Texas Shorebird Expedition Blog

Unlocking the Secrets of Bird Migration

The Smithsonian's National Zoo posted the below video on their channel about the the Texas shorebird project.

This video was made possible with the support of ConocoPhillips.

Laguna Madre: a Shorebird Spectacle

A needle in a haystack is defined as something that is very hard or impossible to find. As you may have read in my previous blog, this is exactly the type of mission I was on last week. And sure enough, finding the 29 birds with transmitters out of the near million birds I saw was very hard, if not impossible.

During the week I was on Padre Island, a strong frontal system brought winds from the southeast. This created unfavorable foraging conditions on the beaches but favorable conditions on the backside of the island, which is how I ended up trudging along mud flats instead of sunning on beaches. Additionally, previous radio telemetry studies in this area have highlighted a particular area on the backside of the island, the Laguna Madre, as an important foraging area for shorebirds during this time of the year.

Our footprints in the exposed mudflats of the Laguna Madre, Padre Island National Seashore. Photo by David Newstead.

Access to this area on the Laguna Madre is very difficult but finally we made it. As David Newstead, of Coastal Bend Bays & Estuaries, and I began our trek across the Laguna Madre, he marvelled at how he had never seen so much of the Laguna exposed at this time of the year, creating lots of productive habitat for shorebirds. As the saying goes, if you build it they will come, and come they did.

As we looked out across the horizon, thick clouds of birds were visible all around us. Through the spotting scope we saw a landscape littered with hundreds of thousands of shorebirds. It was incredible! Like nothing I have ever seen. Even David, who has witnessed many shorebird migrations, was excited. We stood paralyzed with amazement not knowing where to begin or which direction to walk. All we could do was stare at the spectacle before us.

Shorebird flocks flying over the Laguna Madre, Padre Island National Seashore. Photo by David Newstead.

But reality sunk in and we realized we had a job to do: find six individual red knots in close to a million birds. You might ask how you even begin something like this. I asked myself the same thing!

We identified a flock of medium-sized shorebirds and off we went in that direction hiking across the mudflats, sometimes dry and sometimes in water up to our ankles. As soon as we came close to a group, we began to move very slowly almost as one person, hoping not to disturb the thousands of birds before us. Well, sometimes it worked and sometimes it did not. Although it was frustrating when a flock was spooked, it was quite amazing to see that many birds lift off, fly in our direction, and at the last second bank right or left only a few feet in front of us.

Shorebird flocks flying over the Laguna Madre, Padre Island National Seashore. Photo by David Newstead.

This continued for many hours. Hiking back and forth, traversing the Laguna Madre, trying to locate red knots, and scanning the groups with the spotting scope, hoping we could find at least one of our birds. Sad to say, we did not find any of the six red knots or any of the other birds with transmitters. We did however re-sight a few banded piping plovers and 13 banded red knots. Even more exciting, one of the red knots had a geolocator David put on in 2012.

Snack break while hiking across the Laguna Madre, David Newstead and Amy Scarpignato. Photo by David Newstead.

Although it was frustrating not to re-sight any of our birds, I will always remember that spectacular day on the Laguna Madre and the enormous number of shorebirds that rely on this area. It was truly amazing and something that I wish everyone could witness. Not just for the spectacle but if we can visualize and witness something this incredible then it is only natural that we will want to learn more about and protect these special and important places. Check out a video put together by the Coastal Bend Bays & Estuaries Program of our day: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p5zLCsOdpvc.

Shorebirds foraging and flying around the Laguna Madre, Padre National Seashore. Photo by David Newstead.

Needle in a Haystack

Have you ever tried to find a needle in a haystack? Well that is exactly what I am trying to do this week… Sort of.

Scoping out Mustang Flats, Mustang Island.

Last October, Peter Marra, Autumn-Lynn Harrison and myself along with David Newstead of Coastal Bend Bays & Estuaries Program ventured to the Texas Gulf coast to deploy transmitters on red knots, black-bellied plovers, marbled godwits, and long-billed curlews. Learn more about the trip by reading our past expedition blogs.

The birds with transmitters spent their winter here on the sunny Gulf Coast. During the end of March and beginning of April, they will begin their migration to the breeding grounds. Some of the long-billed curlews we tagged, are off already! See the live map of their movements.

But for the next few weeks most of the shorebirds are still here. My mission is to find as many of them as possible; 6 red knots, 14 black-bellied plovers, 9 marbled godwits, and a partridge in a pear tree. Kidding about the partridge!

