Black-crowned Night Heron Expedition Blog

February Update

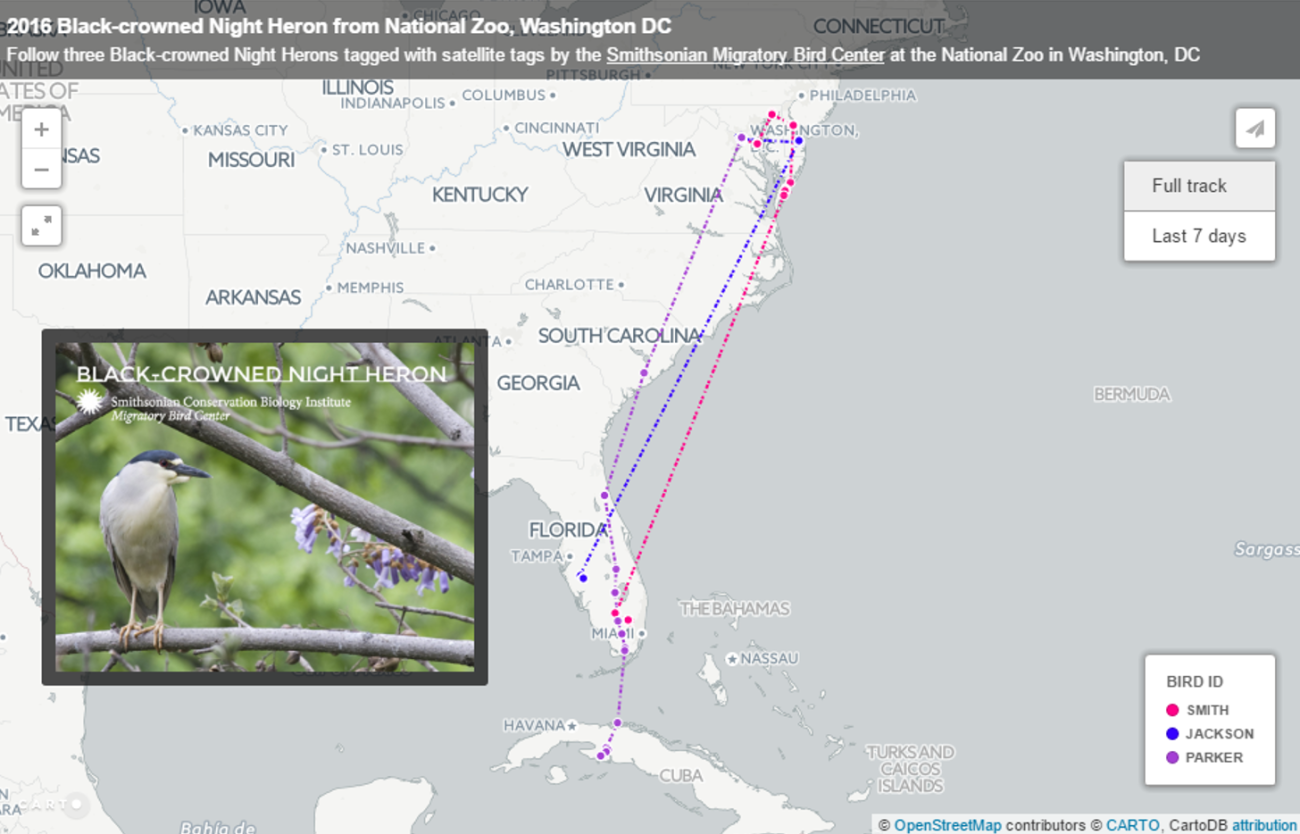

As part of the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center's continuing research of the black-crowned night herons that breed at the Smithsonian's National Zoo, we deployed satellite transmitters on three adult herons in June 2016.

