Biography

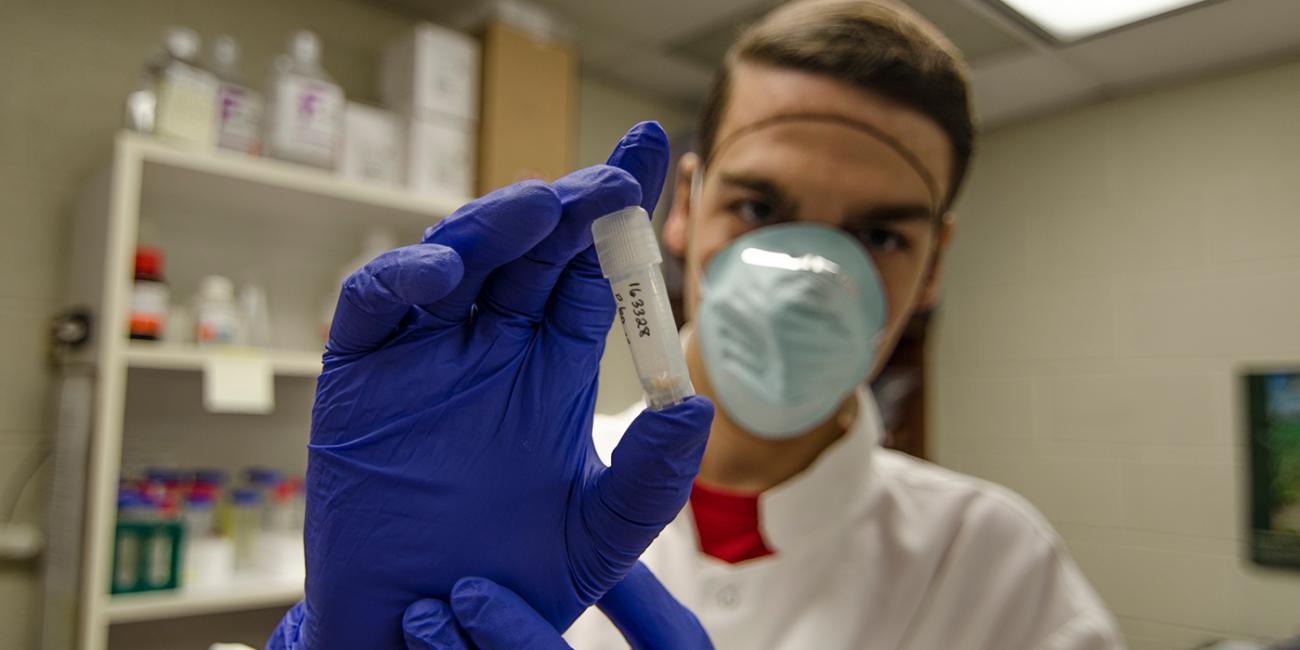

Rob Fleischer is senior scientist and head of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute's Center for Conservation Genomics. His primary fields of interest are evolutionary and conservation biology. He conducts individual and collaborative research in population and evolutionary genetics, systematics, and molecular and behavioral ecology, mostly on free-ranging bird and mammal species, and their pathogens. Many of his recent projects use genomic, transcriptomic and microbiome methods.

Fleischer has particular interest in:

the use of ancient DNA methods to document changes in genetic variation through time and phylogenetic relationships of extinct or endangered organisms (especially of the recently extinct Hawaiian avifauna);

the use of highly variable genetic markers to measure genetic structure and relatedness, and to ascertain mating systems, in natural populations;

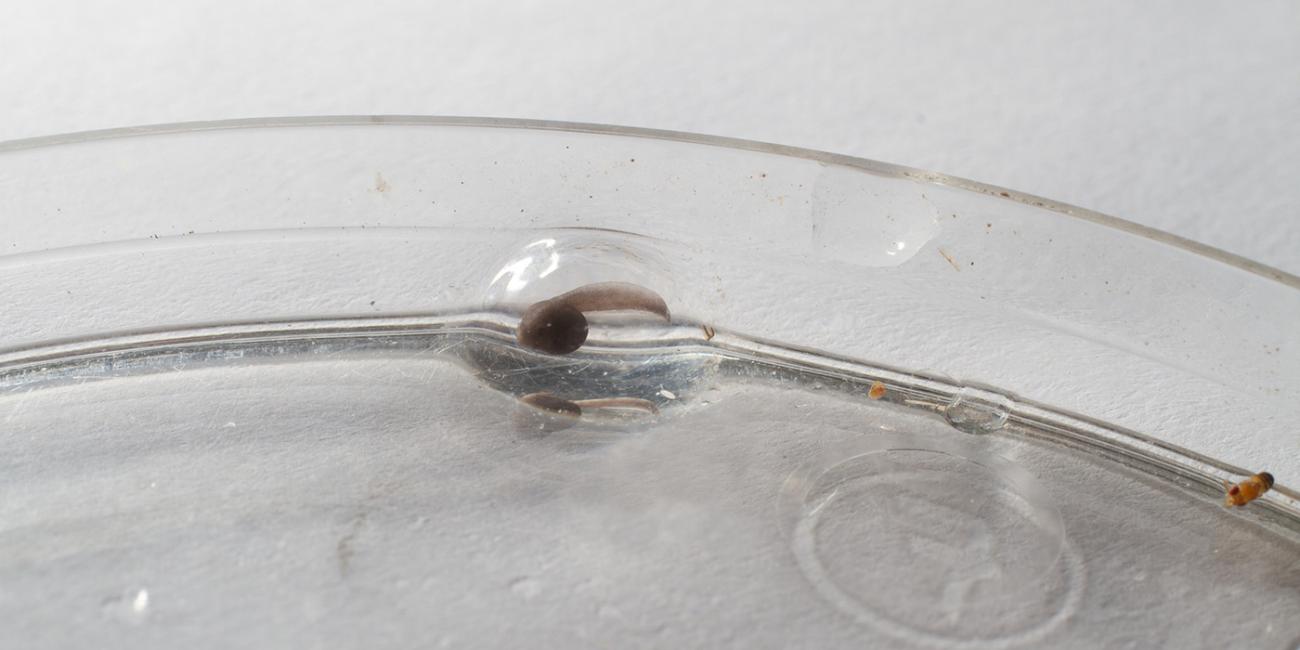

and the use of genetics to study the evolutionary interactions between hosts, vectors and infectious disease organisms (e.g., major projects on introduced avian malaria in native Hawaiian birds, invasive chytrid fungus in amphibians, and tick-transmitted pathogens).

Fleischer grew up in Southern California and attended the University of California, Los Angeles and the University of California, Santa Barbara. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in biology from UCSB in 1978 and received his doctorate in evolutionary biology from the University of Kansas in 1983. After two years of postdoctoral work at UCSB studying cowbird vocal dialects and genetic structure, he spent six years as university faculty before moving to the Smithsonian's National Zoo in 1991 to develop the Zoo's program in conservation genetics.

Fleischer has authored or co-authored more than 280 peer-reviewed contributions to scientific literature. His research program has been supported primarily via competitive grant and contract funding from National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and other federal and state agencies and foundations. Among other honors, Fleischer was named a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2003 and was the 2012 recipient of the William Brewster Medal of the American Ornithological Society.

Fleischer has been a rabid birder and naturalist since the age of 13. After taking a very illuminating and exciting genetics course as an undergrad at UCSB, he decided to merge his fascination with bird ecology and evolution with his newfound interest in molecular genetics, ultimately combining population genetic theory, fieldwork and molecular lab analyses. This synergy led to a career conducting and guiding students and postdocs in conservation genomics research.