Many of the tags we used store geographic positions on board the tag. Then, at the end of the tracking period, the positions are sent in a single burst to us via satellite. But we have a long time to wait until we get the data, so for now, we have to rely on our eyes to do the work. We want to make sure the birds are doing ok carrying the devices, and that the tags are in good shape.

"Resighting" birds involves identifying certain individuals by their individualized color bands. This trip began with me driving along beaches with my binoculars trying to spot birds with color bands. But due to unfavorable wind conditions, my luck has changed. I am now forced to the backside of the island, trudging through and sinking in mud flats.

Trudging through and sinking into mud flats in search of our birds. Laguna Madre, Padre Island National Seashore.

I have seen hundreds and hundreds, probably thousands, of wading birds, waterfowl, and shorebirds. I have seen marbled godwits, long-billed curlews, black-bellied plovers, and red knots. I have seen many banded piping plovers. But I have not seen one of our banded birds. Stay tuned and wish me luck, the search continues …

Mudflats, Port Aransas Nature Preserve at Charlie's Pasture.

Curlew Migration Begins

One of the curlews we captured last fall has flown the coop, leaving western Nueces County and trekking up to Abilene! It hasn't left Texas, but has made substantial progress on its journey towards its nesting grounds. Two other curlews we caught last fall on Padre Island, Texas, are getting antsy—I'm guessing they'll be the next birds to go.

In other news, today is the first day we've been monitoring ground-nesting shorebirds on Mustang Island. We were pleased to find the first snowy plover nest of the season at the Port Aransas Nature Preserve, being dutifully incubated by one of the plovers we banded last year.

Other shorebirds are migrating, too. Flocks of American Golden-Plovers were observed and Upland Sandpipers have been heard twittering way overhead. It's spring down here!

Chasing Curlews

Fall is my favorite time of year and it's the eve of Halloween! This year I'm creating a Long-billed Curlew costume. It's perfect—the bird is freakish. It's the Frankenstein of the bird world with a bill bigger than its body.

I realize no one will have a clue about what I am in costume, which is the other reason why it's perfect. I can open their eyes to Curlewmania. They are the coolest birds on the planet and everyone should know about them since they're disappearing, like Halloween ghosts before our eyes.

I am also haunted by curlews after chasing the mutant-like things all over the Texas coast. For the past week, our team searched for curlews, almost night and day, in an attempt to capture eight of them to attach satellite transmitters. We missed bird after bird. They were in a park in downtown Corpus Christi for weeks until we showed up. It was as if they left intentionally.

They teased us on a daily basis, walking near but not into the capture zone of our nets. When we finally netted one bird with a net gun, it wiggled free before we could get to it. I swear it laughed at us as it flew away. They were getting into our heads.

Then came our final day in the field. We captured our quotas of Red Knots (6) and Black-bellied Plovers (11). We even managed one Marbled Godwit (11 more to go)—another remarkable species with a bill that resembles a sword. We wanted the elusive curlew. We found a roost of 190 late in the afternoon on an island not far from the shores of Portland, a small town outside of Corpus. We decided to pull out the BIG cannon net.

Marbled Godwit. © Tim Romano.

It's five times the size of our regular net, requires a giant load of black powder, and uses three projectiles to power it across the enormous capture zone. Confident, we discussed how we would deal with the huge numbers of curlews in our clutches. The curlews were giggling on their mudflats that night thinking about our attempts at capturing them.

We showed up at the boat launch early Monday morning and scanned the island. No curlews. Dejected, we contemplated our next move and calculated the time required to catch our flights. We decided to head to Fish Pass in a state park where we had several close calls catching curlews.

There, we found six curlews sitting in the exact spot where we planned to trap. It took about 45 minutes to set the trap. I twinkled from one direction and David from another. Owen waited with the controls to explode the net over the birds. It took about an hour, but we eventually had five to seven curlews and three godwits in the capture zone. It was the 'bird load.'

David did the count down…3-2-1 Fire! Fire! Fire! Nothing happened. David anxiously whispered into his radio, "We're ready, release…hit the switch." Nothing. We attached the wires from the cannons to the car battery in case it was a power issue. Several curlews had departed but there were still plenty of birds. We fired again but nothing happened. We all stared at the sky and looked in our pockets for our white flags to wave at the curlew in a symbolic gesture of surrender.

But not quite. We still had four hours before departure.

We set up the smaller cannon net, put up two decoys and began twinkling. Within an hour, two curlews were in position and David dug deep into his twinkling playbook. He danced these birds into the middle of the net like I've never seen before. He quietly called for the net, "3-2-1 FIRE."

Curlew decoy. © Tim Romano.

I could see the net explode and the two curlews took flight toward the open water but they were caught in the last two feet of net. They were fast, and it was close, but we finally caught our curlews. We attached the satellite transmitters and released the birds knowing that we would learn an enormous amount about their secret lives.

Long-billed curlew.

Our Texas trip ended, but it really is just the beginning. Now we start learning about the biology of the knots, plovers, godwits and curlews as they send us information about their lives and their migrations across the hemisphere. Stay tuned.

Video showing curlew release.

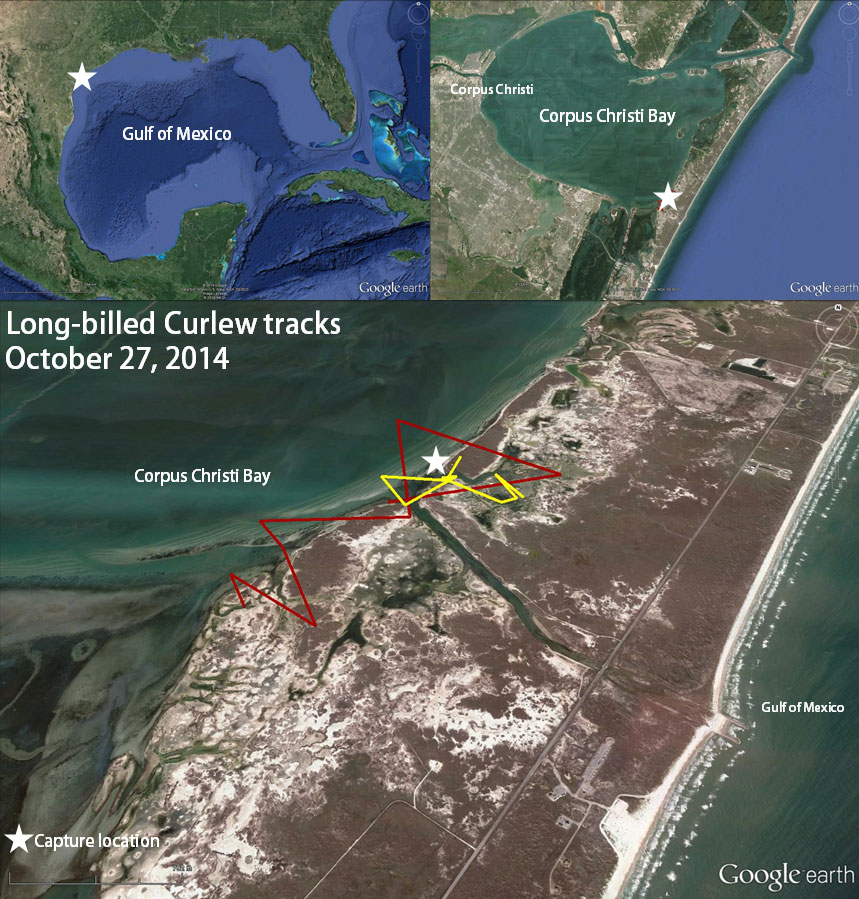

Map showing locations of the two tagged curlews after capture.

Don't Mess with Texas…Beaches

It's the end of a weekend of field work and our expedition is coming to a close. We have successfully deployed transmitters on 11 Black-bellied Plovers, 6 Red Knots, and 1 Marbled Godwit. We have one more day to try and catch curlews and a few more godwits.

Our work this weekend took us to the large and diverse Port Aransas Nature Preserve; to the muddy fishing channels and windy beach habitats of Mustang Island State Park; and to the longest stretch of undeveloped barrier island in the world, Padre Island National Seashore with it's over 80 miles of seashore.

Shorebirds share the beautiful habitats of the Texas coastline with species like ghost crabs, sea turtles and of course people. In fact one of the primary reasons shorebirds have declined globally is because of coastal development and disturbance. Impacts to the beach habitats we visited, especially from plastic litter, beach driving, and fishing bycatch (catching non-target species), were obvious. Equally obvious was the dedication of many locals to protecting and cleaning the Texas coastline.

Crab. © Tim Romano.