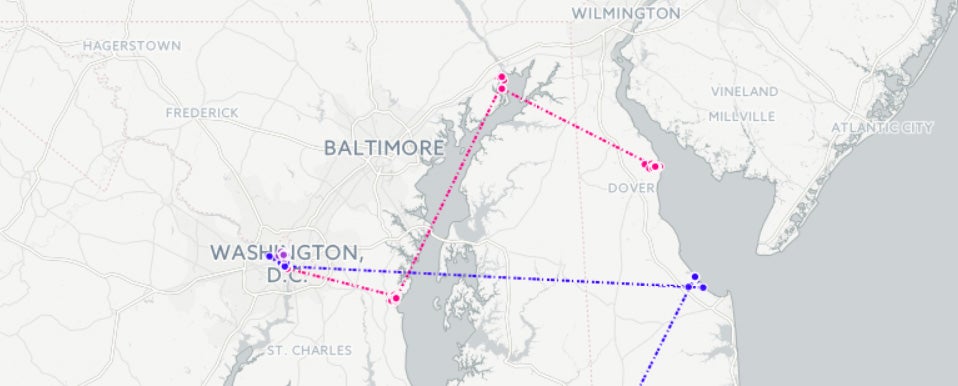

Jackson: This bird left the Washington, D.C., area in early August and headed east to the Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge in Delaware where it remained through early Sept. A few days later, on Sept. 6, the bird transmitted from just east of Sarasota, Florida. The bird was still at this location when the device last transmitted in early Dec. The battery is solar-powered, so the lack of sun may be preventing transmissions. As the bird begins its spring migration, we hope the battery will properly charge and begin transmitting locations again.

Smith: This bird left the Washington, D.C., area in early July and headed east to Herring Bay in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. After a few weeks, the bird headed to the northern most part of the Chesapeake Bay. A few weeks later, it flew east to the Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge in Delaware where it remained through late Sept. From late Sept. to late Oct. the bird stayed on the eastern shore of Virginia and then migrated south to the Everglades Wildlife Management Area in Florida. The bird is currently still at this location.

Parker: Our first Cuba bird! Parker remained near the Smithsonian's National Zoo until Sept. 10. After leaving, the bird's satellite tag transmitted from locations near Charleston, South Carolina, on Sept. 14 and Jacksonville, Florida, on Sept. 15. From there, the bird continued south through central Florida with the last location in Florida recorded on Sept. 22. Three hours later, a signal transmitted on the northern coast of Cuba! The last transmitted location for this bird is on Nov. 16 from the Zapata Peninsula, Cuba. This bird may be wintering in Zapata Swamp, in which case it is not unusual that no additional transmissions have been received. As with Jackson, the battery is solar-powered, so a lack of sun in the swampy habitat may be preventing new transmissions. As the bird begins its spring migration, we hope the battery will properly charge and begin transmitting locations again.

Over the last three years, we have color-banded 16 adult and seven juvenile herons and attached transmitters to 14 adult males and one adult female (nine satellite and six cell phone transmitters). This year's work was made possible by Conoco Phillips Global Signature Program, with additional support provided by Edgar Cullman and the Smithsonian Women's Committee. Thank you to all Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center staff who aided this effort, including Brandt Ryder, Emily Cohen, Tim Guida, Nora Diggs, Leah Culp and Autumn-Lynn Harrison.

This spring, we hope to see all of our tagged birds back at the Zoo. Over the last twelve years, the average arrival date is March 12.

Herons on the Move

This past June, for the fourth consecutive year, Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center scientists attached transmitters to three of the wild black-crowned night herons that nest at the Smithsonian's National Zoo's Bird House. This year, we attached a new transmitter for this study, a 9.5g (L 1.50" x W 0.68" x H 0.48") solar-powered satellite PTTs (platform terminal transmitter). Every 24 hours, the transmitter turns on and collects the location of the bird for 5 hours. The locations are transmitted to a satellite, then on to a receiving station where the data is processed. This process allows us to track the herons in near real-time.

One heron, Parker, is currently still local while the other two herons, Jackson and Smith, are in Delaware at the Prime Hook and Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge, respectively.

This year's work was made possible by Conoco Phillips Global Signature Program, with additional support provided by Edgar Cullman and the Smithsonian Women's Committee. Thank you to all Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center staff who aided this effort, including Brandt Ryder, Emily Cohen, Tim Guida, Nora Diggs, Leah Culp and Autumn-Lynn Harrison.

You can learn more about previous years in our Black-crowned Night Herons in D.C. expedition blog series below.

Fourth Time's a Charm?

For the fourth year, Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center scientists attached transmitters to three of the wild black-crowned night herons that nest at the Smithsonian's National Zoo's Bird House.

This year, we attached a new transmitter for this study, a 9.5g (L 1.50" x W 0.68" x H 0.48") solar-powered satellite PTTs (platform terminal transmitter). Every 48 hours, the transmitter turns on and collects the bird's location for 10 hours. The locations are transmitted to a satellite, then on to a receiving station where the data is processed. This process allows us to track the herons in almost real-time.

Herons: When Will They Return?

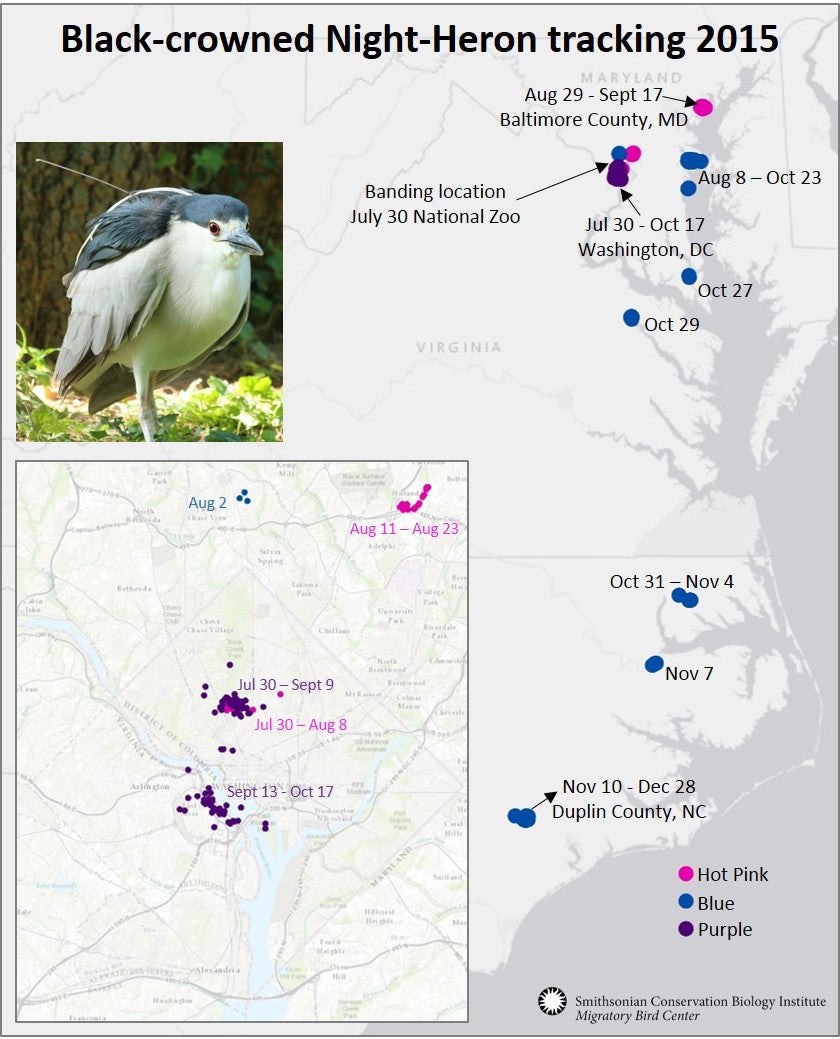

As part of the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center's continuing research of the black-crowned night herons that breed at the Smithsonian's National Zoo, we deployed satellite transmitters on three adult herons in July 2015.

