Happy Amphibian Awareness Week 2023

'Hoppy' Amphibian Awareness Week! All week long, the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute will be sharing stories about amazing amphibians and the scientists working to save them from extinction.

Live Events

Join amphibian experts in-person on Sunday, May 7 at the Reptile Discovery Center from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. to kick off the Zoo's Amphibian Awareness Week celebration!

And on Thursday, May 11 at 2 p.m., check out a live, virtual program where guests will get an up-close look at a Japanese giant salamander, chat with an amphibian expert, and more! Click here to register.

Or, follow along on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter with the hashtag #AmphibianWeek.

May 7 | Hidden Biodiversity

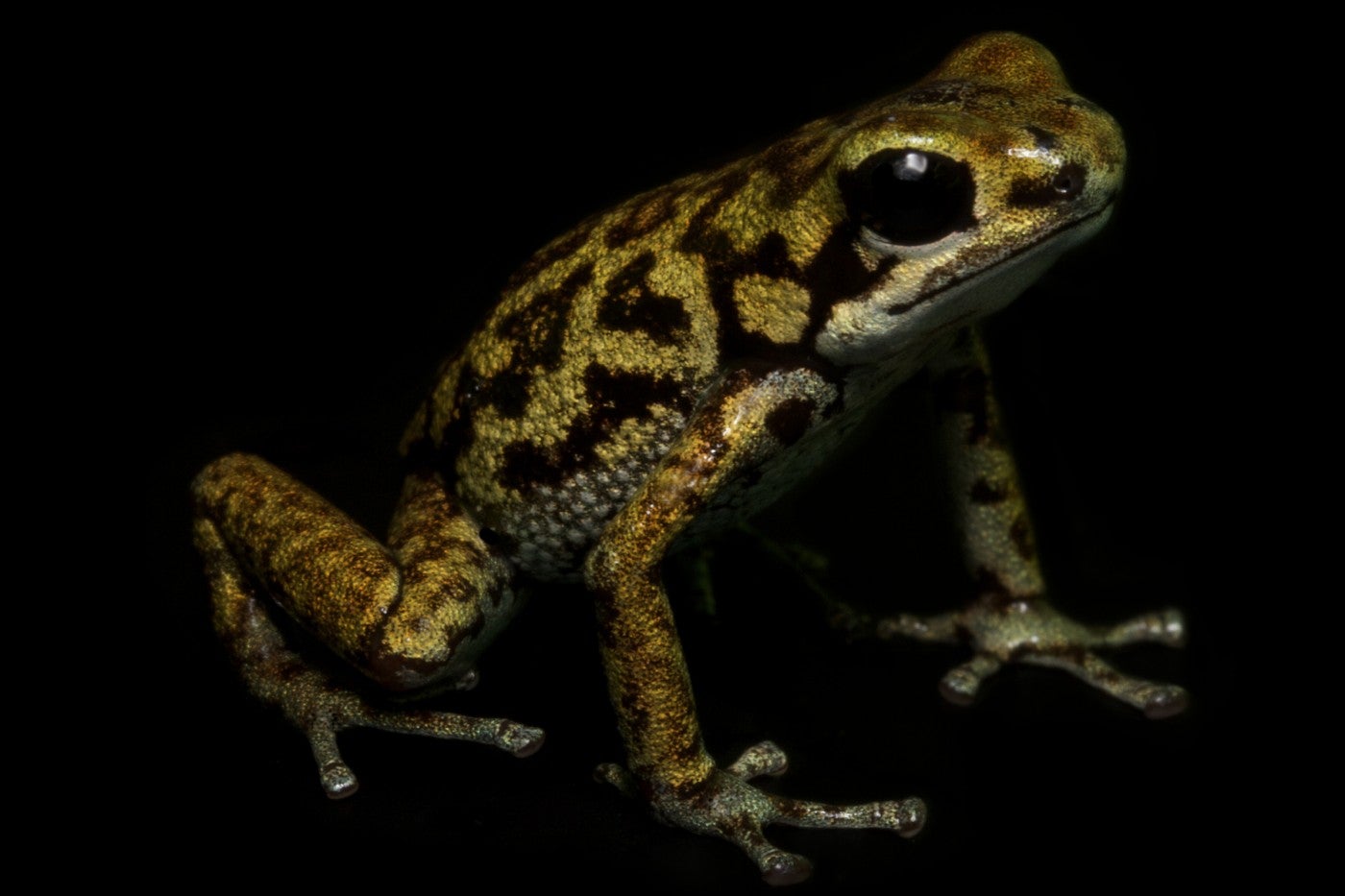

At our May 7 Amphibian Awareness Week kickoff event at the Reptile Discovery Center, you can watch a Japanese giant salamander feeding, meet a Vietnamese mossy frog and see if you can spot the unbe-leaf-able lemur leaf frog. While you're hopping between exhibits, meet these adorable amphibians along the way: Panamanian golden frogs, coronated tree frogs, tiger salamanders, red salamanders, red-backed salamanders and emperor newts.

Although eastern newts are aquatic as larvae and adults, juveniles (called red efts) live on land! Around 2 to 5 months of age, their lungs, legs and eyelids make them more suited to life on land. As they search for water, they make their homes in leaf litter along the way. Learn more about these cool critters.

May 8 | Amazing Amphibian Skin

As a scientist and intern at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute’s Center for Conservation Genomics, Lindsey Gentry's focus is on slime—specifically amphibian slime, and the creatures within.

What?! Things living in slime? On frogs? Yes, it’s true! Have you ever wondered what the difference between a reptile and amphibian is? Well, if you’ve ever picked up a frog or touched a lizard, you may have noticed they feel different. Skin texture is a key difference between reptiles and amphibians. Reptiles typically have rough and scaly skin while amphibians have moist and slimy skin. This moist and slimy skin is how amphibians, frogs, salamanders and caecilians breathe—some don’t even have lungs at all!

So, the sliminess on amphibians is more than just goop; it’s basically how these animals survive. The slime is also a great environment for bacteria and microscopic fungi to live. This community of microorganisms is called a microbiome. These microbiomes are extremely beneficial, and can defend an animal against disease, infection and more. However, anything that messes with this slime, messes with the ability of an amphibian to breathe.

Learn more about Lindsey's research here.

What’s in a name? The emperor newt’s moniker comes from the Mandarin words "shan" (mountain) and "jing" (spirit or demon). This highly toxic amphibian lives only in the mountains along a handful of rivers in western China. During the breeding season, they live in water fields, like rice paddies, ponds or humid grasslands. Learn more about them.

Poison frogs living in human care aren’t poisonous, thanks to a “detox” diet of mild insects, like crickets and fruit flies. Can adding alkaloids to a frog’s diet help it regain its toxins and get its “spice” back? The answer can help conservationists successfully reintroduce species that rely on toxins for survival to the wild says Luke Linhoff, post-doctoral research fellow at Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute and Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project.

For decades, scientists have wondered whether the key to saving frogs from the deadly chytrid fungus lies in their skin. Could they genetically modify bacteria found in the frogs’ mucus layer and boost its antifungal properties, in effect creating a “living pharmacy” on the frogs? Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute scientist Brian Gratwicke and partners set out to test whether probiotics could protect the frogs from their fungal foe.

Find out in this Q+A with Dr. Gratwicke!

May 9 | Eat and Be Eaten

Meet the cutest clump of “moss” you ever did see: the Vietnamese mossy frog! In spring 2022, the Reptile Discovery Center team celebrated the arrival of 50 hatchlings. That's a lot of frog mouths to feed! So, what do mossy frog tadpoles eat? Most tadpoles are foragers—they eat anything and everything. In the wild, mossy frog tadpoles prey on aquatic invertebrates and other smaller tadpoles. Here at the Zoo, their diet is protein-based, small invertebrates and aquatic fish food.

When tadpoles grow into froglets, what do they eat? Amphibians’ instinct to hunt is triggered by the movement of their prey. Although a mother mossy frog may weigh 40 to 50 grams, a newly-formed froglet may only weigh a gram or two! Small frogs need even smaller food. We feed our froglets live crickets that are tiny—about the size of a pinhead. To hunt, they leap on top of their prey, grab it and shove it into their mouth. It’s not the most graceful behavior, but it’s fun to watch!

As the frogs grow, the prey they receive increases in size, too. Zoo visitors might not realize that Reptile Discovery Center keepers don’t only take care of the animals in our collection. We also have to feed and care for their food, too!

Many salamanders are ambush predators. The bigger, bulkier species tend to lunge at prey. Smaller species—including long-tailed salamanders and cave salamanders—have a different strategy. With prey in its sights, a salamander quickly contracts its muscles, causing the hyoid bone in its mouth to protrude. In the blink of an eye, the salamander’s elongated, sticky tongue has secured its meal. The speed with which they capture their prey is amazing. The northern red salamander can extend and withdraw its tongue in just 11 milliseconds!

May 10 | Amphibian Communications

Panamanian golden frog males attract females with visual displays, instead of calling like most male frogs and toads do. These attractive displays include leg and head twitching, stamping the ground and hopping in place. Male frogs often wave their arms to communicate with females whom will wave back if interested.

May 11 | Amphibians Through Time

It's Amphibian Awareness Week! On Thursday, May 11 at 2 p.m. EDT, celebrate with an up-close look at some of the Zoo's salamanders and chat with an amphibian expert. This live, interactive virtual program is free and includes live captioning and ASL interpretation. Register here.

May 12 | Amphibian Art and Culture

Learn why frogs matter and how you can help frogs from our colleagues at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

May 13 | Action for Amphibians

Amphibians—animals that live in water and on land—need specialized habitats, atmospheres and food in order to thrive. Leap into learning what it takes to care for some of the frogs found at Smithsonian’s National Zoo from Matt Evans, assistant curator of the Reptile Discovery Center. Read the update.

How do frogs survive, thrive and breed in the wild? Armed with tiny radio transmitter “backpacks,” these Limosa harlequin frogs are helping Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute scientists better understand amphibian lives in Panama’s rainforest. Partners at the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project help us keep track of the frogs’ movements. Learn more about their research.

Welcome, salamander seeker! If you didn’t know you needed to be a salamander seeker, you do now. You don’t need to be a scientist or a naturalist to find a wild salamander, all you really need to do is find the right rock.

As a molecular ecologist at the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute’s Center for Conservation Genomics, salamander spotting is one of Carly Muletz Wolz's favorite ways to get people excited about animals in nature. To her, there is nothing more exciting than helping someone find a salamander for the first time. With just a few tips and tricks, anyone can find salamanders and celebrate nature in their local area.