New Virus Discovered in Myanmar by Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute's Global Health Program

Another Virus Is Detected in Myanmar for the First Time

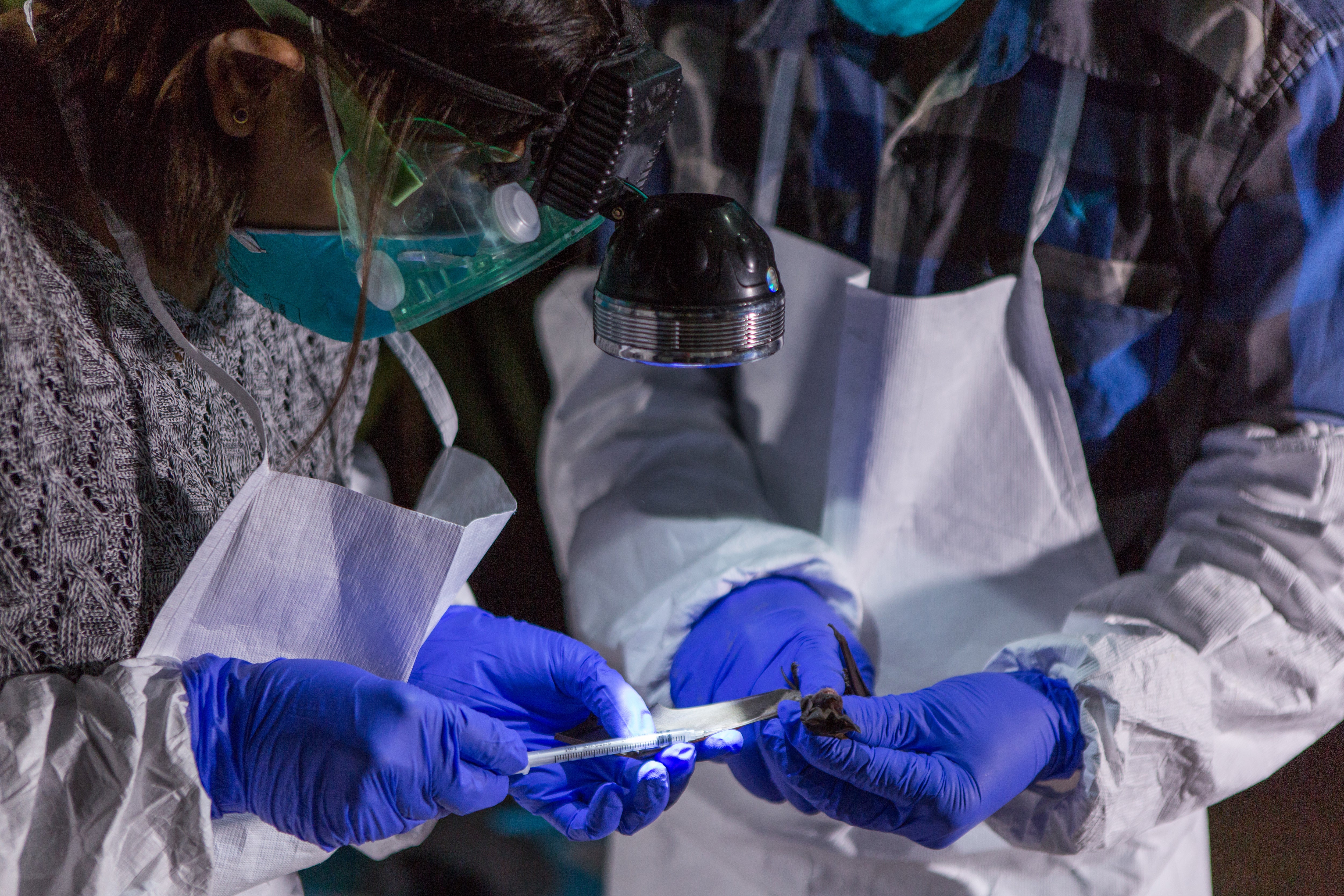

Smithsonian and University of California, Davis scientists and partners have discovered a new coronavirus in a species of bat in Myanmar as part of routine surveillance for the PREDICT project, funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). A second virus was also detected in Myanmar for the first time; it had been previously detected in bats in Thailand. There is no evidence that these viruses pose a threat to human health, and because these are newly detected viruses, researchers will continue to study them to gain a better understanding of their risk. This is the first detection of viruses in wildlife for the PREDICT/Myanmar team and marks a milestone in the success of the project.

