Guam Kingfishers: A Truly Rare Breed

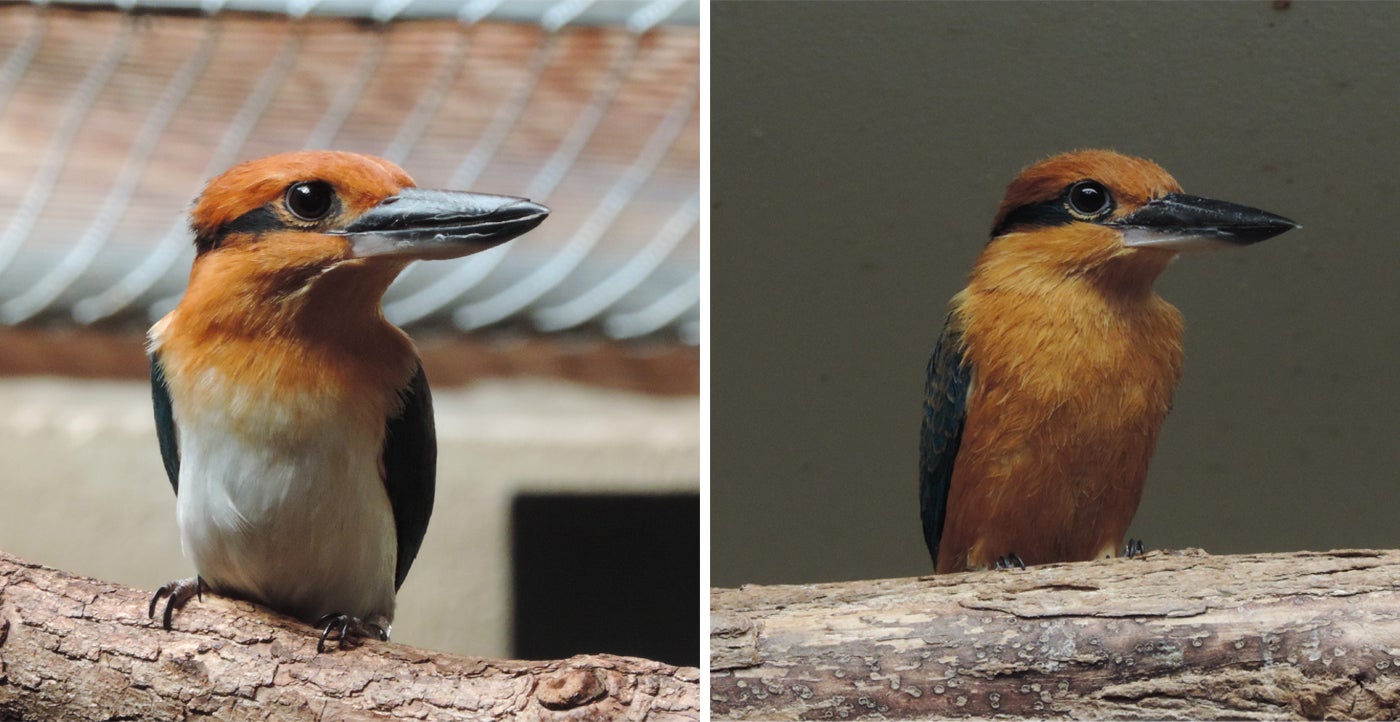

Some of my favorite birds to work with at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute are small but sassy, and Guam kingfishers certainly fall into this category. When animal keepers enter their enclosures to feed them, the birds go into full threat-mode. Guam kingfishers are notoriously territorial, and despite their small size, they are full of attitude. They flatten their small, robin-sized bodies like tiny torpedoes in what we call a “horizontal threat posture.” They aim their long, pointed bills toward us and watch our every step to make sure that we know they mean business! Females are a little larger than males and have white feathers covering their chests and abdomens, while males have orange. Both sexes are strikingly beautiful with rings of blue around their orange heads, and bluish-green backs and wings that shimmer in the sunlight.

Breeding season for the Guam kingfisher is typically December to August, and we have three pairs to introduce this year. So, we have our work cut out for us. Historically, Guam Kingfishers have been difficult to breed for multiple reasons, one of which is mate compatibility — a fancy way of saying they are very picky about whom they will breed with. As an animal keeper, I spend a lot of time observing the birds and assessing whether they are compatible and ready to be paired for breeding. The survival of the species rides on the production of new and healthy offspring, but no pressure!

The Guam kingfisher is known as the “sihek” (see-heck) in Chamorro, the native language of the Marianna Archipelago, and is the rarest species we have here at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Virginia. This bird is classified by the IUCN as extinct in the wild — meaning not a single wild Guam kingfisher exists. The last remaining 29 birds were captured in the 1980s and taken to zoos to try to save the species. It is a sad, but all too common story: When brown tree snakes (Boiga irregularis) were accidentally brought to Guam on military cargo ships and planes after World War II, they quickly wiped out 10 of the 12-13 species of birds on the island. Today, the only remaining forest birds on the island of Guam are the Micronesian starling and the Mariana swiftlet.