Since 1986, 465,000 volunteers have removed 9,000 tons of trash from Texas beaches and estuaries. On Saturday, we met one of these dedicated volunteers on Padre Island National Seashore, walking out collected trash from the beach well after twilight.

It was well after twilight for us too by the time we cleaned up the equipment and packed up Saturday to head in to town. We finished tagging our last red knot and plover late that day. The transmitters we deployed tell the story of a year in the life of these species, critical for understanding where along the way they may be impacted by our actions. Needing a break after long workday, we rounded out the evening at a beachside restaurant with some local country music—featuring a member of our field team on the fiddle!

Owen playing fiddle in his Texas band.

The many people taking the "Don't mess with Texas" slogan to heart in respect of beaches encouraged and inspired us. We share this critical and sensitive habitat with species like shorebirds and it's essential we minimize our impact. Anyone can participate in a local beach clean-up day. To learn more about the world's beaches and oceans, and how you can help protect them, visit the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History's Ocean Portal.

Pictures taken by Tim Romano.

Freebird

After a full day on the beach, faces burned by sun and wind, we were winding down outside on the hotel patio when Lynyrd Skynyrd's Freebird started playing on the Tiki Bar stereo.

If I leave here tomorrow,

Would you still remember me?

For I must be traveling on now

'Cause there's too many places I've got to see.

I'm fairly confident Ronnie Van Zant wasn't thinking about the migratory connectivity of Black-bellied plovers when he wrote this rock classic. But the song rang true to us as we sat being chilled by the evening breeze and reminiscing about the day. Although we blanked on curlews and godwits, we did successfully capture three plovers and deployed a new technology that will allow us to not only remember them when they start traveling on, but to track their specific moves.

Pictures taken by Tim Romano.

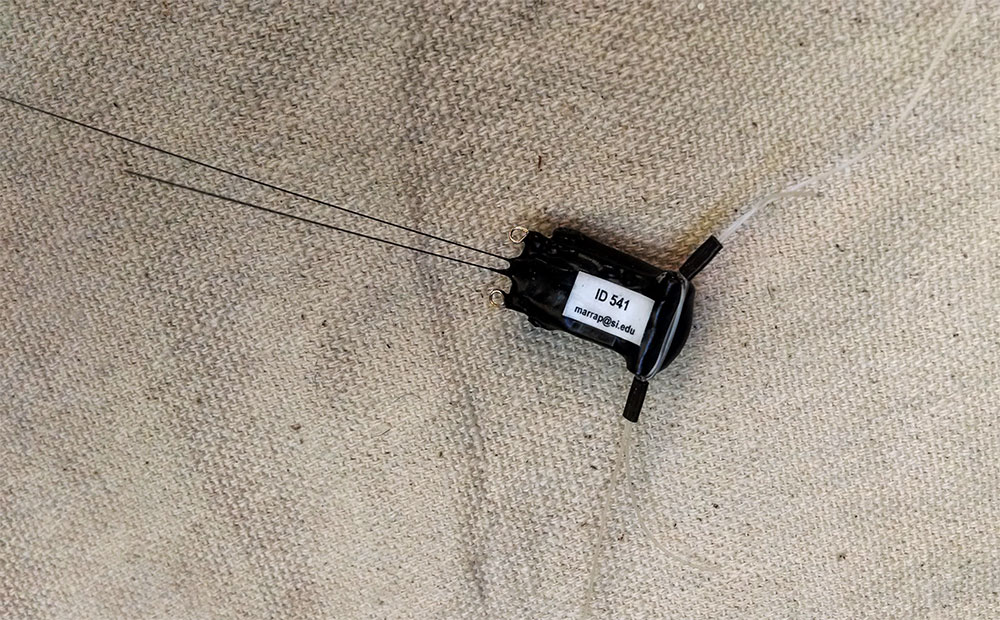

The new satellite transmitters, at 3.4 grams, are the lightest available and will allow us to determine the migratory connectivity of a whole new suite of species, including several shorebirds never tracked before throughout their annual cycle.

Shorebirds in North America have collectively declined by over 50% since 1968. Lots of theories exist but the truth of it is that we don't know why these declines are occurring, and this is in large part because we don't know where and why birds are dying.