Blue (female): After leaving the Smithsonian's National Zoo in early Aug., the bird remained near Annapolis, Maryland, for nearly three months. Finally, in the third week of Oct., it began its southbound migration, spending a week on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay and a couple weeks near Albemarle Sound, North Carolina. In early Nov., the bird arrived in Duplin County, North Carolina, approximately 75 kilometers (50 miles) north of Wilmington, North Carolina, in an area primarily composed of agricultural lands. The transmitter stopped transmitting Dec. 28 from this location. This bird spends the winter almost 600 kilometers (400 miles) from where it breeds at the Zoo.

Hot Pink (male): The bird remained in the area until late Aug. and then flew northeast about 100 kilometers (60 miles) near Middle River, Maryland. The bird was still at this location when the transmitter stopped transmitting in mid-Sept.

Purple (male): The bird remained near the Zoo until early Sept. From there, it flew south along Rock Creek across the Memorial Bridge to the Virginia side of the Potomac River near Arlington National Cemetery and Columbia Island. The bird was still at this location when the transmitter stopped transmitting in mid-Oct.

In addition to the transmitter, we put a metal band and a colored band around each heron's leg, so we can identify individual birds. Over the last three years, we have color-banded 16 adult and seven juvenile herons and attached transmitters to 11 adult males and one adult female (six satellite and six cell phone transmitters).

This spring, we hope to see all of our tagged birds back at the Zoo. Over the last twelve years, the average arrival date is March 12. When do you think they will arrive?

BC Night-Herons return to nest at @NationalZoo soon!

— Migratory Bird Ctr (@SMBC) February 10, 2016

Most arrive around March 12th

When will they arrive this year?

Thank you to supporters of the heron research including, the Smithsonian Women's Committee, Edgar Cullman, Helen DuBois, Clive Runnells and more.

Zoo Heron December Update

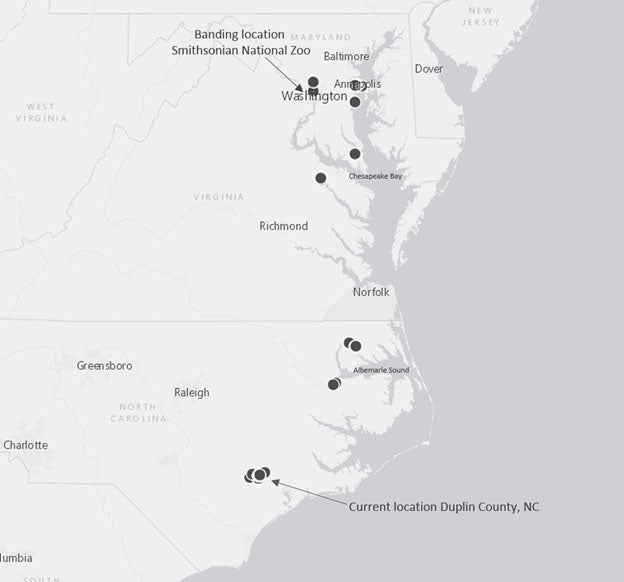

Of the three black-crowned night herons tagged with satellite transmitters this summer at the Zoo, only one tag is still transmitting.

After leaving the zoo in early Aug., the bird remained near Annapolis, MD for close to three months. Finally, in the third week of Oct., it began its southbound migration, spending a week on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay and a couple weeks near Albemarle Sound, North Carolina.

In early Nov., the bird arrived in Duplin County, North Carolina, approximately 75 kilometers (50 miles) north of Wilmington, North Carolina, in an area primarily composed of agricultural lands.

Zoo Heron Update

As part of the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center's continuing research of the black-crowned night herons that breed at the Smithsonian's National Zoo, satellite transmitters were deployed to three adult herons in July 2015. The battery on the transmitters should last about one year giving us information for both spring and fall migration and where they spend the winter.

Our work with the herons first started in 2013 with satellite transmitters on three herons and continued last year with solar-powered cell phone transmitters on six herons. Over the last three years, we have color-banded 16 adult and secen juvenile herons and attached transmitters to 11 adult males and one adult female (six satellite and six cell phone).

Thank you to supporters of the heron research including, the Smithsonian Women's Committee, Edgar Cullman, Helen DuBois, Clive Runnell and Ashley Taylor Bronczek.

Can You Hear Me Now?

At the Smithsonian's Migratory Bird Center we are pushing the edge of animal tracking technology to understand and conserve migratory birds. With an explosion of new technology in the last few years, you might think it's possible to track anything anywhere, but the truth is that we still have a long way to go.

The biggest challenge is in reducing the size of transmitters while increasing the accuracy of locations. Often, the trade off is between the weight of the transmitter versus the battery life, accuracy and number of locations, and how the researcher receives the data.

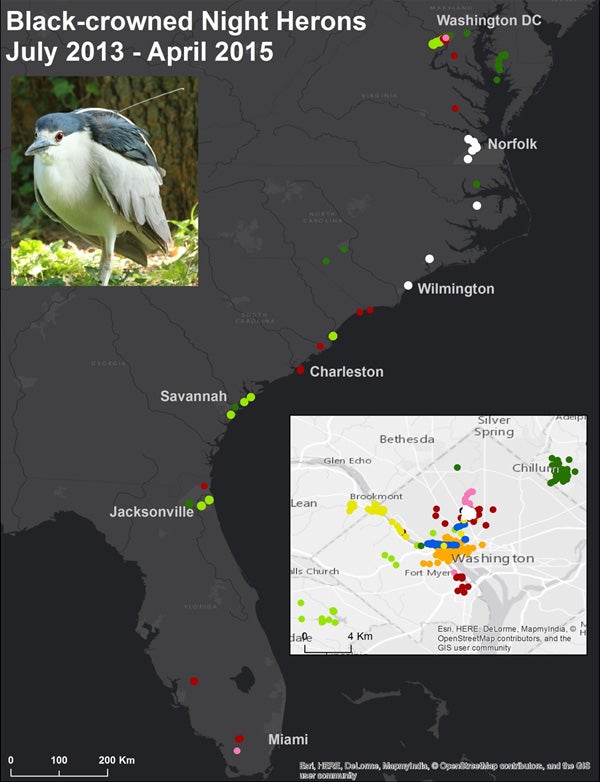

Our project tracking the black-crowned night herons that roost every year by the Bird House at the Smithsonian's National Zoo is an example of how we are pushing the limits of new tracking technology. In 2014, the manufacturer, Cellular Tracking Technologies, and SMBC put solar-powered GPS-GSM (Global System for Mobile Communications) or cell phone transmitters on black-crowned night herons for the first time.

The cell phone transmitters collect a GPS location of the bird every hour and transmit locations via the cellular network every few days. Herons are most active at dawn and dusk, so it was a mystery to see if the solar-powered battery would remain at high enough levels to collect and transmit heron locations. Additionally, issues with the coverage of the cellular network or weak signals (can you hear me now?) in some areas can prevent the data from being transmitted.

Overall, we had mixed results with the cell phone transmitters:

Pink: This bird flew greater than 1,000 miles to spend the winter in Everglades National Park, Florida! It returned to the Zoo this spring, and the last transmission was from the Zoo in April 2015.

White: We received points from the same location near Wilmington, North Carolina from early Dec. 2014 through March 2015 when the transmitter stopped transmitting. The heron may have died or the transmitter may have fallen off and kept transmitting from the same location. A colleague went to the location to look for the bird or transmitter with no luck. Hopefully, we will see the bird at the Zoo this year.

