Giant Panda Mei Xiang Is Artificially Inseminated at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo

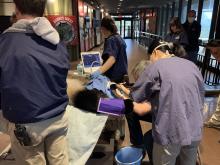

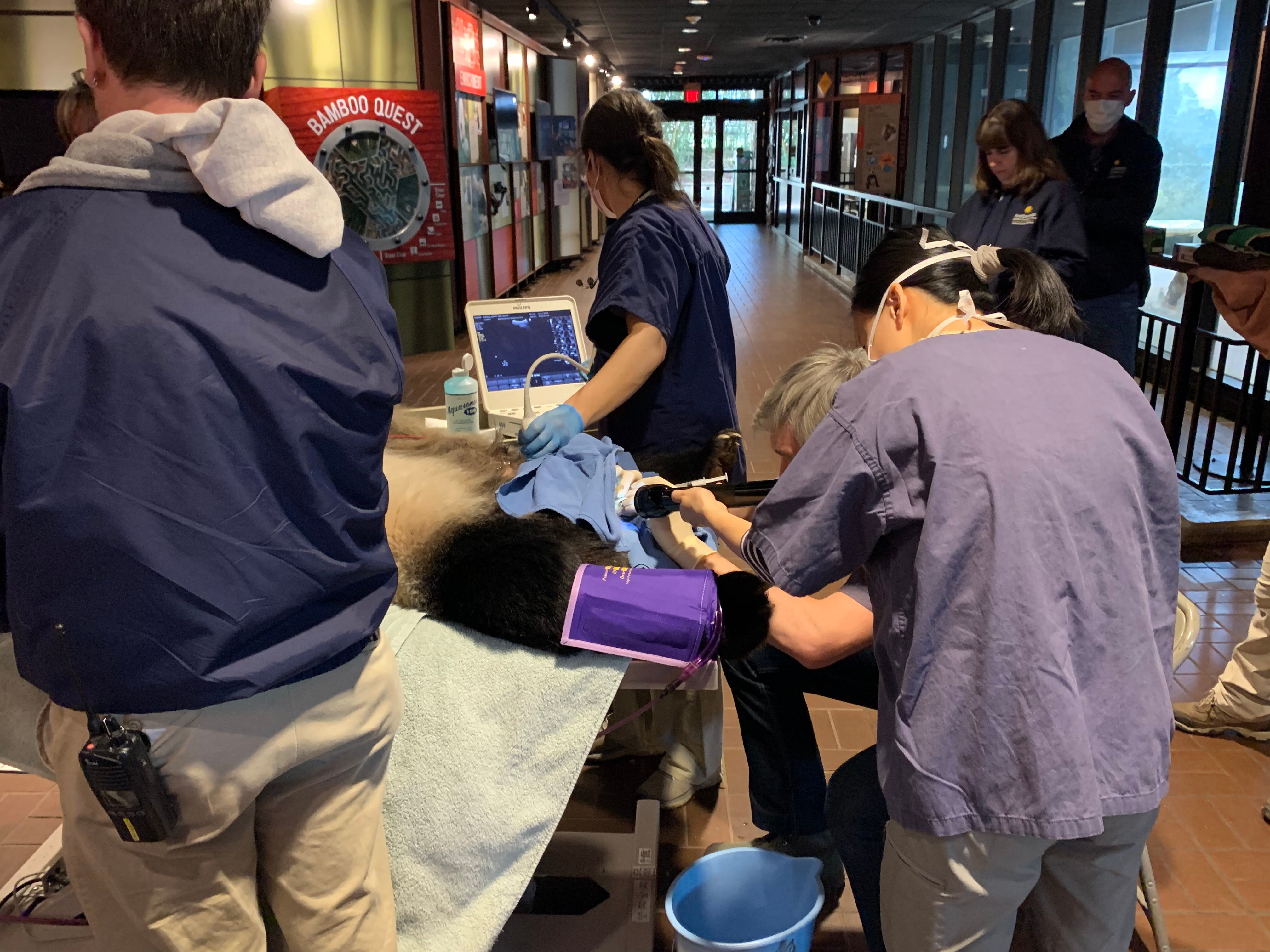

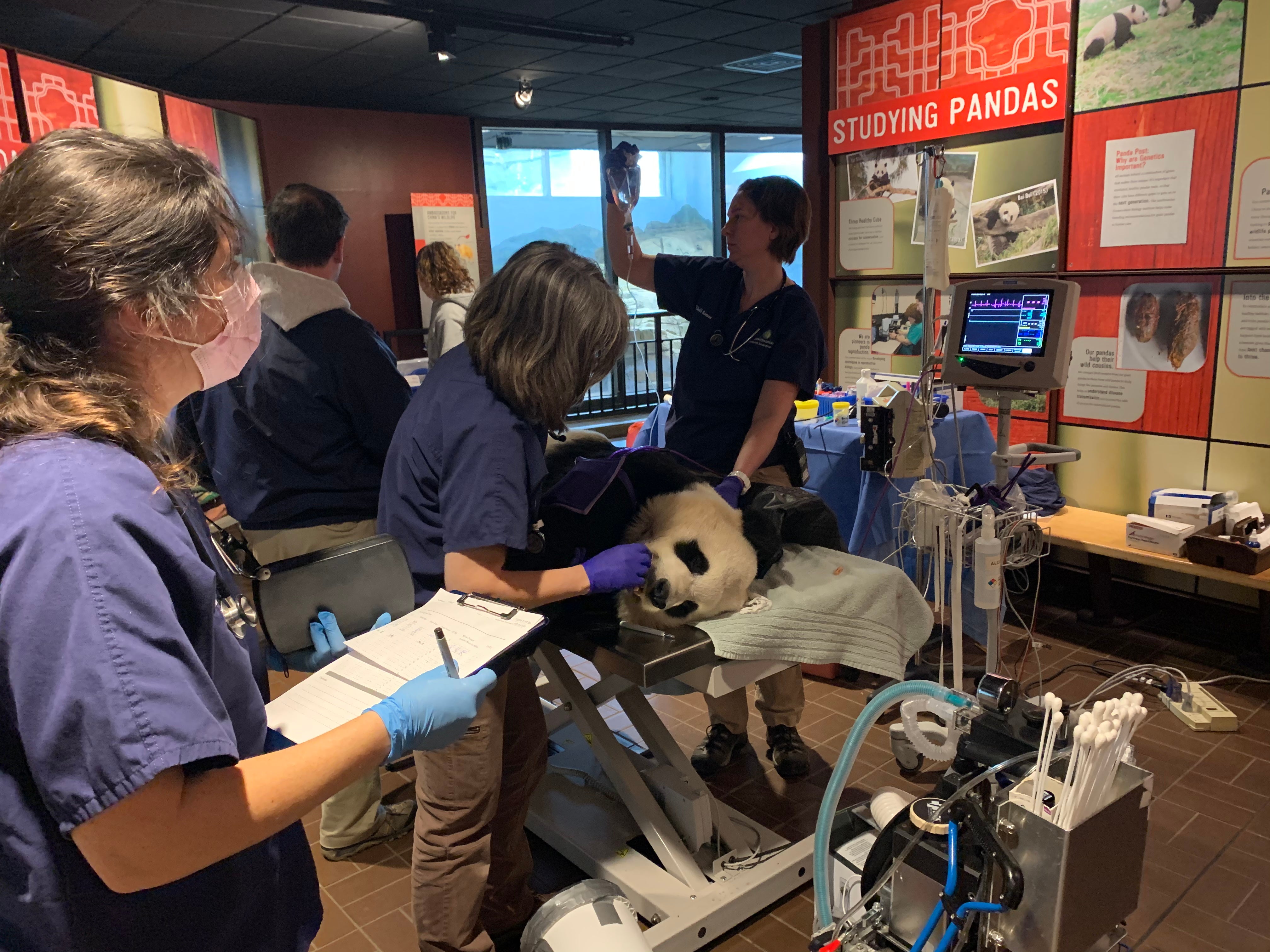

A team of reproductive scientists, veterinarians and panda keepers at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute performed an artificial insemination on giant panda Mei Xiang (may-SHONG) yesterday morning, March 22, at 9:45 a.m.

