Winter Ecology in Jamaica Expedition Blog

It has been a busy field season tracking the ecology of migratory birds down here at the long-term study site at the Font Hill Nature Preserve in southwest Jamaica. This year, we’ve been working on projects that include assessing how wintering bird populations change through time, the consequences of climate-induced drying in the Caribbean on bird behavior and the ways in which birds may (or may not) be adapting to cope to those changes. Although we primarily focus on the winter ecology of these migrants, we can’t help but also track how events on the wintering grounds carry over to influence migration and, ultimately, breeding. Coupling new technology with proven and reliable field techniques, we are getting a better overall sense of the ecology of migratory birds across the full annual cycle and the potential factors that might threaten their populations. With the expected departure of our birds coming up in the next couple of days, now is as good a time as any to highlight some of the work we’re doing.

Long-term Research in Environmental Biology (LTREB)

This year, the 2017 LTREB crew have spent the season banding migratory and resident birds, territory mapping American redstarts and conducting vegetation surveys in logwood and mangrove habitats at Font Hill.

The season involved two eight-day periods of intensive mist-netting and banding of land birds in our logwood and mangrove plots. Over the course of the two periods, we captured and banded a total of 529 individuals! This was a great opportunity to get our hands on some very cool migratory and resident Jamaican birds.

Most of our season was devoted to territory mapping our focal species: the American redstart. With the changing weather patterns across the season (from drought-like conditions to heavy and consistent rain events) many of our banded birds seemed to change or leave their known territories. This added to the challenge of mapping these birds and kept the LTREB crew constantly on their toes!

Now, as spring migration gets underway, the LTREB crew has turned their focus to capturing departure dates for all of the redstarts mapped this season. This involves returning to approximately 100 redstart territories every day and trying to detect the bird. Once we no longer consistently find the bird, we can assume it has departed and is on its way north for the breeding season.

Get a Move on with American Redstarts and Swainson’s Warblers

By the time birds arrive in early fall, much of the Caribbean begins to slowly come out of a wet season and progressively dry. This means migrants that call the Caribbean home for the winter must endure the driest conditions of the year.

This year, our work is centered around understanding how birds utilize habitat throughout the winter when conditions go from wet to dry and food availability (insects!) declines. We have tagged close to 45 American redstarts during three periods (early, mid and late) that correspond to a gradient of wet to dry conditions.

Once a bird is tagged, we spend the following 20 to 30 days tracking their movements, seeing where they go during the day and where they roost at night. For the most part, about 50 percent of the birds spend nearly all of their time in an area no bigger than one-quarter of an acre (75 square feet). Day in and day out, these birds predictably roam throughout their territory foraging for any insects they can find. All the while, they stay on the lookout for any intruders that might come to steal their food.

The other 50 percent of the birds do something completely different. Instead of defending a territory and remaining settled, these birds roam across the study sites. They go from spot to spot, quickly and sneakily foraging and moving on.

Until recently, these individuals were impossible to track. Consequently, we don’t know too much about why these birds seem to roam around. With these radio transmitters, we are gaining insights into this behavior, its prevalence and the consequences (if any) that this movement strategy has on these birds. Stay tuned as we dive into their mysterious lives!

To study a cryptic migratory bird species, like the Swainson's warbler, one must have (but not be limited to) three attributes: serious patience, hardcore stamina and undying dedication. Oh, and if you are trying to recapture said species, I would recommend head-to-toe camouflage.

Many birders and biologists alike hunt long and hard to spot an elusive Swainson’s warbler, hopping stealthily through bottomland hardwood and rhododendron thickets in the southeastern U.S. Before I began my master’s degree research studying the winter ecology of Swainson’s here at Font Hill, this is the extent of what I knew about the species.

The bird’s elusive nature also means limited research has been conducted, especially on their wintering grounds. Only a few key studies in Jamaica have determined some ecological aspects like winter habitat use and prey consumption. I am super excited and, to be honest, quite honored to be researching Swainson’s warblers. The goal of my research is to determine the adaptive capacity of a migratory songbird to respond to worsening drought conditions attributed to the drying trend occurring in the Caribbean. But by focusing on Swainson's warblers, as I pursue this question, I am also learning a ton of vital ecological information about the species, which I think is pretty special.

