Fantastic Beasts of the Great Plains

Big, brown and beautiful is perhaps the best way I can describe an American bison. Male bison can weigh more than 2,000 pounds, nearly double the weight of female bison. These giant herbivores of the Great Plains once numbered in the millions (perhaps as many as 30 million) but were reduced to less than 500 individuals by the latter half of the 19th century.

Today, bison number in the hundreds of thousands, but most are restricted to isolated protected areas, production herds and private lands across a fraction of their former range in North America. A conservation success story, yes, but one that still needs an extra push if we hope to truly restore this species to the American West.

Putting your hands on a bison is a truly amazing experience. They are thickly covered in hair, with big heads and broad shoulders. Males have “beards” that sway from left to right as they move, noticeable even from a drone positioned hundreds of feet overhead. All this hair is great when you’re not wearing gloves (like me) and explains, in part, why they were so valued by indigenous peoples. Their pelts provided warmth amidst blustery winds and cold winters on the plains.

See if you can spot the male bison in this drone footage. Look for their “beards” that sway left to right as they move.

While seemingly gentle from a distance, bison are wild animals and can be aggressive and unpredictable when provoked. They deserve respect, with horns and hooves that can inflict damage. So, how do you put your hands on a bison without risking serious injury or death? And why would you choose to do so?

As part of an effort to better understand how bison move and use the landscape, our team at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute is studying collective movement behavior, or how groups make decisions and move together as a unit. This means that we need to fit animals with some sort of tracking device. Traditionally, we fit animals with GPS collars that are secured around the neck. However, this type of GPS collar is expensive, which means we can only track a small number of bison at once.

In January, the SCBI team (which included me, project lead and wildlife ecologist Bill McShea, and landscape ecologist and on-the-ground lead Hila Shamon) traveled to American Prairie Reserve in Montana to assist with fitting as many bison as possible with solar GPS ear tags. These inexpensive tags (less than $50 each) are developed by mOOvement, an Australian manufacturer. They weigh about 30 grams, or roughly the weight of a AA battery, allowing us to attach them to the animals’ ears. Initially developed to track the movements of cattle, American Prairie Reserve has expanded their use to bison. With any luck, the devices will collect the hourly position of each bison for the foreseeable future.

Upon arrival in Bozeman, Montana, we pushed off immediately to make the seven-hour drive to the Reserve. We arrived just in time for dinner (perfect!) and were greeted by American Prairie staff at the Enrico Education and Science Center on the Sun Prairie property. This would be the base of our activities over the next few days. Before heading to bed, we received a map of the work area and listened to a safety briefing led by American Prairie senior bison restoration manager, Scott Heidebrink, and reserve superintendent, Damien Austin, who would lead tagging/animal handling operations. The general message was “move slow to move fast.” The safety of the animals and of the people working with them was the number one priority. We would start the following morning at first light.

Prior to our arrival, the Reserve team had been working to round up as many bison as possible across the 26,000-acre management unit. They carefully herded bison toward an enclosure where they could be safely and efficiently handled. This low-stress facility was set up to hold and separate the bison into small groups so they could be individually handled, similar to how ranchers handle cattle.

American Prairie staff had the most dangerous task, physically stepping into the enclosure with the bison and using subtle, but intentional, body and arm movements to separate the animals into small groups. All the credit to them for doing so in a safe and professional manner, without any injury. Bison have the tendency to follow a leader, so we used this knowledge to coax them one by one through a chute. Mothers were kept with their offspring, and the bison were handled as quickly as possible to reduce stress throughout the process.

As bison reached the end of the chute, they would search for the light at the end of the tunnel (literally). Only one more obstacle remained in their way. Before exiting the chute, they had to pass through a machine called a hydraulic squeeze. The squeeze is a type of mechanical cage that first slows down the bison and then gently “squeezes” it to hold it still. Once a bison was secured in the hydraulic squeeze, we placed a halter over its head as an additional safety precaution and covered its eyes to help keep it calm. The halter further immobilized the head of each bison so that it could be safely handled by veterinary staff and personnel, including myself.

My job was quite simple. Quickly grab the ear, push back the hair and attach the solar GPS ear tag. Easier said than done on older, tougher animals, both because of their sheer strength and because their ears thicken with age. The bison were generally held in the squeeze for less than 10 minutes while tagging and disease testing were completed, with no injuries – a relief to all involved. After being handled, staff separated the bison into different corrals based on their sex and age.

All of the bison that would be staying on APR property received a solar ear tag and were immediately released after their tags were attached. Some bison, however, would be heading to new locations, such as the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation, to reduce grazing pressure on APR property and improve the genetic diversity of neighboring herds.

