Smithsonian and Partners Map Extensive Transnational and High-Seas Travels of Migratory Marine Animals

Study Results Set To Bolster Success of International Conservation Agreements in Protecting Imperiled Species

Nearly 50 percent of the planet is covered by the high seas, referred to as the “Wild West” of the ocean and among the least protected areas in the world. In September, the United Nations will convene to discuss the management of the high seas beyond national jurisdiction and opportunities for countries to collaborate on the successful protection of species that travel through these remote waters.

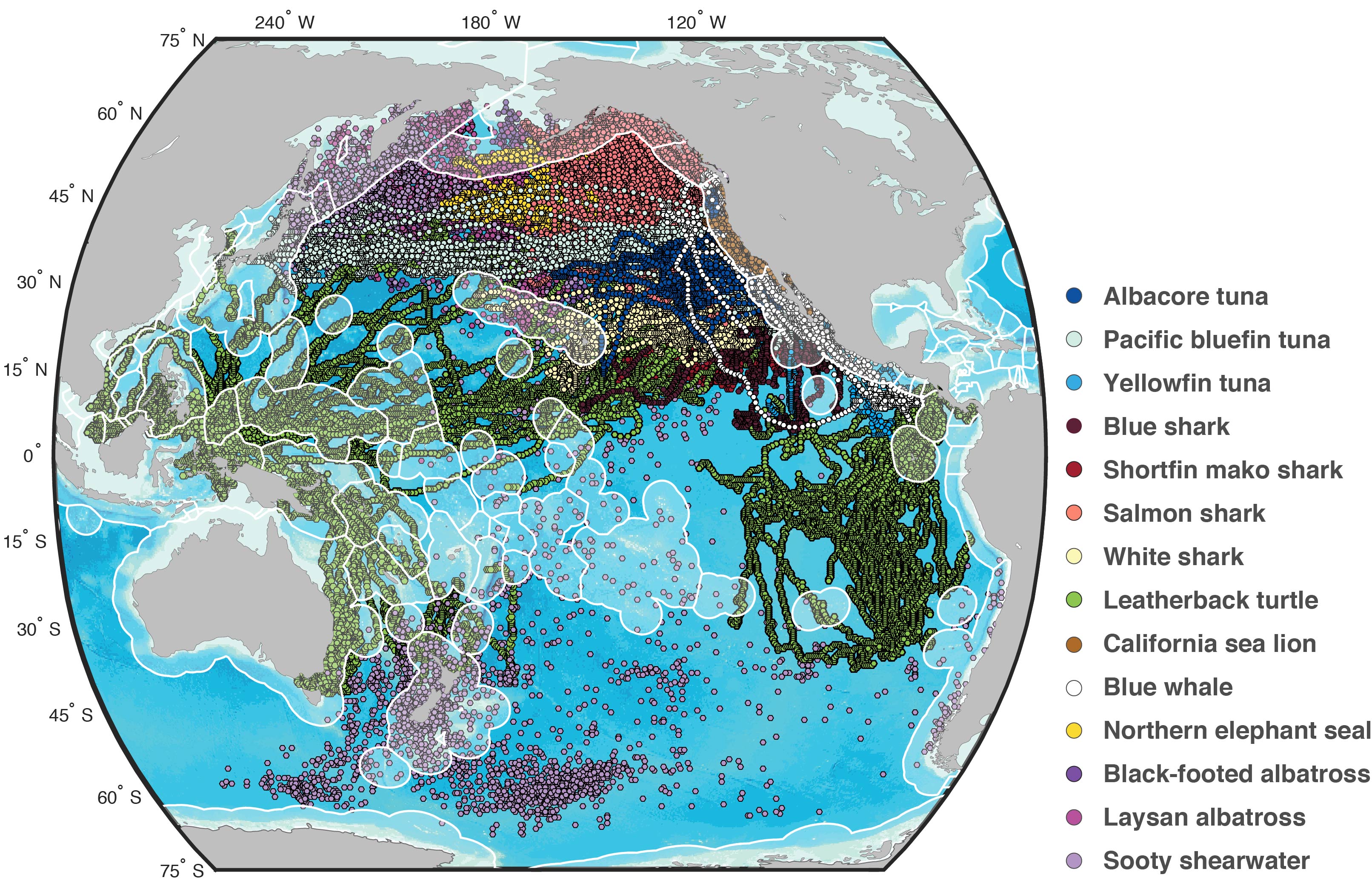

A new study from the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, the University of California at Santa Cruz, Stanford University and partners will be central to these discussions. The study, published today, Sept. 3 in Nature Ecology & Evolution, reveals not only which countries’ waters 14 migratory marine predators regularly travel through in the Pacific Ocean, but also the importance of the high seas to migratory species. The paper’s lead author, Autumn-Lynn Harrison, a research ecologist at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, will present the study’s key findings during the United Nations General Assembly’s Intergovernmental Conference.

“For the first time, we have real numbers to indicate, at an ocean-basin scale and for multiple migratory species, the annual movements through the high seas and the amount of time they spend there,” Harrison said. “The patterns and maps that we can provide to the United Nations as they develop this treaty will show that these animals are truly our shared responsibility. My vision is for countries to work together effectively to conserve these species.”

The study uses one of the most extensive data sets available for marine species tracked with electronic tags as part of the Census of Marine Life’s Tagging of Pacific Predators (TOPP) project. This includes tracking data for leatherback turtles, Pacific bluefin tunas, white sharks, sooty shearwaters, California sea lions, as well as others. Cumulatively, the animals in the study visited the jurisdiction of 37 countries and some, including the Laysan albatross, a threatened species, spent 75 percent of their annual cycles in the high seas. All of the 14 species—even those that tend to stay close to the coast, such as the California sea lion—spent some period of time during their migration in the high seas, where they face mounting threats, including plastic pollution and overfishing, illegal fishing and incidental catch of non-target species (bycatch).

