Uplifting Stories: Spring is for the Birds

From the arrival of adorable chicks to award-winning excellence in animal care, much is brewing behind the scenes at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. In celebration of World Migratory Bird Day May 9, the bird care team share some of their favorite stories from April 2020 that have all of us soaring to new heights.

In fall 2021, the Smithsonian's National Zoo’s historic 1928 Bird House will transform into a first-of-its-kind attraction that immerses visitors in the annual journeys of western hemisphere birds. Learn more about this exciting project!

Stanley Crane Alice | Smithsonian’s National Zoo

Stanley crane Alice is unlike any other bird of her species. Hand-raised by keepers, she has a sweet temperament and joyous personality. When she sustained a leg injury last summer, animal care staff rallied around Alice and found an innovative solution to help her thrive. Keeper Debi Talbott shares the remarkable story of Alice's road to recovery. Read her update.

2019 Plume Award Winner | Smithsonian’s National Zoo

The Smithsonian’s National Zoo’s historic Bird House may be under renovation, but that has not stopped the animal care team from bringing native shorebirds, songbirds and waterfowl under their wing to establish best practices in husbandry and breeding. Last year, keepers celebrated many significant hatchings behind the scenes—including flamingos, wood thrush, scarlet tanagers, indigo buntings and a band-tailed pigeon.

For their efforts to propagate these species, the Bird House team recently received the prestigious Plume Award for “Achievement in Avian Husbandry.” This honor was bestowed by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ Scientific Advisory Group in recognition of the team’s expertise and skills to aid in the recovery of threatened and endangered Western Hemisphere migratory bird populations.

As threats to migratory birds in North America intensify and bird populations decline, there is a growing interest among zoos in the conservation and management of native songbirds. Bird House keepers are developing the husbandry and reproductive programs for North American migratory songbirds. By working to understand their needs, the Zoo stands ready to offer assistance to populations in decline as well as contribute to the understanding of common birds. Cracking the code of breeding these species in human care while they are still common is vital for future conservation efforts.

Band-Tailed Pigeon | Smithsonian’s National Zoo

Peep, peep, hooray! Our Bird House team recently welcomed a band-tailed pigeon chick, or “squab,” April 14. This is the second squab for its 3-year-old mother and 2-year-old father. Their first squab, a male named Flash, hatched in July 2019. Keeper Shelby Burns shares the secret of their success.

“Band-tailed pigeons are beautiful birds with a lot of personality! To set the mood for breeding, we built the pigeons’ exhibit with their natural habitat in mind. This entailed offering them plenty of places to perch, vegetation to hide in and UVB lights to bask under. We also gave them several nesting location options and materials, including coconut fibers and pine needles. This pair learned from their last successful hatching and created an even sturdier, more intricate nest by adding pine needles and molted feathers.

“Mom laid an egg March 27, and both she and dad took turns incubating it. Dad took the morning shift, and mom relieved him of his duty in the afternoon and evening. Band-tailed pigeons typically incubate for 16 to 22 days. This squab hatched right on time: day 18. This pair has continued to learn and improve their parenting skills. Both mom and dad are very attentive to the squab and take turns feeding it crop milk. In less than a month, it will fledge from the nest. We are excited that this family continues to grow, and we look forward to guests meeting them in our Bird Friendly Coffee farm aviary when the Bird House opens in fall 2021!”

White-Naped Crane | Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute

White-naped cranes Brenda and Eddie are parents again! Their fourth chick, a female, hatched April 2 at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. This chick is the 46th white-naped crane to hatch at SCBI. Prior to hatching, scientists confirmed the chick’s sex using DNA samples taken from inside of the egg. Keepers report Brenda and Eddie are providing excellent care to their chick.

Bird keepers have had great success producing chicks from cranes that have behavioral or physical impediments that prevent them from breeding. The chick’s parents are one of the only white-naped crane pairs living at the research facility capable of breeding naturally. There are an estimated 5,000 white-naped cranes living in the wild, and the species is listed as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Blue-Billed Curassow | Smithsonian’s National Zoo

Keeper Heather Anderson cares for many rare species at the Bird House, including a pair of blue-billed curassows. Native to Colombia, these birds are considered critically endangered; scientists estimate only 300 to 800 individuals remain in their native habitat. Anderson reports that this pair has a strong bond, and keepers are hopeful they will produce a chick.

Meantime, she is training them to voluntarily participate in their health care. When she enters the exhibit, she cues the curassows to “station” (stand still) on a stump. This allows her to examine the birds closely and look for any signs that they may need medical attention. Once a month, she places a scale on the stump so that when they “step up” she can monitor their weights. The male currently weighs 8 pounds, and the female weighs 6 pounds.

Guam Kingfisher | Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute

Guam kingfishers are small, sassy and the most endangered animals in the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s collection. With only approximately 135 Guam kingfishers remaining in the entire world, every chick is precious. SCBI’s bird team recently celebrated the arrival of two chirping chicks, which hatched April 21 and 23. They are the first offspring for 11-month-old father Animu (ah-KNEE-moo) and 2-year-old mother Giha (GEE-ha). To assist the new parents, keepers are allowing them to raise the older chick, a female, while animal care staff hand-rear the younger, a male. These two healthy, thriving chicks bring the total number of kingfishers under SCBI’s care to eight. Learn more in keeper Erica Royer’s update!