Dark Green: This bird migrated to a neighborhood lake in Jacksonville, Florida. The bird could have stopped here during migration or spent the entire winter here. The transmitter stopped transmitting early Nov. 2014 after four months.

Blue: We received many local locations from this bird along Rock Creek down to the Georgetown waterfront. The bird was last located Aug. 2014 along the Potomac River/Capital Crescent Trail in Foundry Branch Valley Park (after one month of data).

Yellow: The transmitter stopped transmitting after a few weeks with most of the points on the Zoo grounds. This bird was sighted this spring at the Zoo with the transmitter still attached.

One transmitter did not work at all.

Over the last two years, we color-banded 13 adult and four juvenile herons and attached transmitters to nine adult males (three satellite and six cell phone). This July, we plan to deploy three versions of a new and improved satellite transmitter used in 2013.

Thank you to the Smithsonian Women's Committee and Edgar Cullman, Helen DuBois and Clive Runnells who continue to support the heron research and many other projects at SMBC.

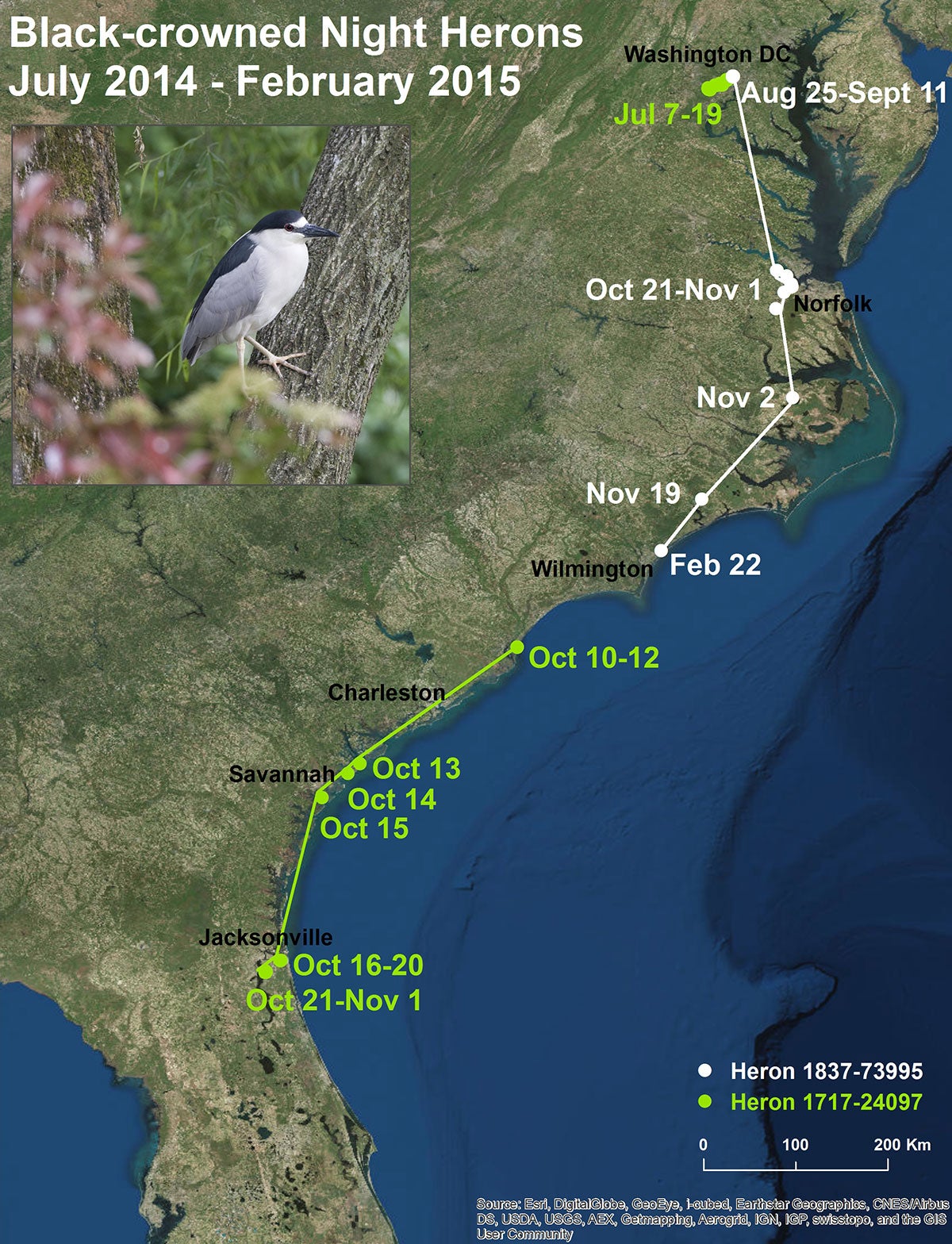

Night Heron Update

July 2014 began our second season of tracking the fall migration of black-crowned night herons that breed at the Bird House.

See the journey of two herons, who were fitted with solar-tracking devices, thanks in part to support from Smithsonian Women's Committee.

Tagging Black-crowned Night Herons

Every spring and summer, the Smithsonian's National Zoo's Bird House hosts some very special migratory guests — about 100 black-crowned night herons.

For the past century, the birds have arrived at the Bird House — their only rookery in Washington D.C. — every April. Yet, where the birds go after they leave in Aug. or Sept. remains a mystery. For the past century, the birds have arrived in April and departed between Aug. and Sept., but scientists did not know where their southern destinations were or what challenges they faced to reach them.

Last summer, Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center scientists attached tracking devices to four birds, gaining the first glimpse into the birds' migration south. A couple birds had made it to Florida before the transmitter batteries died.

