Smithsonian Scientists Dry and Store Live Ovarian Tissues Above Freezing Temperatures for the First Time

It Is the First Step in Preserving Tissues Long-term Without Freezing

Scientists at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) have preserved complex ovarian tissues in domestic cats above freezing temperatures by dehydrating them with the help of microwaves. Over the past five years, scientists have been able to successfully dehydrate single cells, such as sperm cells or germinal vesicles (oocytes’ nuclei), but this is the first time it has been done in ovarian tissues, which contain thousands of different cells with various functions, including eggs at the early developmental stage. The findings were published today, Dec. 4, in PLOS ONE and could provide better options for fertility preservation of human cancer patients or endangered wildlife.

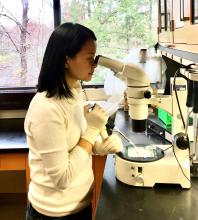

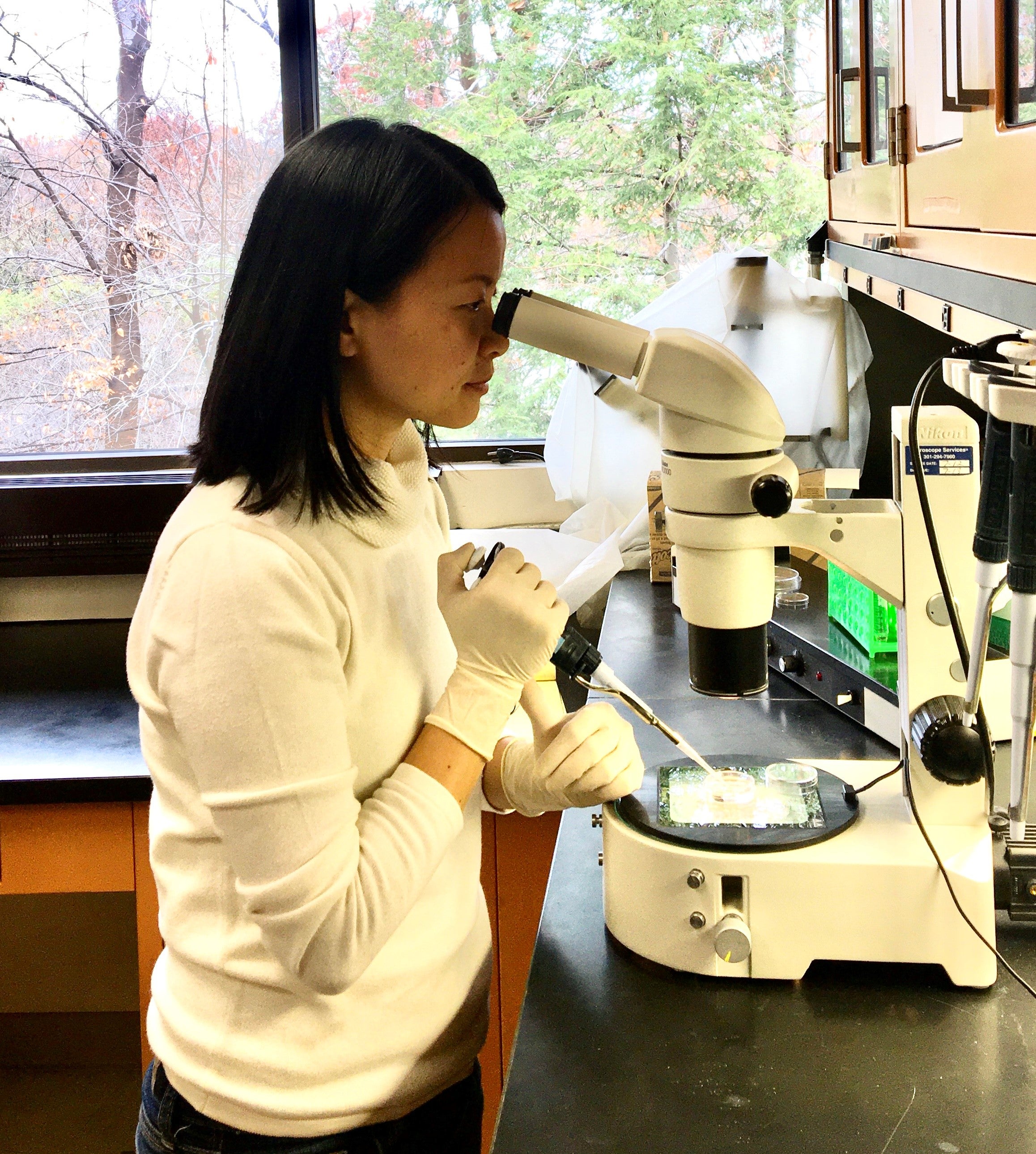

“It took several years of research, but we are very excited by these encouraging results,” said Pei-Chih Lee, reproductive biologist at SCBI and lead author of the paper. “Of course there is room for improvement, nonetheless this is the first step toward a more economical way of preserving live tissues without the need of liquid nitrogen.”