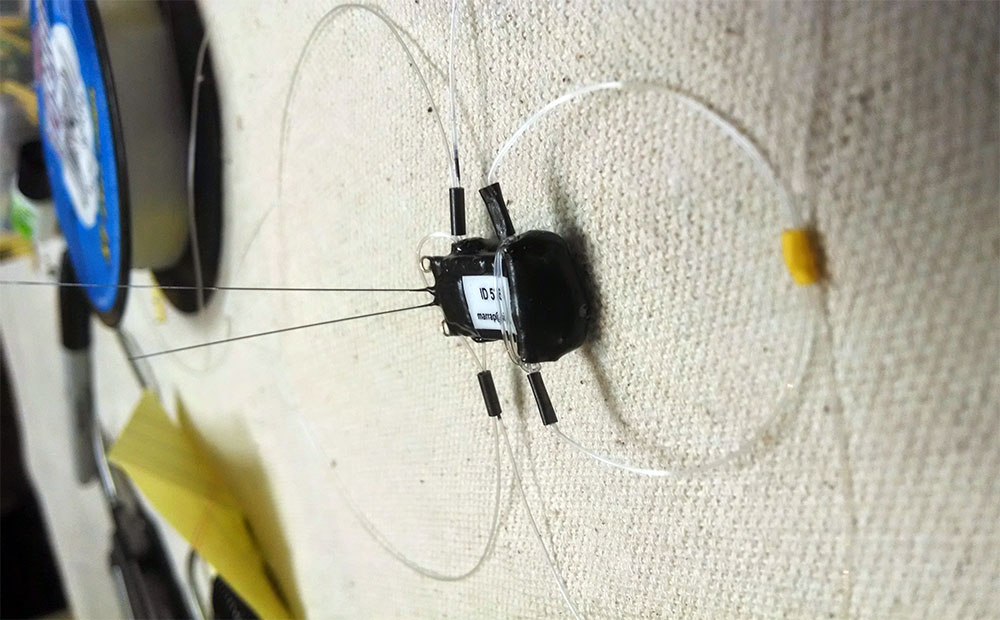

Take for example, the Black-bellied plovers that we trapped and tagged today. At 30 preset times the device wakes up, looks for a satellite constellation, stores a GPS fix with the geolocation in time of where the bird was—to a 10 meter accuracy—and then goes back to sleep.

The devices are programmed to wake up again at various times in the coming months to transmit those 30 points to an Argos satellite which then transmits it back to us. Transmitting big batches of data rather than each point when it's collected saves battery life, which means we can use smaller batteries that weigh much less. Although these devices probably won't allow us to locate individual birds when they die or even track birds in real time, these new transmitters will tell us new stories about smaller and smaller species.

Determining exactly where Black-bellied plovers from this part of Texas migrate in fall and spring, as well as where they breed, down to 10 meters, is a remarkable advance that will allow us to start studying how land-use, climate and other factors may have changed in these areas and is impacting birds and other wildlife.

Each day we move down the endless beach catching plover after plover in an attempt to uncover unknown migrations and other mysteries about the biology of these remarkable species.

- After pulling the birds out from under the net we attach a leg band and a flag, each with a unique number.

- We measure and weigh the bird and look to see if they're molting any feathers.

- We pull a small blood sample from their wings to determine if they're male or female or if these plovers are different from ones on the east or west coasts of the United States.

- We clip a feather to measure stable isotopes and contaminants, allowing for insights into what the birds have been eating, the latitude they molted their feathers at, or if they're carrying high pesticide or heavy metal loads.

- Finally, we place a harness around the leg on one side and then the other and position the small device and its antennae to the central part of their backs.

- We knot the harness and apply a small dab of glue so it doesn't come loose and then walk the bird to the shoreline cupped in our hands.

In almost ritualistic fashion, we kneel down facing the crashing waves of the Gulf of Mexico, place the dangling feet of the birds on the wet sand, and pull our hands apart toward the sky allowing these plovers to fly and leave here tomorrow or at least some point in the future for points north.

Natalie Riley of ConocoPhillips releasing a plover. © Tim Romano.

A Bill only a Mother Could Love

If there's one thing I've learned in all the years I have been doing wildlife biology, it's that things don't always work out the way you want them to. Today, we were to solidify that little lesson in the minds of our team not familiar with the age-old rule in field biology.

We're not in a laboratory or in a controlled situation. We're working in the field with wild animals and many unknowns. Things can and will go wrong, and the trick is to roll with it and adjust.

Our plan today was to catch and attach transmitters to Marbled Godwits and Long-billed Curlews, large shorebird species with bills that make you look twice, if not three times before you realize it's actually a bird.

David had been watching large numbers of both species in the city park in Corpus Christi for several weeks. Curlews and Godwits are short grass prairie specialists and although much of that native habitat had been destroyed, it turns out that grassy areas in city parks simulate prairie pretty well. David was cautiously confident that we had a good shot at catching good numbers of both species. Police had been notified that we might be using explosives within city limits.

Our group made up of our Smithsonian team (myself, Amy Scarpignato, Autumn-Lynn Harrison, Virginia Kromm), ConocoPhillips rep (Natalie Riley), professional photographer (Tim Romano) and video team (Randy and Tom from Bayou Productions) climbed into our Texas-sized caravan and headed into the big city. We were soon cruising by the "short grass prairie lawns" of the city park. No birds in sight. David was literally scratching his head.

Recent weather combined with the exceptionally high tides must have triggered these birds to move. After searching several areas we eventually came upon a flock of about 17 Marbled Godwits resting on the edge of a mudflat with some Black Skimmers just outside city limits. We were hopeful.

We placed a cannon net about 30 feet from the flock. The skimmers took off as soon as David approached with the net but the godwits stuck to their mud.

Black skimmers flying. Godwits are perched on the left and laughing gulls on the right. © Tim Romano.

Godwits, like many species of shorebirds like to save their energy and only fly if necessary. Once all was in place, David began "twinkling." You've heard of herding cattle, sheep and cats? Twinkling is essentially the same thing except it refers to the act of slowly moving a flock of shorebirds into the area where a net will harmlessly fall on the birds after launching from the cannon. David is an exceptional twinkler. Imagine half horse whisperer, half ballroom dancer.

David "twinkling" the godwits. © Tim Romano.

David moved into position behind the birds in almost knee high water and started moving his flock of large mesmerized shorebirds in the direction of the capture zone. I was watching from a distance day dreaming and confident that we would soon be holding these gorgeous things in our paws. Then, for no obvious reason, they flew. David bent over in frustration. Thirteen hearts of our team members hit the ground.

We regrouped and in five minutes they were back in the same spot. David twinkled them again. Five feet more and the net shot out of the cannon. The birds flew and this time they didn't come back.

Adjust and move on. We put out two Long-billed Curlew decoys and sure enough within ten minutes a Curlew and two Willets unsuspectingly landed near the plastic dummies. David began twinkling. The bird and David became one moving in almost perfect unison…or so we thought.

Long-billed curlew decoys. © Tim Romano.

David announced in his radio to get ready…3…2…1…hit it…BOOM! The net flew in a rapid explosion but fell short and the curlew flew. The plastic curlews were the only captures. We were done. Time to eat lunch and regroup.

Cannon net goes off but only the decoys are caught. © Tim Romano.

We decided to head to the beach for the rest of the afternoon where our adjustment was rewarded with the capture of a black-bellied plover and six red knots. We attached satellite transmitters on the plover—a first, and on three of the red knots.

As we released each of these remarkable birds on the Texas sand kissing the Gulf waters, I kept thinking how remarkable it is to still be able to watch each of these species fly in the wild. Given what's happening to shorebird populations, this is a vision that might not be something future generations will witness.

Pictures taken by Tim Romano.

Star Struck Ornithology

People go crazy with a glimpse of George Clooney or Julia Roberts. They stop in their tracks—pull out cameras, stare. Frankly—it's a little over the top. For me, a flock of Red Knots, a foraging Marbled Godwit, or even a single Piping Plover running to escape the waves turns me into the avian paparazzi. Such was the case in the afternoon of our first day on North Padre Island.

We arrived in Corpus Christi late morning after a 5:45 a.m. flight from Washington, D.C. After a bit of 3 stooges' shenanigans with the rental car company we were packed up in our blue minivan and on the road. We met up at local Mexican cantina with David Newstead, our local shorebird expert, along with his assistant, Owen, a volunteer named Barbara, and two students from Monterey, Mexico here to learn about birds—Isaac and David.

We spent lunch going over the details of the itinerary, organizing equipment and discussing safety. Safety you say? Today we were going to practice using explosives. Not a typical word used on a daily basis in the ornithological world, unless you work on shorebirds. Shorebirds require the use of cannon nets. As David put it—we don't want anyone to get decapitated. That makes good sense to me.

A front had moved through the day before with lots of rain and the 85-90 degree days on North Padre looked to be done for 2014. Today was windy and a bit brisk. The tide was very high. Our caravan of 3 vehicles, two pretty tough looking Texas style trucks and my blue, soccer dad-style minivan, inched along the beach searching for birds.

