From Bleats to Bonds: Early Signs of Affection Between D.C.’s Giant Pandas

Over the past seven months, our team has been getting to know giant pandas Bao Li and Qing Bao as they settle into their new home here at the David M. Rubenstein Family Giant Panda Habitat. Whenever new animals arrive, we spend a lot of time observing their behaviors. We get to know their personality quirks, their likes and dislikes, and we take note of the activities and enrichment items they seem to enjoy most. This teaches us a lot about their individual needs and preferences.

In the wild, giant pandas live mostly solitary lives. They only come together during breeding season. We replicate this with the Zoo’s pandas, too. Typically, giant pandas begin breeding between the ages of five and seven. At 3.5 years old, Bao Li and Qing Bao are still considered juveniles—a bit too young to breed. Although our pandas don’t share an enclosure, they do live right next to each other. Through their “howdy” windows—two mesh screens along the fence line—the pandas can see, smell and vocalize at one another on their own terms.

Giant panda Qing Bao climbs over a log in her outdoor habitat. Credit: Roshan Patel/Smithsonian

During the fall and winter seasons, Qing Bao didn’t spend much time near the howdy windows. More often than not, she carried some bamboo or a toy up a tree, ate and napped for a few hours. Occasionally, Bao Li noticed Qing Bao and called to her, but she did not look for him or call back. She paid little attention to the panda next door.

Watch giant panda Qing Bao somersault, pounce and play with toys in her indoor habitat.

Around mid-March, Qing Bao’s behavior began to change. Some days, she followed her normal routine. Others, she seemed more restless, energetic and aloof. She wandered around her habitat and scent marked various places. She rolled and tumbled with her toys and tree branches. To cool down, she splashed around in her pools. Sometimes, she sought out attention from keepers and played in the hose spray while we cleaned.

Bao Li is on the move! Watch him splash and climb in his indoor habitat.

On the other side of the fence, we saw similar behaviors from Bao Li. He patrolled the habitat, climbed trees (and broke branches), played in water, investigated scents in his environment and left lots of scent marks.

Giant pandas communicate a lot just through scent marking. They make scent marks using a gland under their tails that secretes an oily substance. The smell is very interesting to giant pandas and contains information about the panda who left it, such as their sex, age, fertility and more. In the wild, pandas come across other pandas’ scents more than they come across other pandas! At the Zoo, we often see Bao Li and Qing Bao exploring the areas where the other has left a scent mark.

Many of the behaviors we saw with Bao Li were very similar to when his grandfather, Tian Tian, was in rut—the period when a male giant panda readies himself for breeding. And, many of Qing Bao’s behaviors mirrored those of Bao Li’s grandmother, Mei Xiang, as she was entering estrus. Just as we began to wonder whether our bears were entering “panda puberty,” something exciting happened.

Howdy, panda! Giant pandas Qing Bao (foreground) and Bao Li interact with one another at one of the "howdy" windows separating their habitats. The bears' behaviors indicate that they are very interested in one another—a great sign for breeding in the future.

In late-April, Qing Bao approached the howdy window. She bleated and chirped at Bao Li—a sign that she was very interested in him. A bleat sounds like a sheep’s “baa,” but with a higher pitch and longer trill. Bao Li—who has always been the “talker” of the two—eagerly bleated back.

From that moment, the bears’ behaviors ramped up tremendously. Whenever they were outside, they stayed near the howdy windows. Although Bao Li and Qing Bao could not touch one another through the mesh, they tried to get as close to one another as they could. They rolled around, put their paws up and vocalized back and forth—intensely. Qing Bao even pressed her back up against the mesh and allowed Bao Li to sniff her.

We placed bamboo and shoots next to the windows so they could watch each other while they ate. If one of them walked away, the other ran over and called for them. It was adorable—and a sure sign that our bears’ hormones were changing!

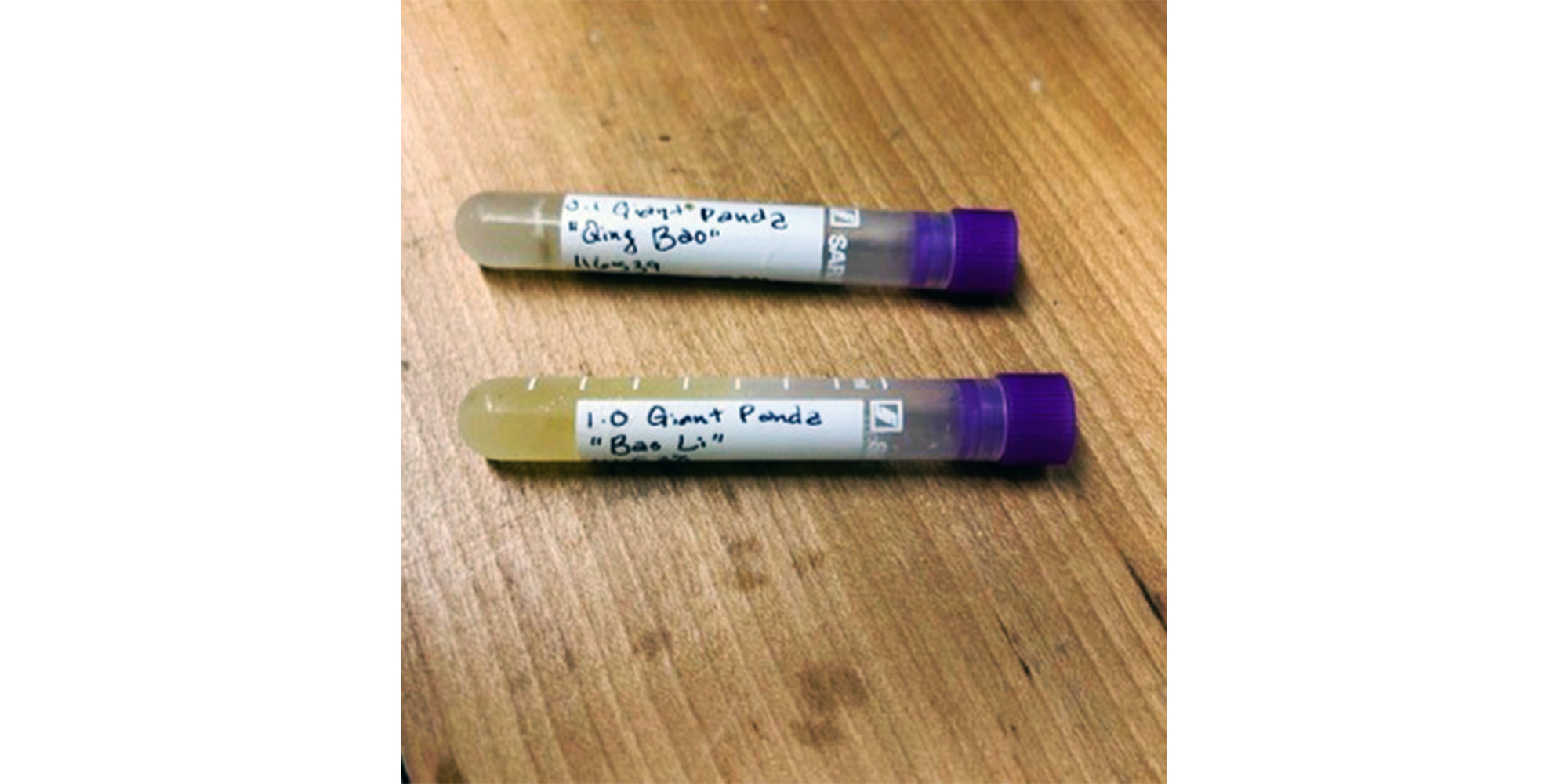

Ever since the pandas’ arrival last October, we’ve been collecting urine samples from both bears. The Zoo’s endocrinologists study Bao Li and Qing Bao’s hormones by analyzing their urine samples and tracking changes over time.

Bao Li and Qing Bao are very good about leaving us samples before they head outside in the morning. Using a syringe, we collect the fresh urine from the floor. Then, we split the sample into two separate tubes, label them with each bear’s name and the date of collection, and store them in a special freezer. Credit: Laurie Thompson/Smithsonian

On a routine basis, we send the samples to the endocrine lab at our Front Royal, Virginia, campus for analysis. In a male panda, our scientists look for the rise and fall in testosterone levels. For a female panda, they track her estrogen and progesterone levels. For example, when a female giant panda’s estrogen levels rise, it means she is in estrus—the very short (48-to-72-hour) window when female giant pandas are able to conceive a cub. After her estrogen levels peak, it indicates that she is ovulating.

By the end of April, Bao Li and Qing Bao went from checking in with each other every once in a while to spending all their time near the howdy window. We collected a urine sample from Qing Bao on April 30 and sent it to the lab. Sure enough, our endocrinologist confirmed that Qing Bao’s estrogens were high—she was experiencing an estrus cycle!

By May 6, the bears’ behaviors changed again. While they were still interested in one another and vocalized at times, they occasionally walked away. This indicated that Qing Bao was past her hormone peak. Eventually, both bears will get back into the groove of their normal routine.

Giant pandas Qing Bao (left) and Bao Li (right). Credit: Roshan Patel/Smithsonian

While it is normal (and very exciting) that Qing Bao experienced her first estrus, it doesn’t mean she and Bao Li are ready to breed. After all, they are young and still growing! Plus, males mature at a slower rate than females do and generally do not breed before 5 years of age. Although we are a couple years away from breeding, the fact they showed such positive interest in each other is a great sign for the future!

Get pandas in your inbox — sign up for our e-newsletter. Want to visit our pandas in person? Reserve your free Zoo entry pass here. Stay connected to Bao Li and Qing Bao from home on the Giant Panda Cam, sponsored by Boeing.

Related Species: