From the Field: Bird Banding on Texas’ Gulf Coast, Chapter 1

In March, a team of Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center scientists traveled to Texas to study birds that travel through the Gulf of Mexico. The following is an update from the field, written by SMBC research technician Tim Guida.

On March 11, our crew of SMBC scientists arrived in Matagorda County to begin the seventh year of migratory bird banding on the Texas coast. Once again, we would be setting up nets at The Nature Conservancy’s Clive Runnells Family Mad Island Marsh Preserve, which contains a beautiful mix of coastal prairie, marshy sloughs and scrubby woodlands.

We were happy to see that the habitat survived Hurricane Harvey remarkably well, and we arrived to find that our net lanes had already been cleared by a dedicated group of preserve volunteers. Grateful for their assistance, we were able to get right to work placing our nets and monitoring birds.

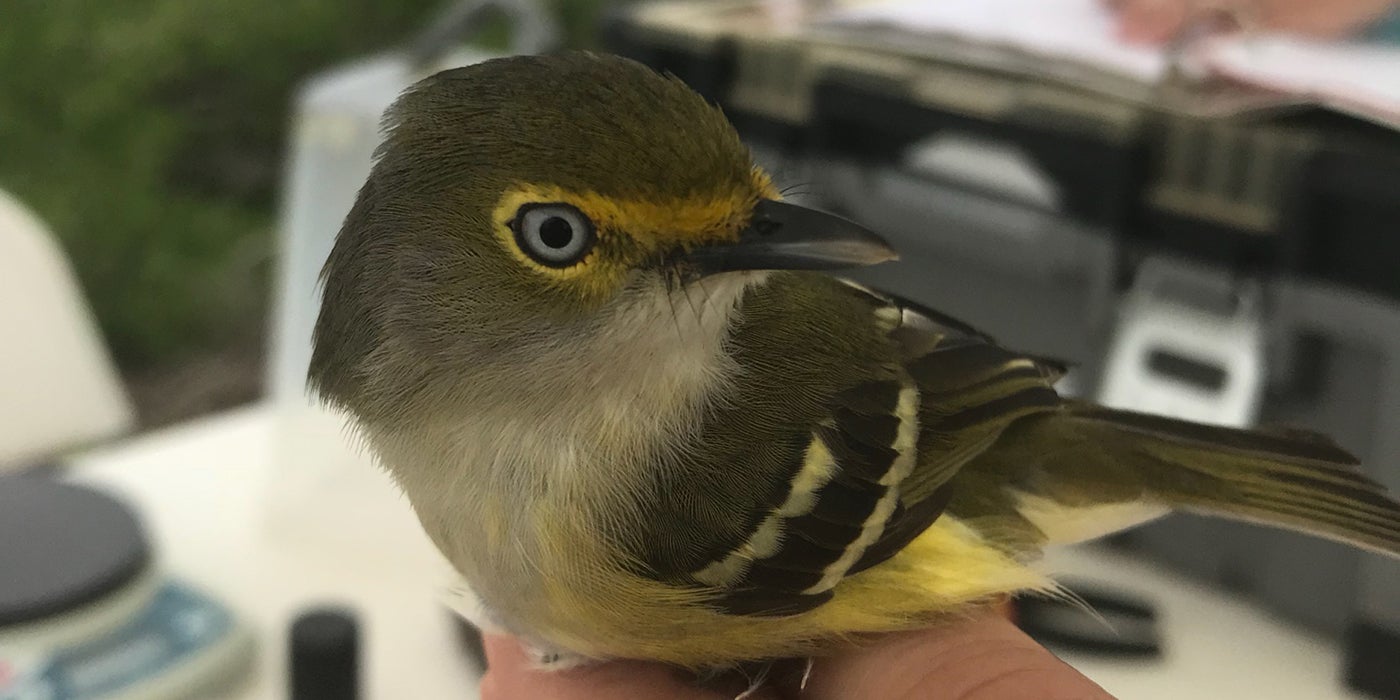

Our first capture of the year (though non-migratory) was, appropriately, Texas’ state bird — the northern mockingbird. Some of the migratory birds captured during the first few days included swamp and Lincoln’s sparrows, yellow-rumped and orange-crowned warblers, white-eyed vireos and gray catbirds.

Most of these birds probably spent the winter at the preserve, and a few even wore bands from our previous seasons. We also captured a long-billed thrasher — a bird of southern Texas and northern Mexico, which is near the northern end of its range here. This is only the second time we have captured a long-billed thrasher at Mad Island. The first was caught and released in 2014.

Within the first week, some of the earliest long-distance migrants arrived. Prothonotary warblers are always a highlight, as are the more subtle Louisiana waterthrush. Hooded warblers are also a stunning early migrant.

By arriving in the earliest days of spring, we are lucky enough to witness the seasonal transition from winter. The trees are just beginning to bud, and few flowers are seen. But within a week or two the Texas sun quickly brings out the leaves, and spring rains lead to an abundance of wildflowers. Just as birds begin to arrive, the habitat is flush with green and buzzing with insects, providing much needed food for the hungry migrants.

To read the second part of this field update, click here!