Padre Island beach. © Tim Romano.

We slowed occasionally to get glimpses of American Oystercatchers, Sanderlings, Royal, Caspian and Sandwich Terns or to avoid the surf casters hoping for a redfish. Not long after our tires hit the sand we were on to a group of 5 red knots. We stopped to discuss the plan and soak in glimpses of these rapidly disappearing species.

As I watched the 5 birds I couldn't help but think about the fact that they will spend the next several months in a fairly specialized world. Running back and forth along the beach, escaping the rolling surf, skittering through the Sargassum seaweed rack, all in an effort to probe their bills into the wet sand or seaweed for a crustacean meal.

It's all about two things for these birds now—getting food to maintain their energy stores and making sure they don't end up as the meal themselves. I had already seen two Peregrine Falcons cruise by and I'm sure there were several more as well as a handful of Merlins. The knots and the falcons have all just returned to Padre from points north for breeding—where we don't know. The knots were somewhere in the Arctic but the Arctic is a big place. We needed to catch these guys, attach these new transmitters and figure that out.

David and Owen packed the ends of two heavy projectiles with black powder and shoved them into two ends of a two-foot long container containing the cannon net. We placed the cannon net 15 feet from the surf, rolled about 50 feet of wire connected to an ignition switch back to a hiding point behind the dunes and waited for the birds to enter the net zone. Maybe 20 minutes after set up along with a little coaxing—BOOM we had them. More details on this process in the next few days. For now we had our birds and it was time to get them banded, attach a transmitter to one lucky knot, and hope for more success in the coming days.

Pictures taken by Tim Romano.

Trip Preparations

The Texas trip is hours away and although the field component begins tomorrow, our preparations for this expedition began months ago. In this second blog entry I want to give you all a little idea about what's involved in mounting a "simple" 6 day trip like this.

For this first ConocoPhillips sponsored expedition, we're focusing our efforts on four shorebird species of conservation concern that winter along the Texas Gulf coast region and breed somewhere in Alaska and the Canadian Arctic. Once these species leave Texas in spring we have no idea what migratory routes they take or where they breed—this is precisely what we want to find out. What happens in these places could decide their fate.

We chose to focus on the Long-billed Curlew, Black-bellied Plover, Marbled Godwit, and Red Knot. Just about all of North America's shorebird species are in sharp decline including the Red Knot—a species whose populations have plummeted by over 95% since 1968. Any information we gather, whether on their connectivity or on the techniques we use to study them could help save the species from extinction.

