Rewriting Frogs’ Future with Science

Stories about amphibians don’t always end with “happily ever after,” but scientists around the globe — including Brian Gratwicke at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute — are working together to rewrite frogs’ fate. Their foe? The deadly chytrid fungus — which can cause the frogs’ untimely deaths.

In this Q&A, Gratwicke talks about how scientists are sharing their observations about chytrid in an effort to better understand the disease’s impact and prevent future extinctions. The study, entitled “Amphibian fungal panzootic causes catastrophic and ongoing loss of biodiversity,” was published March 29, 2019 in the journal Science.

How did chytrid spread all over the world?

When we look at the genomics of the chytrid fungus, the highest genetic diversity of Batrachochytrium exists in Southeast Asia — so, that area is likely the center of evolutionary origin of this species. The global pandemic strain of the fungus has spread around the world, likely through the trade of amphibians for food or for pets.

Does chytrid affect all frogs equally?

The frogs that have co-evolved with this fungus are less likely to have severe impacts from the disease. But, when the disease gets into new world frogs, like those found in Australia, Central America and South America, the frogs are badly affected.

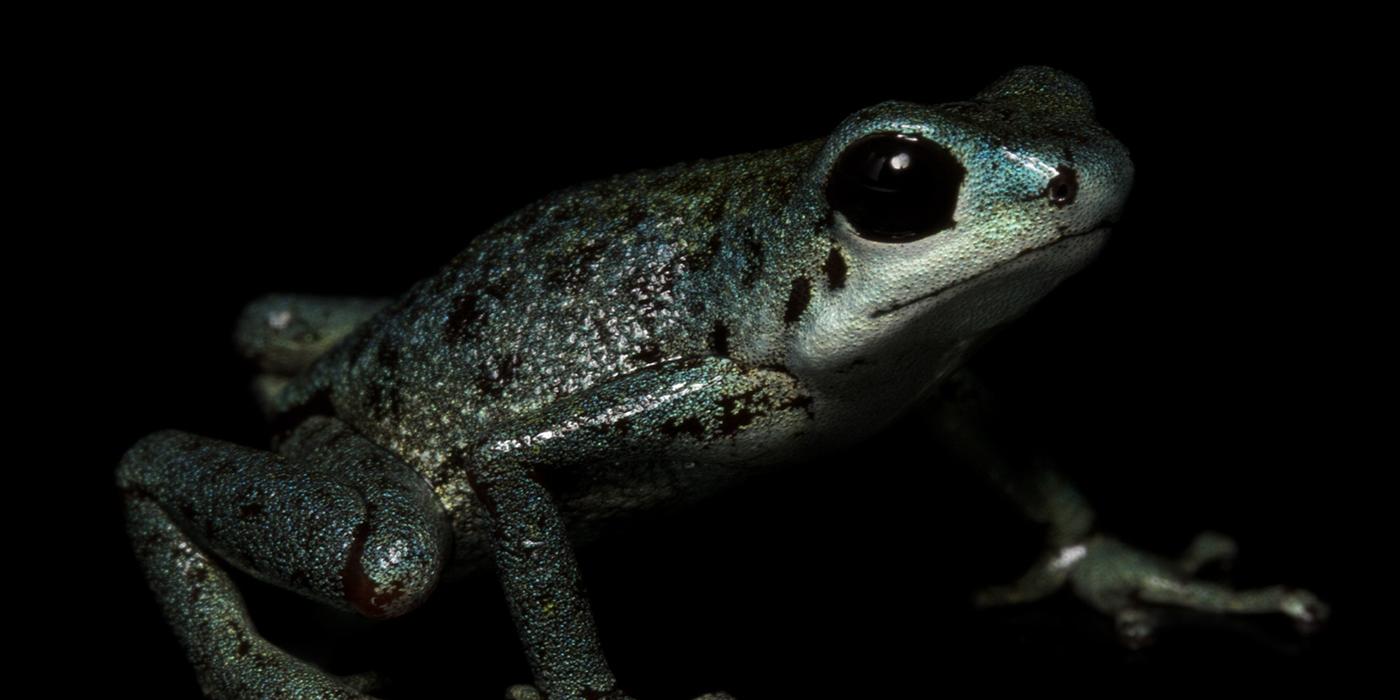

Limosa harlequin frogs (Atelopus limosus), which are native to Panama, are among the species most affected by the chytrid fungus.