“At the time of this finding, we have finalized testing from samples of 150 animals of which we had two positives,” said Marc Valitutto, a wildlife veterinarian with the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute's Global Health Program. “This is the first step to understanding what kind of viruses are present in Myanmar’s wildlife populations and lays groundwork for additional work to understand their potential risk to humans and other animals. We still have hundreds more samples to test, and we expect that we will find more novel viruses.”

The two viruses belong to the coronavirus family, which also includes two pathogens that have had devastating effects on human health—Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). Although in the same viral family, the two new coronaviruses are not closely related to SARS or MERS. One virus has never been detected anywhere in the world before. The other virus has been previously detected in bats, but only in Thailand. Scientists detected the viruses in saliva and fecal samples that the team collected from insectivorous bats in the Chaerephon genus.

The samples were tested at University of California, Davis’s One Health Institute Laboratory.

PREDICT is a global disease-surveillance project working in 30 countries to strengthen capacity for detection and discovery of viruses that can move between animals and people and have pandemic potential. The PREDICT team in Myanmar will continue collecting and analyzing samples from bats, rodents and primates in the field, to look for known and new viruses. The researchers also plan to analyze samples from humans from the same study area that interact with wildlife, to better understand how viruses are shared between populations and to identify potential risk factors for viral transmission.

“We are seeing once pristine forests under threat for increased development, which brings wildlife in these areas in close contact with humans,” Valitutto said. “If we can help strategically protect these forests and guide human activity appropriately, then the animals will remain protected, and the people safe from potential spillover of disease. Protecting the forests is a win-win strategy for both humans and wildlife.”

The PREDICT/Myanmar team is testing all of the samples for five viral families from which researchers have previously detected zoonotic diseases including corona-, filo- (such as Ebola), flavi- (such as Zika), influenza and paramyxo-viruses. The researchers will then examine these results, including contact with humans to try to understand the potential risk for spillover. The team will share this information with the government of Myanmar to help inform on policies and strategies that may mitigate the risk of viral transmission from wildlife to humans.

The PREDICT project is part of USAID’s Emerging Pandemic Threats program, which focuses on building capacity to identify viruses in high-risk areas for spillover from animals to humans, at high-risk interfaces where diseases are most likely to emerge. PREDICT is a consortium led by the University of California, Davis, with the Smithsonian Institution, EcoHealth Alliance, Metabiota, Wildlife Conservation Society and partners in each host country. The Global Health Program is part of PREDICT teams in Myanmar and Kenya.

About the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute

The Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute's Global Health Program (GPH) leverages multidisciplinary expertise in wildlife medicine, conservation pathology, training of international professionals and investigation of emerging infectious disease to combat threats to conservation and public health worldwide. GHP is a part of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI), which plays a leading role in the Smithsonian’s global efforts to save wildlife species from extinction and train future generations of conservationists. SCBI spearheads research programs at its headquarters in Front Royal, Virginia, the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington, D.C., and at field research stations and training sites worldwide. SCBI scientists tackle some of today’s most complex conservation challenges by applying and sharing what they learn about animal behavior and reproduction, ecology, genetics, migration and conservation sustainability.

About PREDICT

PREDICT is enabling global surveillance for viruses that may spillover from animal hosts to people by building capacities to detect and discover viruses of pandemic potential. The project is part of USAID’s Emerging Pandemic Threats program and is led by the UC Davis One Health Institute. The core partners are USAID, EcoHealth Alliance, Metabiota, Wildlife Conservation Society and Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. Scientists work in 28 countries in Africa and Asia testing for five viral families—coronaviruses (e.g., SARS/MERS), filoviruses (e.g. Ebola), paramyxoviruses (e.g., Nipah/Hendra), influenza viruses (e.g., H1N1, H5N1, H7N9) and flaviviruses (e.g., Zika)—in wildlife, livestock and humans, to understand the risk of spillover. As part of this effort, lab scientists around the world are trained to perform viral testing—a vital skill in case an outbreak should emerge. Field researchers are trained to safely handle and sample animals by capture and release. Data from the project (when approved by host country governments) is shared with animal and human health sectors to inform decision making and is made available to the public and global health community at www.data.predict.global.

Image Gallery