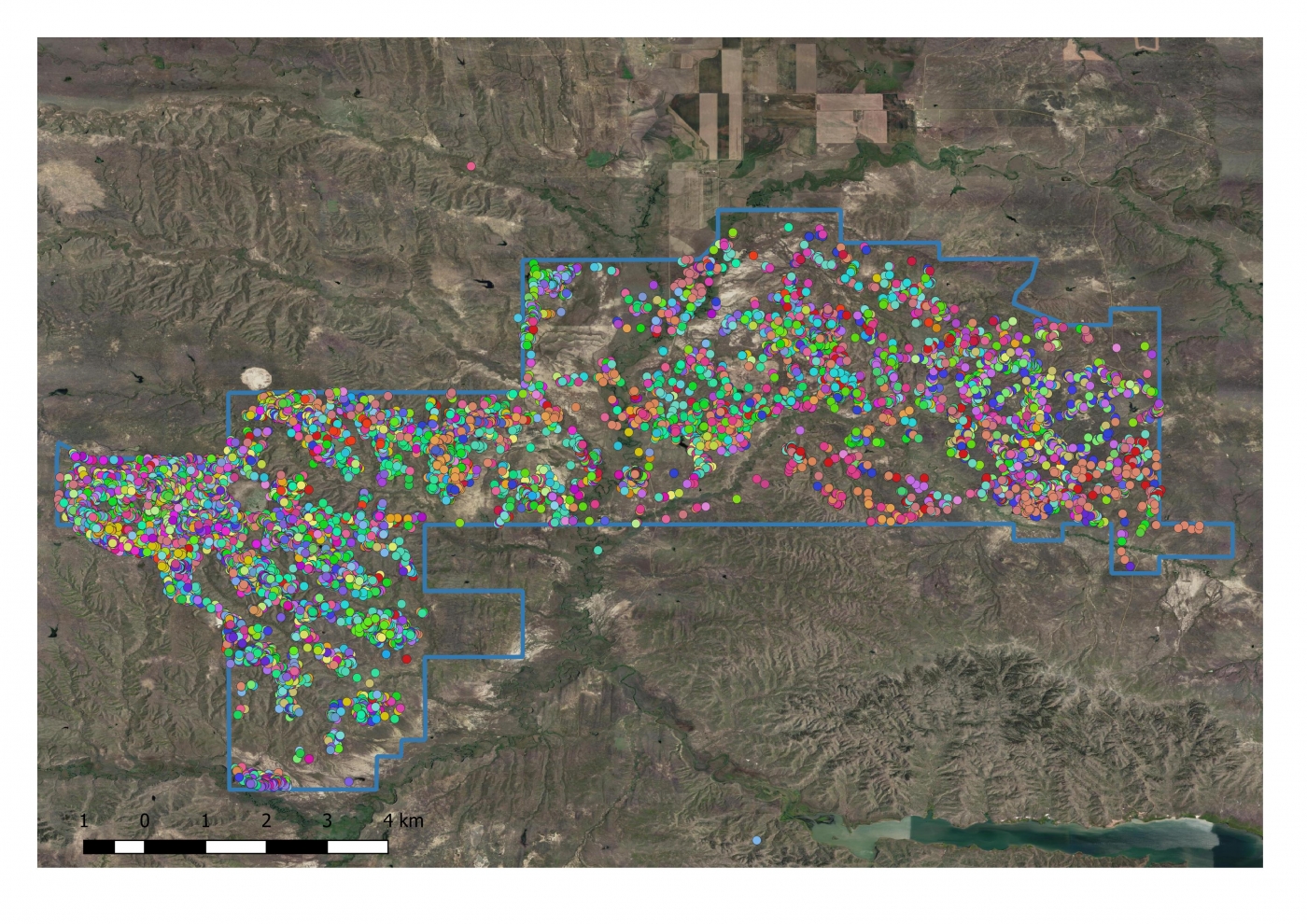

In four days, the team of 20-25 staff and volunteers handled 215 bison and fitted 89 of them with solar GPS ear tags. It was a remarkable achievement for all involved and will be the first study of this scale ever conducted on bison. While we are just starting to analyze the data provided by the ear tags, we are already seeing interesting results. Bison seem to use every inch of the 26,000-acre management unit. We are identifying the areas that they frequently revisit to determine whether some areas are more important to bison than others.

Over the next few years, we hope to use the data from this technology to provide a better understanding of group dynamics (what we call fission/fusion dynamics) and how these dynamics change throughout the seasons. We also want to know how bison make decisions, a core scientific objective of this research, so that we can better assess how animals are likely to move across the landscape.

Ultimately, we hope to provide a better understanding of the important role that these ecosystem engineers have on the environment and what has been lost in their absence – a central topic of Hila’s research and of particular interest to my own. One day, we simply hope to see these big, brown fantastic beasts roaming freely across the Great Plains, as they have done for thousands of years.

Related Species: