Focus on the Future: Alyssa Wetterau Kaganer

Focus on the Future is a series that seeks to highlight the early career scientists who conduct research at the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. Learn about undergraduate, graduate and post-doctoral fellows and the conservation research they are supporting through first-hand accounts and stories.

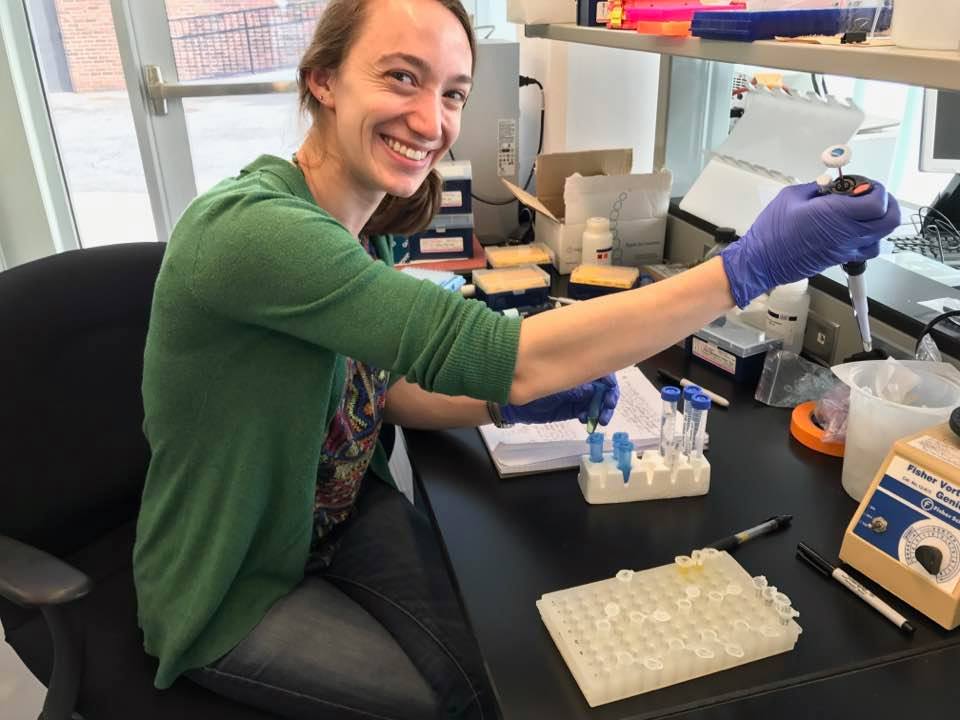

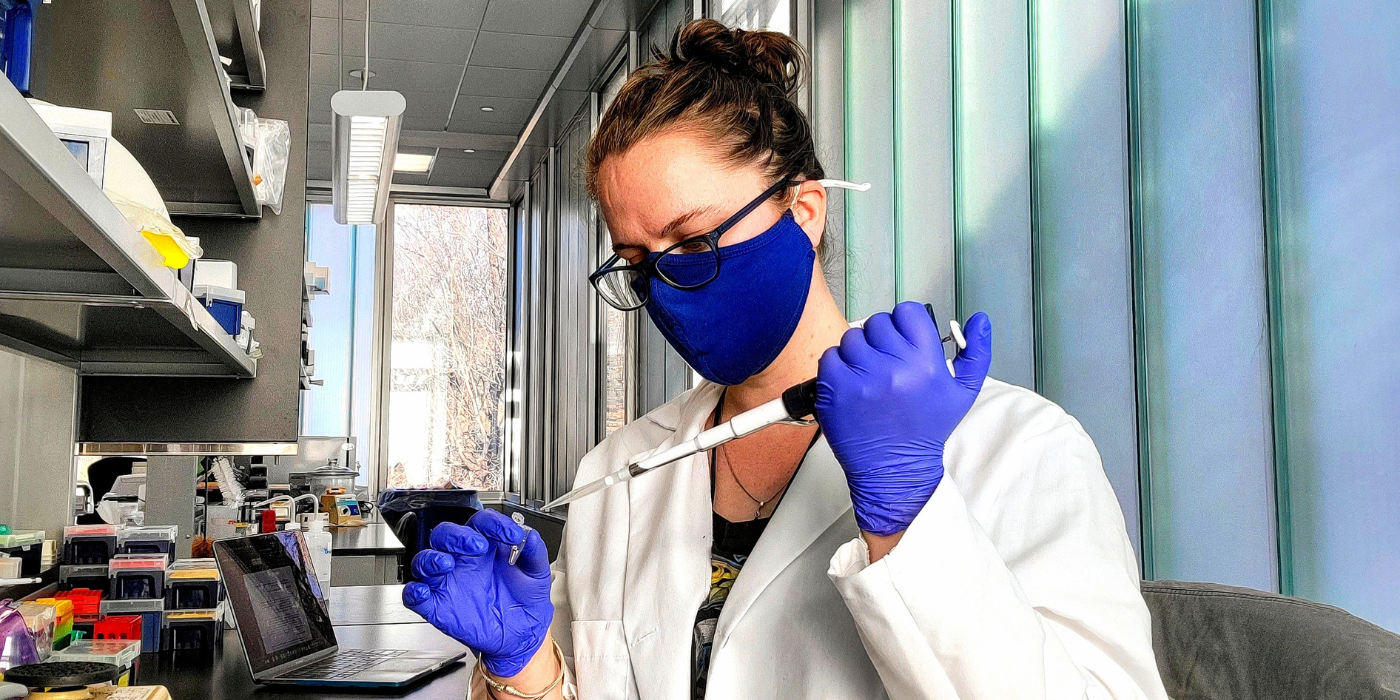

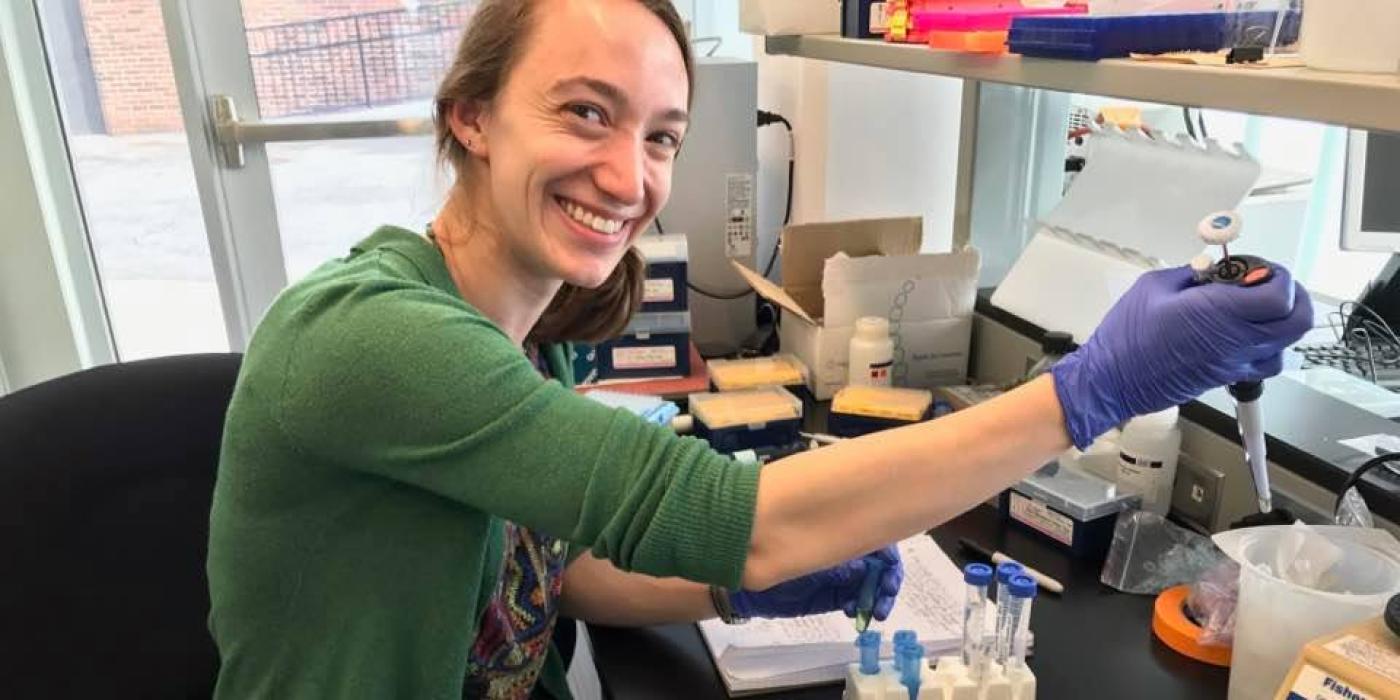

Featured photos courtesy of Alyssa Wetterau Kaganer.

Alyssa Wetterau Kaganer, PhD

Postdoctoral Associate at the Cornell Wildlife Health Lab

Former graduate fellow with the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute

I am from a small town outside of Albany, New York. I went to Cornell for undergrad, double majored in Biology and Animal Science and graduated with distinction in research in 2013.

As a small-town kid, I spent a lot of time outdoors. A lot of the hobbies my parents introduced me to were nature oriented. I originally planned to be a veterinarian and stumbled across the wildlife health lab at Cornell. I wound up snorkeling through some streams in Pennsylvania looking for hellbenders (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis) and was totally hooked. They are just a really cool species of salamander, the largest in America. They are genuinely enormous. I