Why do some frogs fare better around chytrid than others?

Some species secrete anti-fungal chemicals, and some also have symbiotic bacteria living on their skin that also secrete anti-fungal chemicals. It appears that certain groups of frogs really don’t have very good protection against the disease. One group that I work with in Panama is Atelopus, or harlequin toads. They are very, very susceptible to the disease.

Why look at global populations rather than specific species?

The trouble with the amphibian chytrid story is that it is a lot of stories. For example, where I work in Panama is ground zero of amphibian declines from chytrid fungus. But perhaps in other areas of the world, their experience has not been as bad.

This study provides context and helps synthesize hundreds of thousands of hours of first-hand research all over the world so we can take stock of the cost of this disease. The first amphibian disappearances attributed to the chytrid fungus began in the 1970s. Peak declines appear to be around the early 1990s. We wanted to evaluate how severe the declines have been, and what animals we have lost on a global scale. Doing so paints a finer picture of where frogs are disappearing.

We speculated that this disease has been devastating, but now we have quantified it. We found that 90 frog species have gone extinct because of this pathogen, and more than 500 others are declining.

What are scientists doing to save frogs?

The good news is, there are some instances where frogs seem to be recovering. Initially, it was unclear as to whether the frogs were going to recover or evolve in some way. It appears that there are species across the phylogenetic tree that are seeing some recovery, and that is really encouraging. In fact, it is the basis of the next step we are taking in our research at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo.

What are the next steps?

We are looking at frog skin secretions to determine how effective they are at fighting chytrid fungus. We give the frog a bath in water, and then take that water and add chytrid fungus to it. We can quantify how anti-chytrid a frog’s skin secretions are depending on what percentage of the spores are killed. If we are able to identify frogs that best resist the fungus, we can then selectively breed frogs with more anti-fungal skin secretions.

How do you test for chytrid?

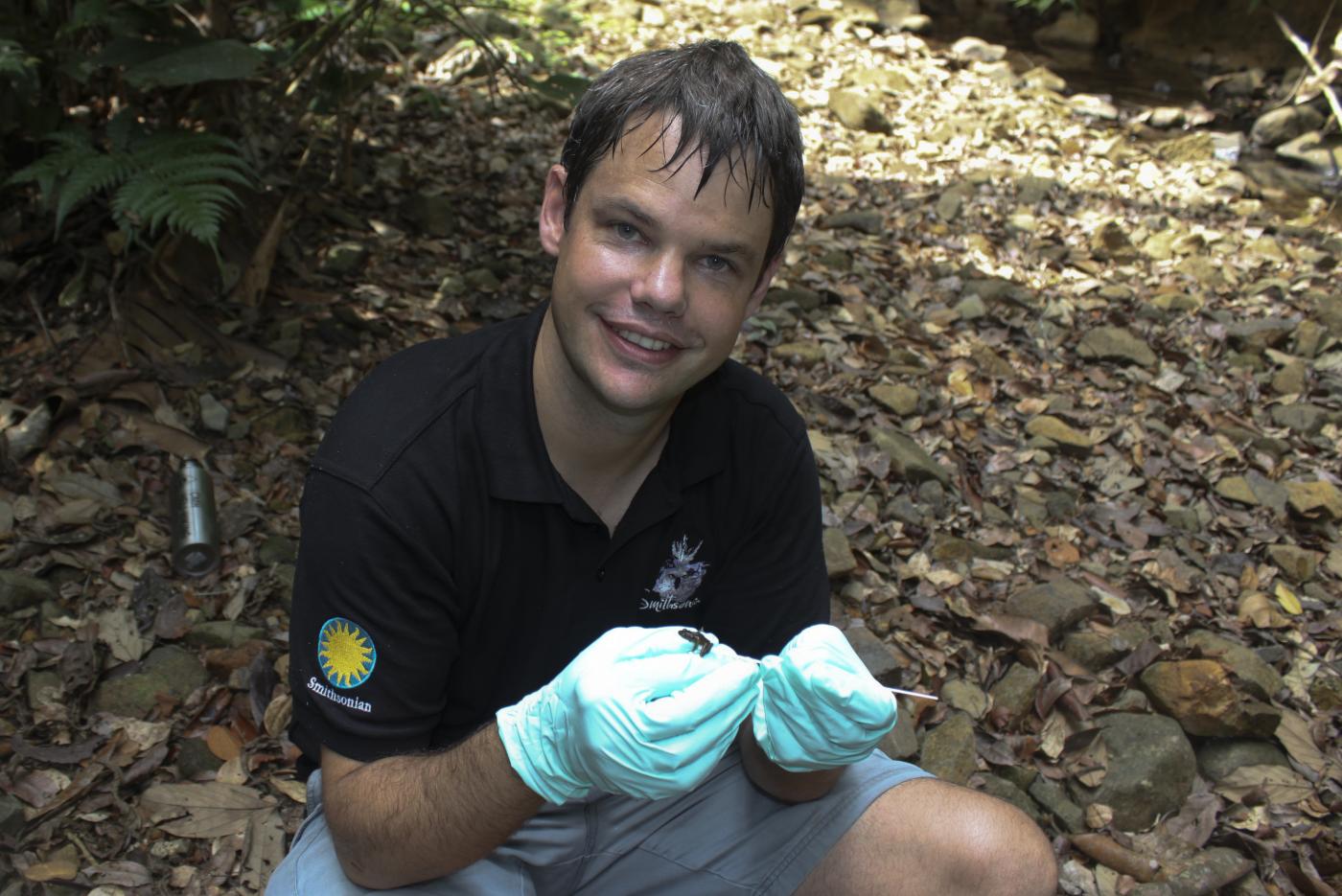

To test for the fungus, we rub a sterile swab over the frog’s skin, then bring the swab to a genetics lab for testing. The more chytrid DNA we find on a swab, the more heavily infected a frog is.

What happens if a frog tests positive?

Any frog in our collection that tests positive for chytrid receives an anti-fungal treatment. We place them into a bath containing anti-fungal solution for 10 minutes, and repeat this step every day for 10 days.

This amphibian rescue pod in Panama is home to an assurance colony of critically endangered frogs. Gratwicke and his colleagues at the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project are working to develop methodologies that will reduce the impact of the amphibian chytrid fungus. They hope to reintroduce the frogs under their care back to the wild.

What makes you optimistic about frogs’ future?

I am fortunate to work with colleagues who understand the gravity of being good stewards of the environment. They dedicate their lives to ensuring these creatures have a future. There is a lot that we still have to learn, but I am feeling optimistic about the future. We have been trying very hard to find a cure for this disease. Maybe the antifungal secretions from frog skin will help be a tool that leads to a breakthrough.

As part of the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project, we have spent the last 10 years building a solid collection representing 12 frog species that are either highly threatened or endangered due to the chytrid fungus. Having these resources means that, over the next 10 years, we are well-positioned to better understand this disease, find a cure for it and begin reintroducing frogs back into the wild.

This story appears in the April 2019 issue of National Zoo News. Follow the latest frog research from Dr. Gratwicke and his collaborators. During your next visit to the Zoo, stop by Amazonia and the Reptile Discovery Center to meet our amazing amphibians!