Scientists and keepers had been closely monitoring Mei Xiang’s behavior and hormones since she began displaying behavioral changes March 12, indicating she was entering her breeding season. Hormone analyses determined Mei Xiang’s urinary estrogen concentrations also began to increase on the 12th, meaning she was within a week or so of ovulating and able to become pregnant. Female giant pandas are only in estrus, or able to become pregnant, for 24 to 72 hours each year.

Since the window when a giant panda can conceive a cub is so short, the Zoo’s panda team performed an artificial insemination on Mei Xiang. They artificially inseminated her using frozen semen from Tian Tian (t-YEN t-YEN) for the procedure.

“This is another milestone in our long-standing and successful mission-critical 47-year giant panda conservation program and collaboration with Chinese colleagues to study, care for and help save the giant panda and its native habitat,” said Steven Monfort, John and Adrienne Mars director of the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. “Our team carefully planned this procedure with the safety of staff and Mei Xiang as the number one priority, taking extra precautions due to COVID-19.”

During the past week, Mei Xiang became increasingly restless, wandering her yard, scent-marking, vocalizing and playing in water—all behaviors that increase in intensity before she reaches peak estrus. Tian Tian immediately noticed the hormonal changes in Mei Xiang and began displaying behaviors toward her indicating he was ready to breed. He vocalized to her and constantly tried to keep her in his sight for the past week. During the past few days, he spent much of his time at the “howdy window” that separates their yards. Mei Xiang did not respond positively to any of Tian Tian’s vocalizations until yesterday.

As Mei Xiang exhibited estrus behaviors, the Zoo received approval for its breeding plans from the China Wildlife Conservation Association and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which monitors giant panda research programs in the United States. Mei Xiang is 21 and near the end of her reproductive life cycle, but there are pandas who have had cubs when they were older than she is now. Based on data from scientists in China and other zoos with pandas, females can breed into their early 20s.

As a public health precaution due to COVID-19, the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute is temporarily closed to the public. Special precautions implemented to minimize person to person contact ahead of Mei Xiang’s artificial insemination included delivering medical supplies and setting up equipment in advance, as well as, limiting the number of staff present during the insemination event. Per usual procedures, the Zoo’s expert team of panda keepers closely watched Mei Xiang’s behavior, which is the best indicator, in addition to hormone analysis, that she has reached peak ovulation. These behaviors include an increase in positive vocalizations like bleats and chirps and walking backward with her tail up. Historically this behavior has tracked with peak estrogen and progesterone rise. Due to the successful banking of semen from Tian Tian over the past several years as part of the Smithsonian’s cryopreservation initiative, the team used frozen semen instead of fresh to reduce overall staff contact time and work load in consideration of the needs of staff and the other animals in the collection.

The Zoo’s webcams, including the giant panda webcam, remain online, but volunteers are not operating them, so animals may not be visible at all times.