was really compelled by this idea of this unknown species as a canary in a coal mine, as far as water quality, and thinking about the ways we could be losing this important indicator species and people wouldn’t even know about it. When I got the chance to work on hellbender conservation as part of the Cornell-Smithsonian Joint Graduate Training Program, it seemed like a perfect fit.

Chytrid (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) is the leading disease threat to global amphibian biodiversity. It is found on every continent where amphibians are found, and it threatens hundreds of species. We know from past field work throughout the hellbenders’ range, they aren’t super susceptible to chytrid. But previously, chytrid-negative hellbenders were released into the wild and we saw extremely high rates of mortality in these animals due to chytrid. We wondered, ‘why is it these naïve animals released from captivity are so susceptible?’

We already know this disease depends on the activity of an amphibian, the fungus, and the bacteria that live on the amphibian’s skin, but we didn’t know specifically how that worked. There are many types of beneficial bacteria that live on amphibian skin and can produce an anti-fungal product, protecting the animal. We tried topical and oral methods of vaccination to try to mimic the way that wild hellbenders might be exposed to chytrid, whether from being in contaminated water or by eating prey that was contaminated, and looked at how the amphibian, fungus, and bacteria reacted. We used next-generation methods to study hellbender gene expression, and found hellbenders are launching an immune response in their skin to chytrid — both innate and adaptive immune responses. Which means the hellbenders immune systems are doing what they should and are keeping the animals alive. But that immune response wasn’t actually controlling the disease. Even when the fungus increased its disease-causing functions late in infections, we didn’t see any change in the disease state of the hellbenders. We also found that the hellbender skin bacteria didn’t have an effect on infections, they were just along for the ride.

This study is one of the first to look at multiple components of disease and immunity. There’s a lot of data and sifting through it logistically is quite challenging. But it’s giving us a holistic look at the immune function, which is valuable. Even though the vaccinations didn’t work the way we expected, it means there is something else protecting hellbenders in the wild from chytrid. But we also found immune priming through oral vaccination could potentially help other amphibian species that don’t mount a robust immune response to chytrid like hellbenders. This could help save other species in the long run.