American Avocet | Smithsonian’s National Zoo

Mealworms are on the menu for the Zoo’s American avocets. To help them acclimate to sharing a space with their caretakers, keeper Lori Smith crouches a short distance away. She tosses the tasty snacks onto a placemat, and the avocets gobble them up. Feeding the birds at a close proximity enables Smith to gain their trust. If they associate keepers with a positive experience, the birds will be calmer when it comes time for staff to enter the habitat for feeding, cleaning, husbandry training or veterinary procedures. It is also a useful tool for keeping tabs on the birds’ health, including their eating, bathing and preening habits.

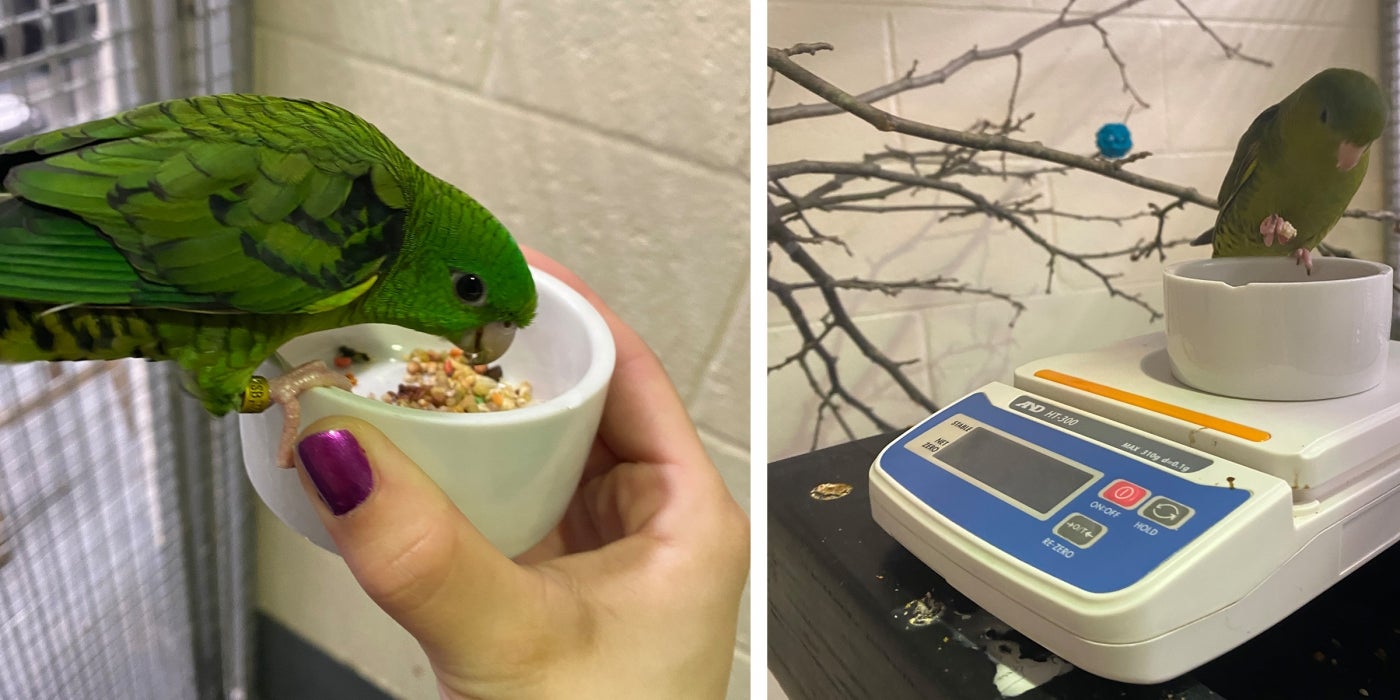

Barred Parakeet | Smithsonian’s National Zoo

When a flock of birds shares an enclosure, how do keepers ensure each individual is getting his or her share of food? In the case of our six barred parakeets, keepers offer them “high value” diet items—foods that are considered treats—in the morning, when the birds are most eager to train. As the parakeets land on their food bowl, keepers gently place it on the scale and record the bird’s weight. If a bird has lost or gained weight, keepers work with the Department of Nutrition Sciences to increase or decrease that individual’s diet.

Redhead Duck | Smithsonian’s National Zoo

The Bird House's redhead ducks share their exhibit, pool and food with some colorful neighbors—flamingos. Normally, the ducks will sit right underneath the flamingos while they're feeding and catch any pellets that drop. In this photo, the female (left) is diving for food, while the male (right) is taking a bath.

To monitor the ducks’ health without disturbing the other birds, keepers have trained them to come inside for a physical (and some treats) on cue. The training that keepers do with the Zoo’s ducks is called "shifting"—they cue them to move from one area to another, usually from the outdoor exhibit to an indoor enclosure. As with most training sessions, food is a big motivator, and ducks are no exception! Keepers stand in the indoor enclosure and use a high-pitched duck call. Once inside the enclosure, the ducks are rewarded with their diet-pellets, meal worms and wax worms. They also get crickets, which are a treat for them.

This story appears in the May 2020 issue of National Zoo News.