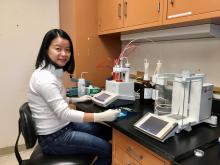

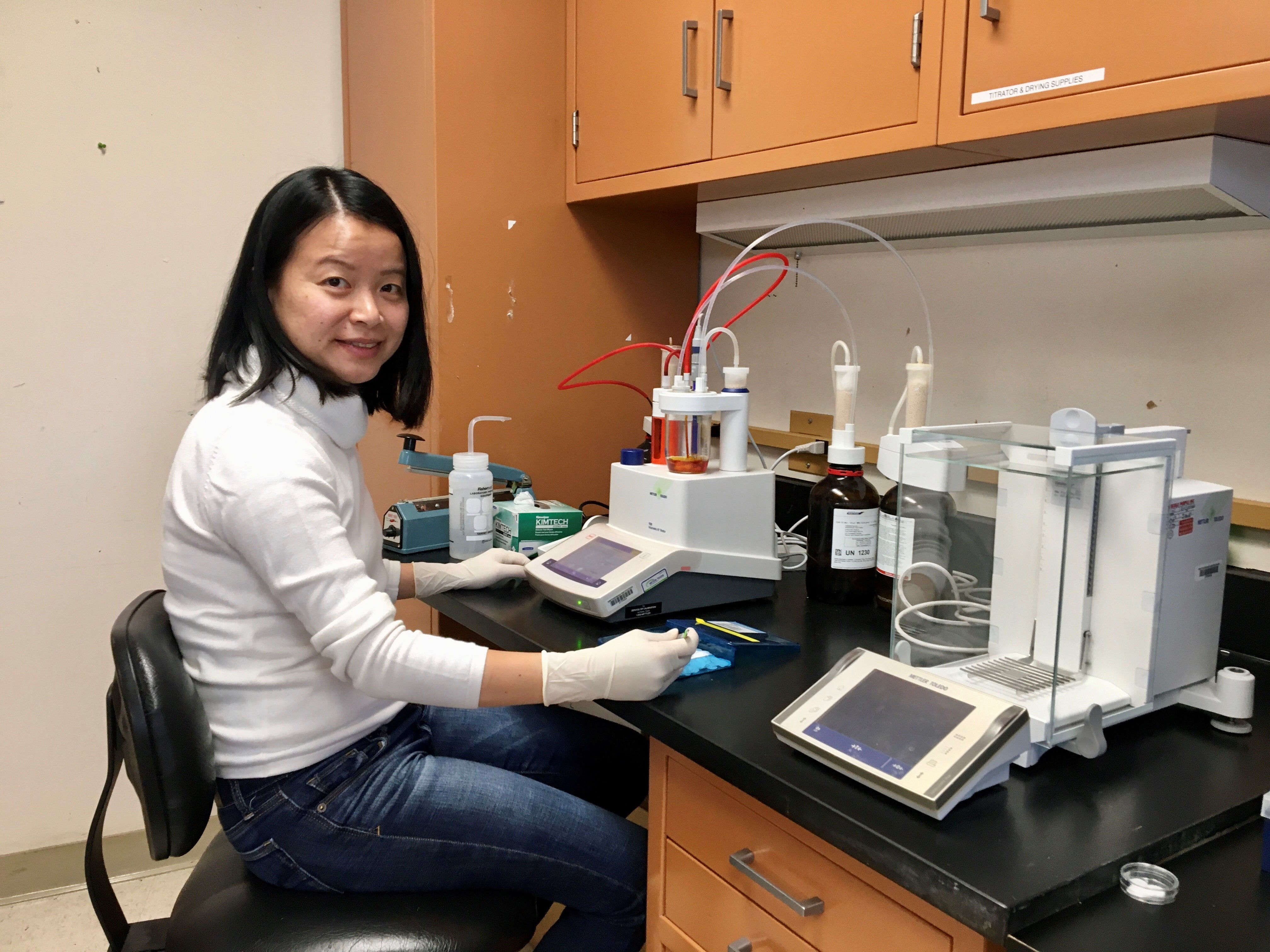

Researchers adapted the concept from invertebrate species that survive dry conditions or drought by producing trehalose in their cells. Trehalose is a natural sugar that forms a stable and protective glass within and around the cells when water content gets very low. Mammalian tissues do not have the same capacity, therefore researchers ‘infused’ the tissues with a solution of trehalose. Once they made sure that trehalose had permeated the cells, scientists then progressively removed water from the tissue samples by microwaving without damaging them. The tissues could then be stored above freezing temperatures at 4 degrees Celsius. Scientists were able to rehydrate the samples by simply adding water back to them. Tissues maintained their structures, DNA integrity and basic functions (including the transcription of the DNA). Ongoing studies are focusing on the tissue resilience and refinement of the technique.