This July, scientists outfitted six birds with more advanced tracking devices, thanks to support from the Smithsonian Women's Committee. The light-weight, solar-powered trackers use cell phone technology to transmit location data every two hours. This more precise system allows scientists to track the birds in near real-time and gather clues about what challenges they face on their marathon journeys.

The backpack-like transmitters do not harm the birds and are custom fit to each individual. Zoo visitors can see the six herons with the trackers flying around the Bird House.

Black-crowned Night Heron Study

Every spring, approximately 100 breeding pairs of black-crowned night herons arrive at the Smithsonian's National Zoo in Washington, D.C. The herons have been nesting here since before the Zoo was established in 1889, yet we still do not know where they spend the winter.

Last Aug., the Smithsonian's Migratory Bird Center and the Bird House began a pilot study to unravel this mystery. Three adult herons from the rookery were fitted with satellite transmitters. The satellite transmitters emit signals for 2 hours, daily during migratory periods and every other day during the remaining months.

Signals from the transmitters are picked up by satellites passing overhead and relayed to processing centers where the data is collected and processed to provide the coordinates of the bird's location.

Meanwhile, it remains to be seen whether the current locations of these birds are temporary stops or final destinations. One thing is certain, we know more now than we did last summer!

- JoGayle (in green) left the breeding site on Aug. 13 but remained in the Washington, D.C., area near the Georgetown waterfront. Unfortunately, as of Dec. 22, for unknown reasons, the transmitter stopped receiving locations.

- Russ (in red) left the breeding site on Sept. 22. Over the next six days, it made its way to Charlotte County, Florida, a distance of 1,400 kilometers. It remained there until Dec. 30, after which it traveled another 150 kilometers to the Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport. This transmitter also stopped receiving locations as of Jan. 14, 2014.

- Clive (in blue) left the breeding site on Aug. 15 but remained in the Washington, D.C., area for another two months. On Oct. 16, it started to move, first going to the eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay and staying for about three weeks, then heading south on Nov. 6. It has been in northern Florida, 20 kilometers southwest of Jacksonville, Florida, since Nov. 20. For unknown reasons, this transmitter also stopped receiving locations as of Dec. 22.

Related Species: