Why Do Animals Eat Poop? (And Why It Might Be a Good Thing)

We’ve all seen animals eat poop. Usually, we think it’s pretty gross. Some animals, such as dung beetles, focus their entire lives around finding and eating feces. But why do so many animals, from rabbits and dogs to salamanders and lemurs, show this behavior? Despite the common idea that eating poop is a bad sign, it is actually a natural behavior for many animals. While we generally do not recommend it for anyone reading this article, we are here to explain why eating poop can sometimes be good for animal health and how the practice is even becoming an important part of human and animal medicine.

Is there a word for eating poop?

Dung. Feces. Stool. Excrement. We have many words for poop. And there is indeed a word for eating it. “Coprophagy” (pronounced cop-roe-fay-jee) is the scientific term for ingesting feces. The word dates back to the 1800s and has Greek origins, combining the terms “kopros” (dung) and “phagos" (eating). There are even specific terms for eating one’s own feces - “autologous (ah-tall-o-gus) coprophagy” - versus eating the feces of another animal - “non-autologous coprophagy.”

Is eating poop dangerous or a sign of illness?

The short answer: Sometimes, yes, but it’s complicated. Eating poop can spread diseases and parasites, so coprophagy is not always a good thing. This is one of the main reasons why humans think eating poop is disgusting. We have adapted to avoid feces because of these potential dangers.

Coprophagy may also be part of a response to disease or stress. Eating feces might mean that the animal is lacking nutrients, not digesting their food properly, or experiencing psychological distress. It could also indicate the presence of a parasite that is stealing nutrients and energy away from the animal. This may be particularly true if an animal suddenly starts eating feces when it has never done so before. So, noticing when an animal is eating poop is important for pet owners and veterinarians.

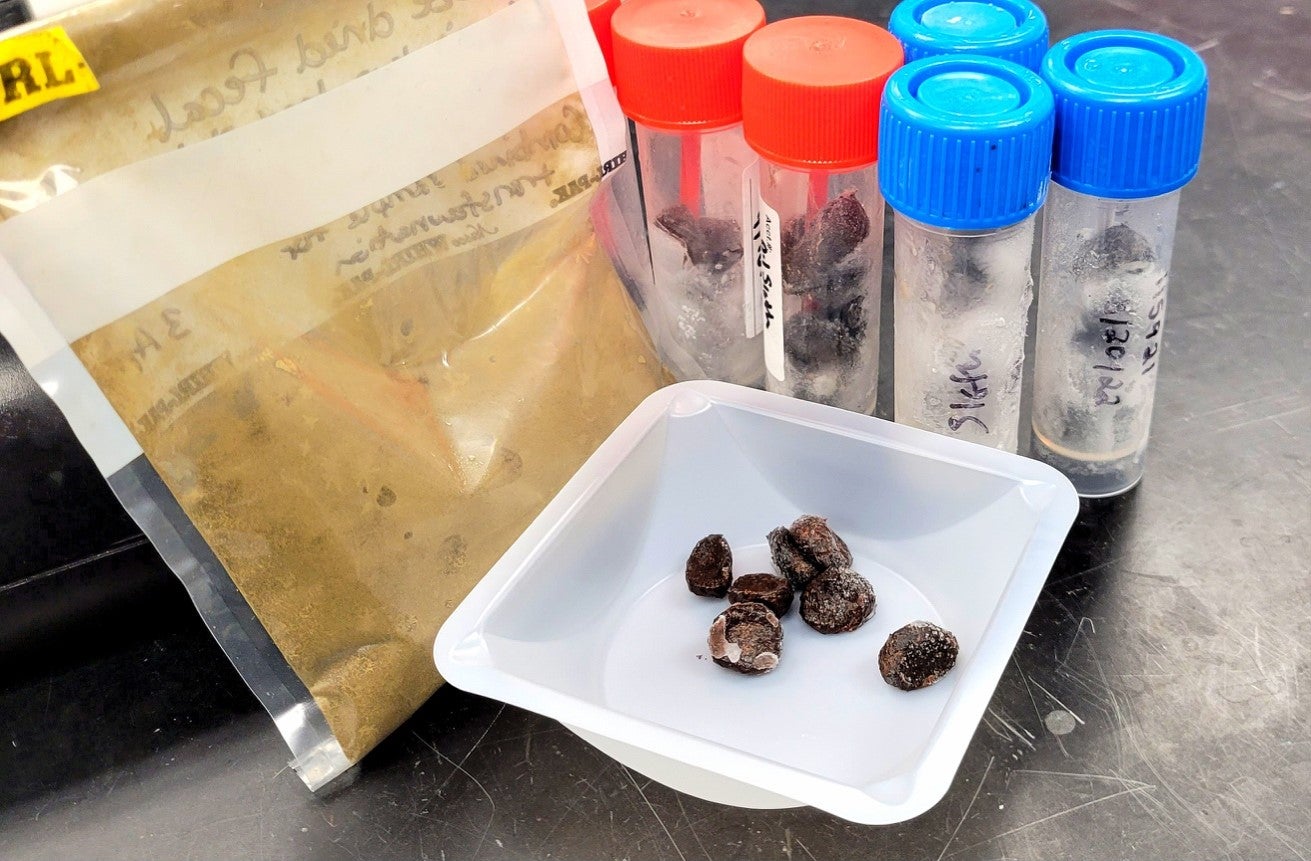

Cheetah feces attracting insects that feed on the poop.

Then how can eating poop be good for an animal’s health?

There is more to poop than meets the eye. Some animals, like rabbits, can even become sick if they don’t eat some of their own poop. Poop has four important components, each of which can contribute to it being a good thing to eat: 1) water, 2) undigested food items, 3) the animal’s own tissues and fluids, and 4) gut microbes.

The first component, water, can be important for animals that live in dry climates and need to maximize their hydration. In desert mice, for instance, nursing mothers will eat their young’s feces to regain some of the water lost through lactation. The second and third components can act as food, providing valuable nutrients, vitamins, and minerals that the animal gets during the second round of digestion. Rabbits are a classic example of an animal that redigests their feces to extract more nutrients from their plant-based diet. The fourth component, microbes, includes important microscopic organisms that originate in the animal’s gut tract. These microbes can help with digestion and prevent disease. They are also one of the main reasons for studying poop.

Why do gut microbes matter?

Over millions of years of evolution, all animals, including humans, have formed important partnerships with their resident gut microbes. These invisible partners have evolved along with us, and they help maintain our health by interacting with virtually every bodily system. The trillions of microbes living in animal guts can help their host digest food, regulate metabolism, reduce inflammation and prevent disease. They can even play a role in behavior, with some gut microbes linked to specific moods and food cravings (think about that next time you’re yearning for chocolate cake). Without these microbes, animals would be unhealthy and struggle to survive. So, keeping these microbial communities balanced and healthy is an important part of taking care of our zoo animals. (Check out the Microbes Matter blog and the Microbiomes and Metagenomics page for more information on microbiomes.)

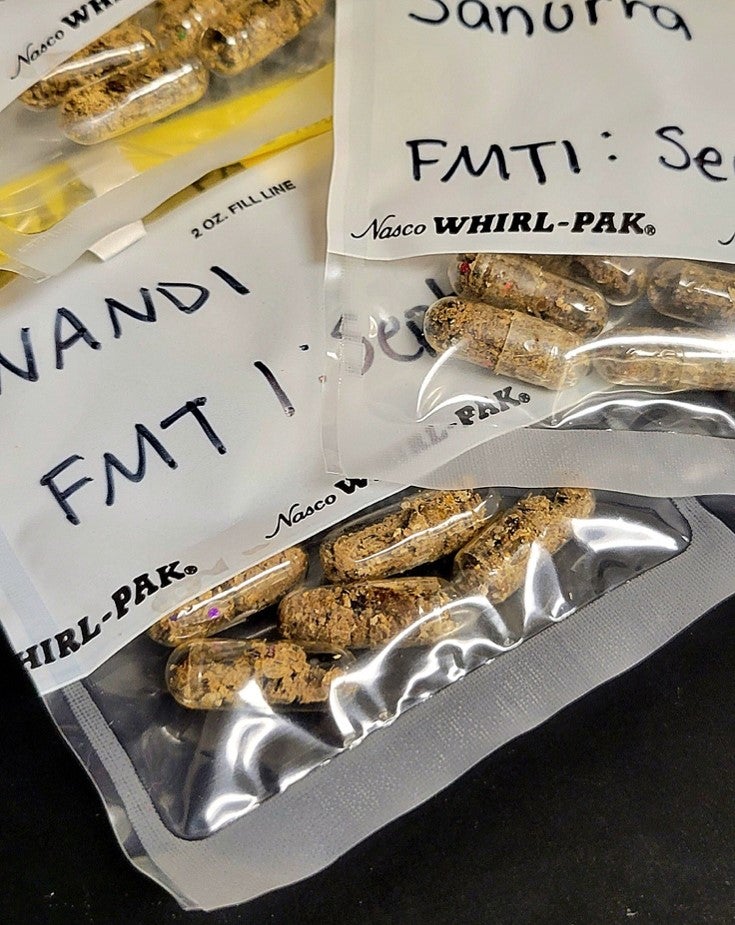

Poop pills used for fecal transplants in cheetahs.

Why and how is poop being used in human and animal medicine?

Doctors and veterinarians across the ages have been intrigued by the fact that so many animals eat poop. In fact, poop has been used as a treatment in human medicine for at least 3,500 years and in veterinary medicine for at least 2,000 years. Most of those ancient medical practices seem absurd today. Using crocodile dung to restore hearing loss (as ancient Egyptians believed) is pretty unappealing and unlikely to work. Yet poop is making its way into modern medicine in an unusual form: poop pills, technically known as fecal microbiota transplants.

The premise of fecal transplants is simple. If you take a healthy, diverse microbial community from the feces of one individual, and transplant it into the gut of an unhealthy individual, the incoming microbes can replenish the community and combat disease. In human medicine, fecal transplants are best known for treating Clostridioides difficile, a terrible gut infection that often doesn’t respond to antibiotics and can be fatal in severe cases. After decades of fighting this disease without much progress, doctors tried adding beneficial microbes to the guts of infected patients though fecal transplants. Since then, the successful use of fecal transplants has revolutionized treatment for this disease. We’ve all heard of blood banks and, now, there are “stool banks” devoted to providing healthy, donor poop for fecal transplants.

How are we using poop as medicine at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute?

Luckily, getting animals to eat poop is often a lot easier than getting humans to do so. And all the benefits that fecal transplants can have for humans also apply to animals. Microbial ecologists and animal nutritionists study poop to learn how we can use it to improve zoo animal health (learn more about non-invasive poop research). For example, we recently used fecal transplants to help a Zoo sloth that was experiencing frequent and abnormal stools. Sloths normally poop about once a week, but this individual was defecating almost once a day, far too often for a slow-moving sloth! The fecal transplants changed the sloth’s microbiome and helped get her poop cycle back to normal (learn more about this project in the published paper). We are also investigating whether fecal transplants can be used to better prepare animals like black-footed ferrets for reintroduction into the wild. By identifying ferrets that are better at adapting to the natural environment, we can use their poop as transplant material for ferrets who might need a microbial boost to help them in their new environment.

But since poop can sometimes transmit diseases as well, we need to be careful as we apply these microbial treatments. At the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, our team of scientists, nutritionists, veterinarians and animal care professionals work together to determine best practices for the use of poop as medicine for our animals. So next time you see an animal eat poop, consider the possible benefits and remember that eating poop pills can save lives (and maybe species).