Scientists have been preserving gonadal tissues, sperm, eggs and embryos for decades by freezing them in liquid nitrogen tanks or specialized freezers, then thawing the samples when they want to use them. However, liquid nitrogen is expensive and needs to be replenished regularly. If samples were dried and stored at room temperatures, many more scientists around the world could easily preserve reproductive tissues of endangered animal species. Those tissues could be used to produce gametes and create embryos, which would enhance the maintenance of genetic diversity in very small populations. The more genetic diversity is retained in a species the healthier and more resistant to diseases it is and less likely it is to go extinct.

The findings also could also one day help human cancer patients. Female cancer patients could store their own dehydrated ovarian tissues while they are receiving treatment (much more convenient and less expensive than frozen storage) and subsequently use those tissues for procedures like in vitro fertilization after cancer treatment.

“This is a breakthrough,” said Pierre Comizzoli, reproductive biologist at SCBI and senior author of the paper. “This proves that dehydrating living tissues for long-term storage at ambient temperatures is possible; it is not science fiction.”

The Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute plays a leading role in the Smithsonian’s global efforts to save wildlife species from extinction and train future generations of conservationists. SCBI spearheads research programs at its headquarters in Front Royal, Virginia, the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington, D.C., and at field research stations and training sites worldwide. SCBI scientists tackle some of today’s most complex conservation challenges by applying and sharing what they learn about animal behavior and reproduction, ecology, genetics, migration and conservation sustainability.

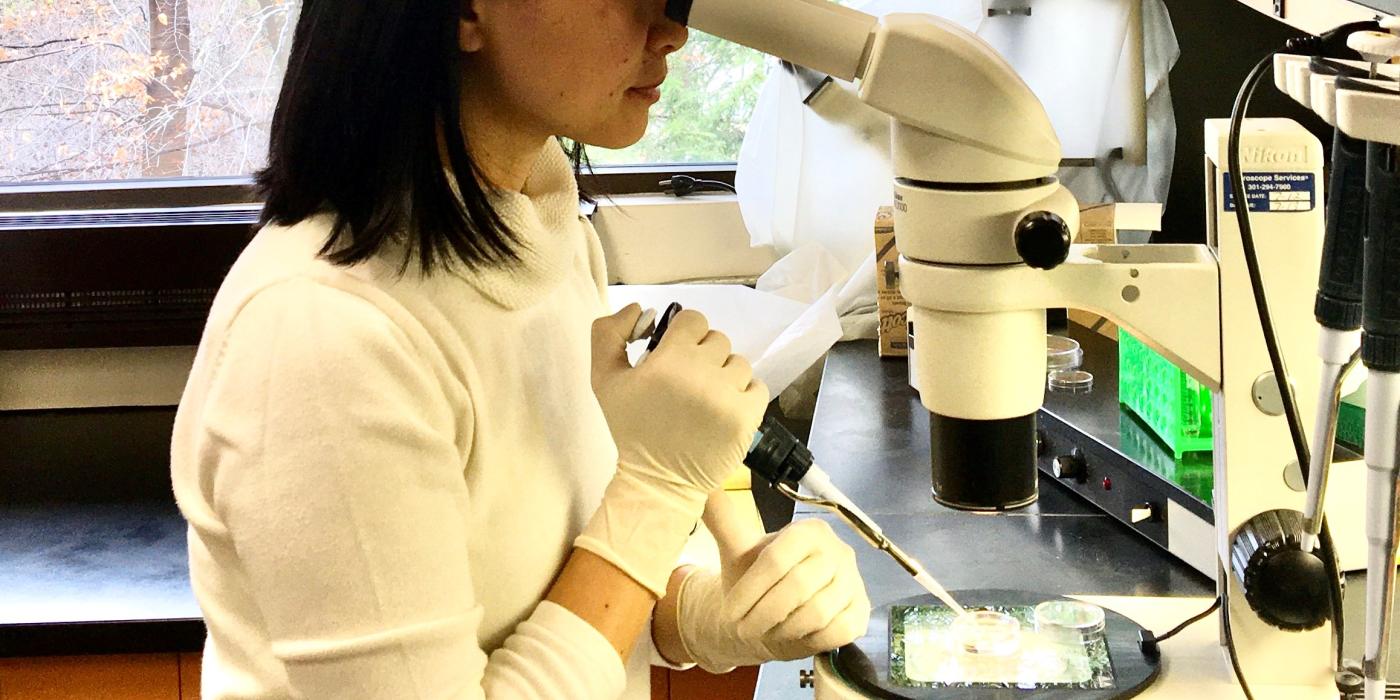

Image Gallery