One of the species that travels through the jurisdictions of the highest number of countries—the leatherback turtle—is also the most critically endangered of those included in the study. The turtle populations that the researchers tracked could face a 96 percent decline by 2040, and leatherbacks are a priority species for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), contributors to the paper. Because they travel through more than 30 countries and the high seas, leatherback turtles highlight the need for multi-lateral, cooperative and international agreements to manage the species, according to the paper’s authors.

Not all species traveled through dozens of countries like the leatherback turtle. Some traveled only through a couple of countries, making their management more straightforward. For those species, such as the California sea lion, this study shows which countries need to collaborate on management decisions and when during the year those measures need to be put into place.

“Migratory marine animals spent most of their lives beneath the sea or high up in the air, so it is hard to determine which countries they are in at certain times of the year and which countries are essential to their conservation,” Harrison said. “Determining which stamps each of these species would have in their passports helps us understand which countries need to cooperate to ensure the animals are protected during the most important parts of their journey.”

The researchers will use the results of the study in building new management plans, and in the coming months will be continuing to share the information with international collaborators and the United Nations. A team of researchers, including Harrison, will next be broadening this work beyond the Pacific Ocean to provide the same kind of information for migratory species across other oceans.

“SCBI is an expert in animal-movement studies, so using animal-tracking data to inform conservation action is a natural fit,” Harrison said. “Management of these species can be complex, but we have the advantage of working with some charismatic, culturally, commercially and ecologically important species. There’s a groundswell of interest in migratory species and in protecting the oceans, so I am hopeful this work can make a difference.”

In addition to Harrison, the co-authors of the paper are founders of the TOPP project: Daniel Costa at the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC); Barbara Block at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station; Steven Bograd at NOAA Fisheries; Arliss Winship at NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science; Scott Benson, Heidi Dewar, Peter Dutton and Suzanne Kohin at NOAA Fisheries; Michelle Antolos and Patrick Robinson at UCSC; Aaron Carlisle at University of Delaware; George Shillinger at Upwell; Sal Jorgensen at the Monterey Bay Aquarium; Bruce Mate at Oregon State University; Kurt Schaefer at the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission; Scott Shaffer at San Jose State University; Samantha Simmons at the Marine Mammal Commission; Kevin Weng at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science; and Kristina Gjerde at the IUCN Global Marine and Polar Program.

Image Gallery