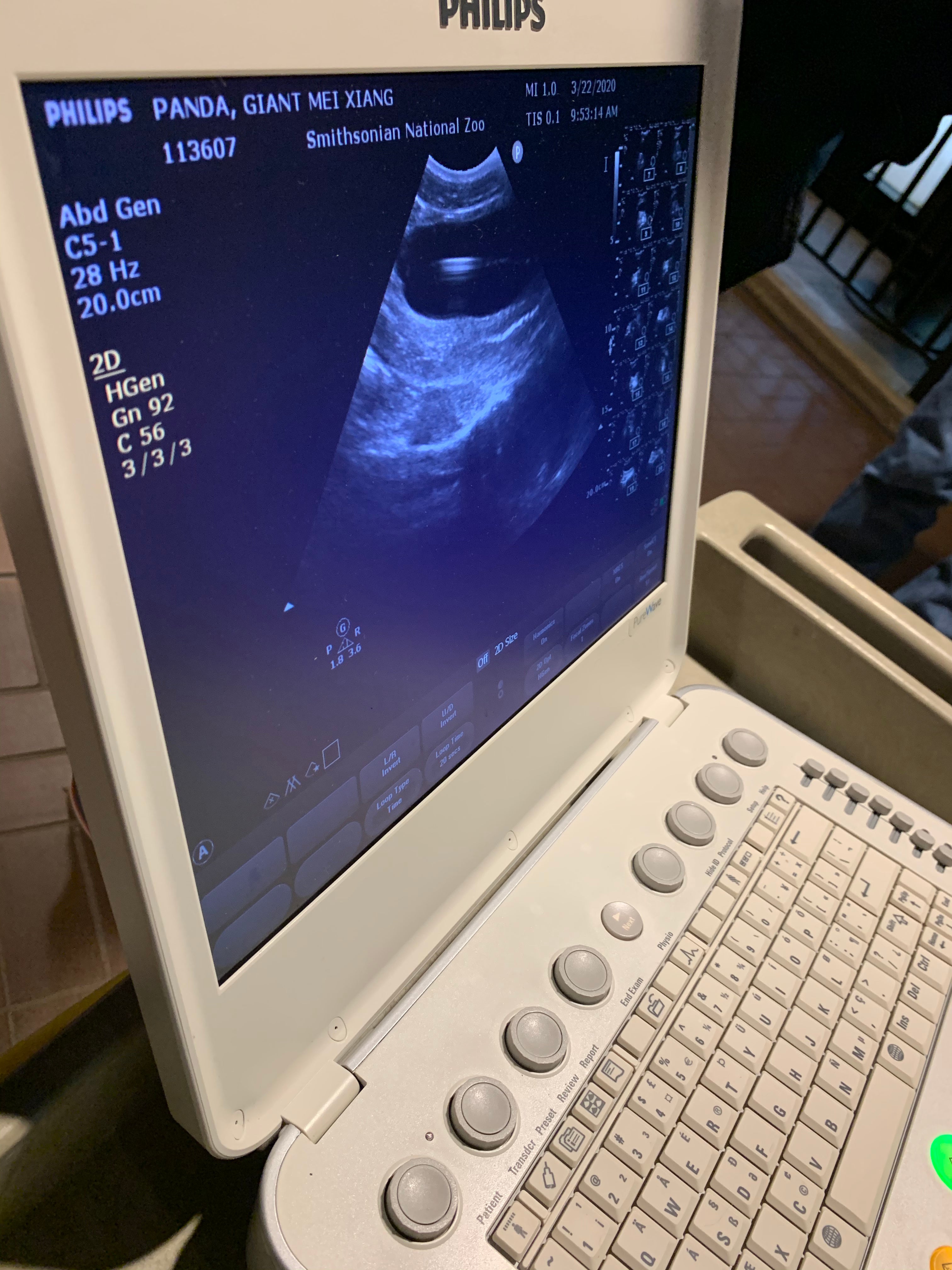

The panda team will not know if the artificial insemination was successful for several months. Giant panda pregnancies and pseudopregnancies generally last between three to six months. Veterinarians will conduct ultrasounds to track changes in Mei Xiang’s reproductive tract and determine if she is pregnant during the next several months. Scientists will also monitor her hormones to determine when she is near the end of a pseudopregnancy or pregnancy. There is no way to determine if a female is pregnant by hormone analysis and behavior alone. Mei Xiang’s hormones and behavior will mimic a pregnancy even if she is experiencing a pseudopregnancy. The only definitive way to determine if she is pregnant before giving birth is to see a developing fetus on an ultrasound.

Giant pandas are listed as “vulnerable” in the wild by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. There are an estimated 1,800 in the wild. The Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute is a leader in giant panda conservation. Ever since these charismatic bears arrived at the Zoo in 1972, animal care staff and scientists have studied giant panda biology, behavior, breeding, reproduction and disease. These experts are also leading ecology studies in giant pandas’ native habitat. The Zoo’s giant panda team works closely with colleagues in China to advance conservation efforts around the world. Chinese scientists are working to reintroduce giant pandas to the wild.

The Zoo’s giant Panda reproduction research collaboration contract with the China Wildlife Conservation Association expires Dec. 7. The Zoo is in the process of renewing this agreement.

The Zoo will continue to provide updates on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter using #PandaStory and through the Giant Panda e-newsletter.

Related Species:

Image Gallery