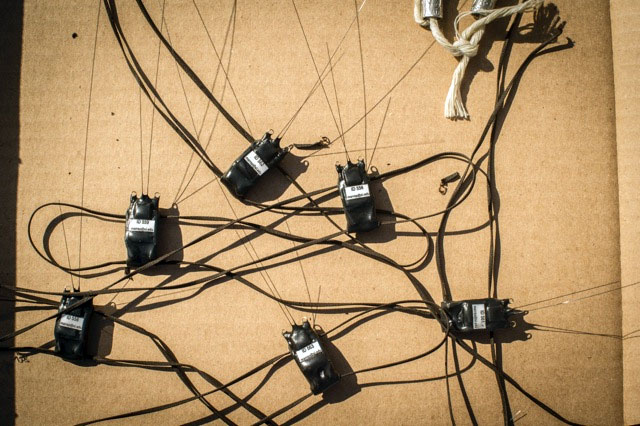

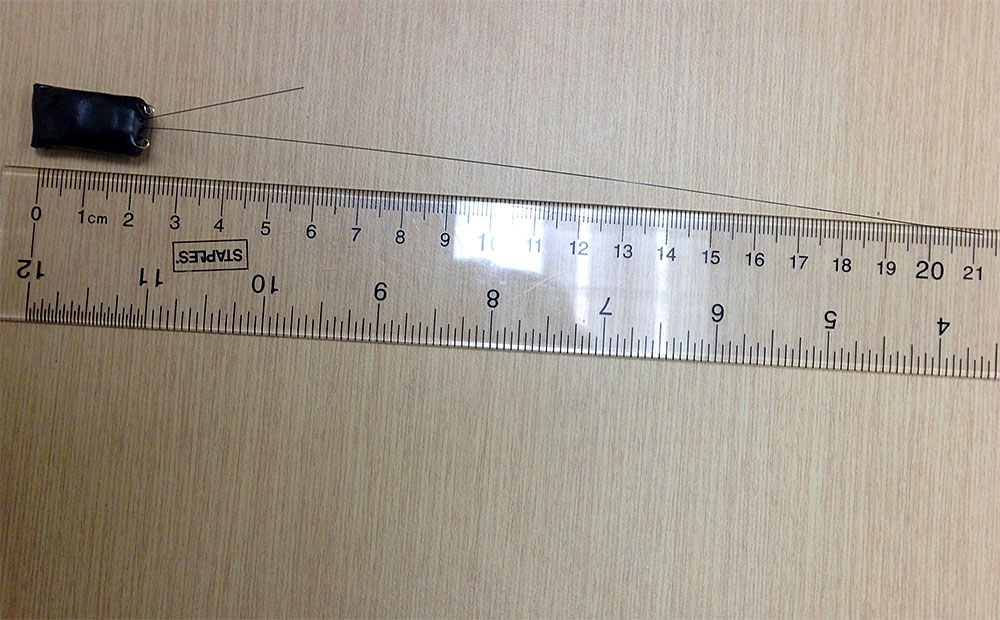

The first step was to begin discussions with local scientists in Texas and other shorebird experts throughout the country to gather more details on the how, where, what and when. We had to determine how to capture the species, what type and size transmitters the species could carry and what sort of harness and color markers to use. A typical guideline for the use of backpack transmitters is that they cannot be more than 3% of a bird's body weight.

To keep within this range, we chose a newly developed 3.4 gram satellite transmitters for the Knots, Plovers, and Godwits and 9.5 gram solar-satellite tag for the Curlews. In addition to transmitters, each bird will be banded with a USGS aluminum band engraved with a unique number and a color band.

Aluminum and colored bands.

The second step was getting approval and the permits from the various regulatory bodies. This process takes months not weeks. The banding of birds in the United States is controlled under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and requires a United States Federal Bird Banding and Marking Permit. This requires an application outlining proof of our experience and training and a research proposal that explains the purpose of our project.

Equally important is getting approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee from within the Smithsonian Institution. This committee ensures that all of our capture techniques and handling procedures are treating the animals with the utmost care. Then there's the Texas and local permits as well as permission from any of the property owners where we plan on catching the birds.

Almost there—next up getting the equipment together. The transmitters we put on the backs of the birds are made by hand and take 6 months to make so this order is submitted prior to knowing if permits have been approved. As you can see there's a bit of breath holding involved. Making matters more nerve racking was the fact that the 3.4 g transmitters (the lightest satellite devices ever deployed on an animal) had already been delayed by 9 months.

After months of back and forth and some field testing here in DC our stars, thankfully, aligned and the tags were in our hands just days ago. Finally, there's the purchasing of equipment…color bands from Poland, cannon nets, bleeding supplies and all sorts of specialized tools. Not mentioned was the organizing of the photographer and video team, booking hotel reservations, flights and cars. The only thing left to do is pack personal gear and kiss the families goodbye for a 5:45 a.m. Texas departure on Tuesday. North Padre Island here we come.

Shorebird Tracking in Texas

The Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, thanks to a grant from ConocoPhillips in support of the Migratory Connectivity Project, is advancing the conservation and understanding of birds throughout their full life cycle.

Migratory connectivity is the geographic linking of individuals and populations between one life cycle stage and another, such as between breeding and wintering locations for a migratory bird. Without understanding migratory connectivity, conservation investments can be ineffective because they are implemented at the wrong place or time, or for the wrong purpose.

The good news is that advanced technologies, such as satellite transmitters, light-level and GPS archival geolocators, stable isotopes and genomics are exponentially increasing our ability to track animals throughout their annual cycles and better understand their migratory connectivity.

Our first expedition for this project will be at the end of October to North Padre Island, Texas; a major stop-over and winter destination for many migratory shorebird species. We will deploy two types of the latest tracking technologies including 3.4 gram (less than the weight of 2 US dimes) satellite and 9.5 gram (about the weight of 2 US nickels) solar-charged satellite transmitters on 4 species of migratory shorebirds including Long-billed Curlews, Black-bellied Plovers, Marbled Godwits, and Red Knots.

With the information we collect, we can begin to tell the complete story of a year in the life of these species, including where they spend the winter, stop to refuel during migration, and most importantly, where they breed.

Stay tuned for pictures, videos, updates about our exciting expedition to the Texas coast, and of course regular updates on their movement tracks.