This accidental introduction of brown tree snakes caused an ecological disaster on Guam. Think of an ecosystem like a puzzle, where each plant and animal is a puzzle piece. Now, imagine how incomplete that puzzle looks when you start to take pieces away. All the birds that are now missing from Guam served their own important purpose within the ecosystem. The Guam kingfisher helped keep the insect and lizard populations in check. With birds removed, populations of insects, and particularly spiders, have increased to the point that people often carry walking sticks to clear the way of spider webs. Forests are also becoming thinner or disappearing, because there are few seed- or fruit-eating birds to consume and spread the seeds of the trees. It’s important that we try to replace as many pieces of this ecosystem puzzle as we can, and the Guam kingfisher is one.

Today, there are only 140 Guam kingfishers in the entire world, all within zoological facilities dedicated to bringing them back from the brink and one day returning them to the wild. SCBI has six of these rare and special birds — and hopefully more after this breeding season!

Guam kingfishers are part of an Association of Zoos and Aquariums Species Survival Plan (AZA SSP) which means they are all managed as a single population. An SSP coordinator makes recommendations about which males should breed with which females to make a genetically healthy population, and zoos send their birds to other zoos based on those recommendations. Needless to say, the birds don’t always agree with our matchmaking!

We know a lot about Guam kingfisher breeding behavior, but there is still much to learn. We see compatibility issues between some pairs but not others, and we are still trying to find out why. Because Guam kingfishers disappeared from the wild so quickly, there wasn’t much time to study them in the wild. We didn’t know much about their breeding behaviors. For example, we knew that the birds are cavity nesters, meaning they lay their eggs not in nests but in the holes of trees.

However, we didn’t know that the creation of the cavity is an important part of the courtship process. That’s something we learned over time. Now, rather than giving the birds empty nest boxes with premade holes, we allow them to excavate their own cavities and choose from a few different materials. We have tried logs with mulch-filled cavities, wooden nest boxes packed with mulch and wooden framed boxes with thick sheets of cork.

The cork nest boxes are typically the birds’ favorites. It makes sense, because this material would be most like the density of the coconut palm trees that they would have excavated in the wild. This year we will also be collecting fecal (or poop) samples throughout the breeding season. We can use these samples to monitor the birds’ hormone levels, and we hope that we can find correlations between their reproductive hormones and their compatibility.

When we introduce two birds, we hope to see them sitting close to one another in relaxed postures. Even more promising are those that immediately begin making a nest cavity together. When pairs are not compatible or not ready to breed, they tend to spend more time apart and display threat postures toward each other. These postures include bowing the head, pointing the bill toward the sky, holding the wings open while perching, or sitting up straight with the belly pushed out (so that their body looks like a little pear). Sometimes we even see bill sparring, which is when birds lock bills and fight. If we see that, we separate the birds for a time-out and reevaluate.

When a breeding introduction is going very well, the pair will sit close together and make soft warbling vocalizations that slowly build in volume. The louder calls are often associated with excavation. The birds will perch on a branch about 2-6 feet away from a nest box or log and take turns flying at the nest location, hitting it with the pointy tip of their bill. When they take off from the branch, they make a short but loud squawk before they hit their target.

Female Guam kingfisher Giha (left) and male Guam kingfisher Animu (right).

Unlike a woodpecker that perches on a tree and hammers away at a cavity, kingfishers can only hit an excavation site by catapulting themselves off a perch. This is due to the configuration of their toes, which is called “syndactyl” (sin-dak-till). It means that two of their forward-facing toes are fused, which makes clinging to a tree (like a woodpecker does) difficult. After kingfishers hit their mark, they return to their perch and do it all over again. Breeding pairs make several cavities in different locations before choosing one in which to lay their eggs.

Male kingfisher “Animu” (ah-knee-moo), which means courage or spirit in Chamorro, and female “Giha” (gee-ha), which means to guide or point out the way in Chamorro, are our youngest breeding pair. We saw immediate interest when they were housed side by side. They would perch next to each other on either side of the mesh throughout the day — certainly a good sign for their upcoming introduction. When it’s time to introduce a pair of birds, I retreat into a camouflaged tent where I can observe the birds without disruption. From my hiding spot, I watch for their initial reactions, which could range from total disinterest or love at first sight to bitter rivals.

When we opened the door between our youngest pair, it was Animu who entered Giha’s enclosure first. Giha, however, had other ideas and quickly chased him off. The young male took the hint and left! He quickly became distracted hunting for crickets. Luckily, it only took a couple of introductions for these love birds to become inseparable. Now, every time we check on them, we see them perched within 1 foot of each other. Animu was hand-reared by SCBI keepers in 2019 when his parents displayed behaviors that were not conducive to chick-rearing. We all look forward to the day when he can hopefully raise his own chicks.

With two more pairs to introduce this year, we will have many more updates to share. Stay tuned to learn more about our birds, and keep your fingers crossed that the couples decide that we have made the right match!

Help support the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute's efforts to preserve extinct in the wild Guam kingfishers by donating to Conservation Nation, an initiative of Friends of the National Zoo.

Related Species: