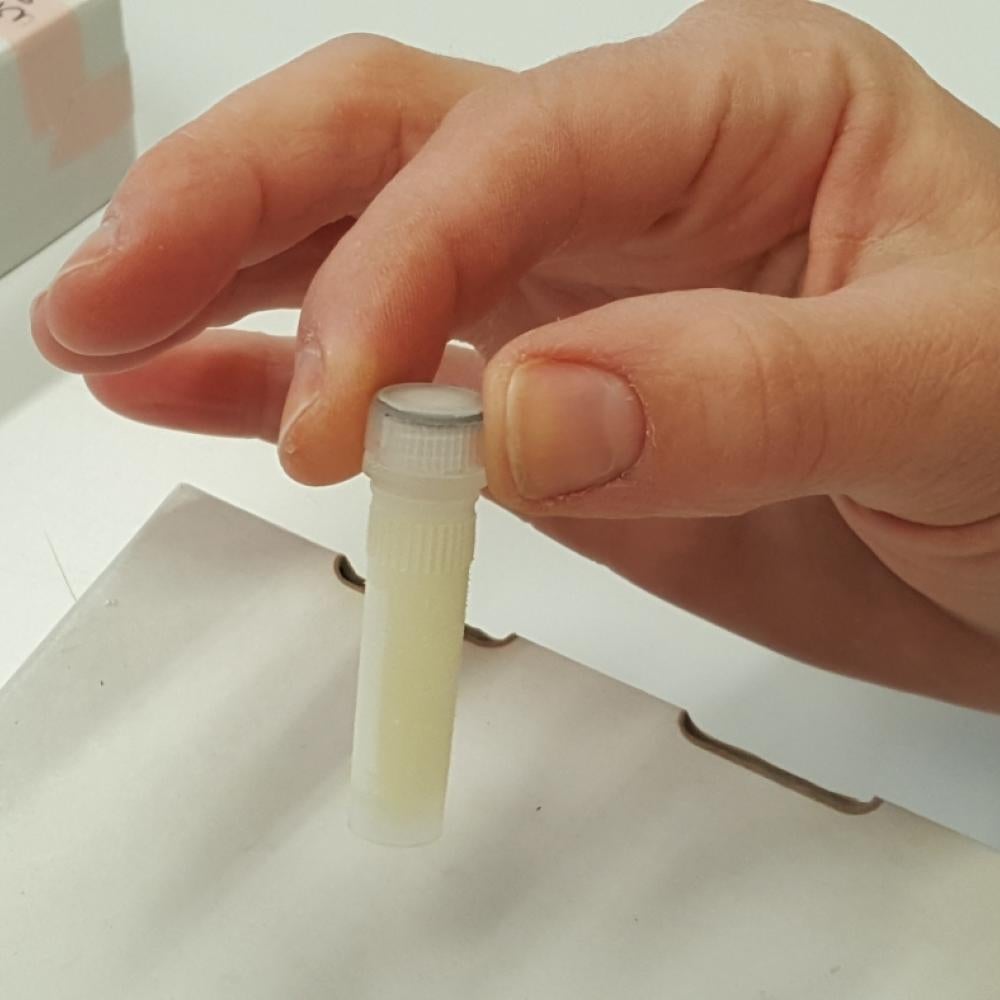

Not all milks are alike. You can tell the difference between some of them simply by using your senses. Some milks smell fishy — like samples from sea lions and whales — because of what those animal moms eat. Some are as yellow as cheddar cheese or white like provolone, and others can be clear. This color variation is usually due to the amount of fat and nutrients in the milks.

In the nutrition laboratory, we focus on these nutritional differences. There are three primary nutrients that we observe in milk: fat, sugar and protein. Do you think whole milk is fatty? Whole cow’s milk is a measly 3% fat, whereas an orca’s milk is 30% fat!

You can tell the difference between some milks simply based on their color, texture and smell.

We use these milk samples for clinical and research purposes. They can help us understand evolutionary trends in mammals, because the nutritional composition of milk can be similar among animals that are related. For example, we’ve learned that animals in the superorder Xenarthra — sloths, armadillos and anteaters — all have high protein milks. We can also analyze a milk sample and create a similar formula to feed a baby animal. Cincinnati Zoo’s baby hippo Fiona is perhaps the most famous recipient of a formula that we helped create.

It’s great to be able to provide supplemental milk when an animal mom can’t, but there’s still so much more to learn about what’s in milk and why. In fact, we’re working with the Zoo’s genetics lab to learn about the microbiomes found in milks.

A microbiome is a community of bacteria that exists in a specific area. Remember, not all bacteria is bad. For example, humans have a gut microbiome which is very important for our digestive health. To determine which microbes are present in a sample of milk, we use DNA sequencing.

DNA sequencing is the process of identifying the sequence of nucleotide bases in a piece of DNA. Think of these as the chemical building blocks that make up a piece of DNA (the order of those building blocks is a sequence). Once we’ve sequenced DNA from a milk sample, we can use a series of data analyses and reference databases to interpret those strings of nucleotides and match them with a microbial taxon (or group).

For a long time, scientists didn’t have the resources to efficiently and accurately analyze the world of microbial communities. DNA sequencing was a long and tedious process, because technology only allowed scientists to read one section of DNA at a time. Now, geneticists can sequence an entire genome (an organism’s complete set of DNA) all at once. This easier and remarkably faster method of sequencing DNA makes studying milk microbiomes much more achievable.

We use milk samples for clinical and research purposes. They can help us to understand evolutionary trends in mammals or to create the best formula to feed a baby animal.

Still, not much is known about the milk microbiome yet, except that it exists. Finding trends or relationships among the milk microbiomes of mammals could help us understand their purpose, like whether the milk microbiome helps form the gut microbiome. Learning more about how the gut microbiome develops could help us resolve digestive problems. For example, we may discover that there is a benefit to adding certain probiotics to milks for baby mammals when creating formulas.

See what I mean when I say there’s still so much more to learn about milks? My coworkers will have to continue to endure the swoosh swoosh of my snowsuit down the hall, because I don’t plan on packing it up anytime soon.

Guess That Milk!

Now that you’re a milk maven, see if you can match some of the milk samples to the animals they came from.