With this being my second field season, I knew what to expect as far as what capturing methods to pursue and how much effort would be needed to catch and track these birds all season long. However, although I have experience in the art of catching Swainson’s warblers, that does not make it easy!

The abundance of Swainson’s warblers present in Font Hill is less than other migratory species we see, such as ovenbirds or black-and-white warblers. Their home ranges are also quite large, so detecting individuals can be tough. I typically systematically search for new individuals using playback of their songs/calls. Once captured, I equipped each individual with a radio transmitter to follow their movements for the duration of the season. With every new location point taken, more information was gained about the species habitat utilization.

Vegetation measurements, soil moisture, arthropod composition and abundance were all determined for each individual throughout the season, which helps us understand shifting home ranges and differing seasonal movements. With help from technician Natasha Barlow, I have obtained an immense amount of data on wintering Swainson’s warblers, and my second field season has been a complete success.

It seems that as quickly as the field season takes off, it comes to an end. Swainson’s warblers began their journey north during the last week of March, with many of our focal individuals already migrating by April 5. Although there are no more birds to track, the season is far from over. There are countless hours of vegetation measurements to take and leaf litter samples to sort.

Excitingly, I have equipped a handful of Swainson’s warblers with nano-tags that can be detected on radio towers throughout their migration. So, even though they have departed Jamaica, we should be able to get a sense of their migration timing and locations during their trip north. We have also obtained specific departure dates and times for these individuals, thanks to Bryant’s radio tower array here at Font Hill. Hopefully, the data keep rolling in!

I am humbled and grateful to work alongside brilliant minds and contribute so much knowledge about a species of conservation concern. Swainson’s warblers make your jaw drop in the rare moments that you observe their behavior. How swiftly and aggressively they forage. I gain more respect for them every time I detect a strong radio signal transmitting right in front of me, yet never spot the bird. Swainson's are so good at what they do. They really live up to their elusive reputation, and they sure had me running around non-stop over these past two years! It really has been an unforgettable journey.

An Ornithological First

For the first time, researchers from the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center and graduate student Bryant Dossman, from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, deployed geolocators on American redstarts in Jamaica to determine where these birds go to breed. Weighing just 6 to 7 grams, redstarts are the smallest bird yet to carry a tracking device. We now wait until next Jan. to recapture the birds and find out their secrets.

And the Countdown Begins

Over the past several years, crews have been coming down to Jamaica to collect valuable data on several migratory songbirds including the American redstart and this year has been no different. It's been a busy season and our crews of intrepid explorers have worked hard to track American redstarts, ovenbirds, and Swainson's warblers. But as folks in the United States begin seeing their first signs of spring and perhaps of few of the early returning migrants, we are getting ready to say goodbye to the birds we've been studying these past few months.

Over the coming weeks, most, if not all, of our migrants will have departed and begun their journey north to their breeding grounds throughout the United States. As one of the least studied portions of the annual cycle and yet the most perilous—our ability to conserve migratory bird populations hinges on not only our understanding of how birds use their wintering grounds but also on how they make their way back north during migration.

However, this season, our efforts in Jamaica will not end when these birds depart. By using new tracking technology, we will be able to follow these birds as they head north across the Caribbean and into the United States.

Where do these birds go? How long do they take? What routes do these birds follow? These questions and many more will begin to be answered as we take the next step in furthering our understanding of the ecology of migratory birds.

American Redstarts

Long Term Research and Environmental Biology (LTREB)

With spring approaching, the field season here in the tropics nears its end as migrant birds start gearing up to depart Jamaica for their breeding grounds in North America. Over the past few months members of the Long Term Research and Environmental Biology (LTREB) project have been mapping habitat use and territoriality of American redstarts in both logwood and mangrove habitats.

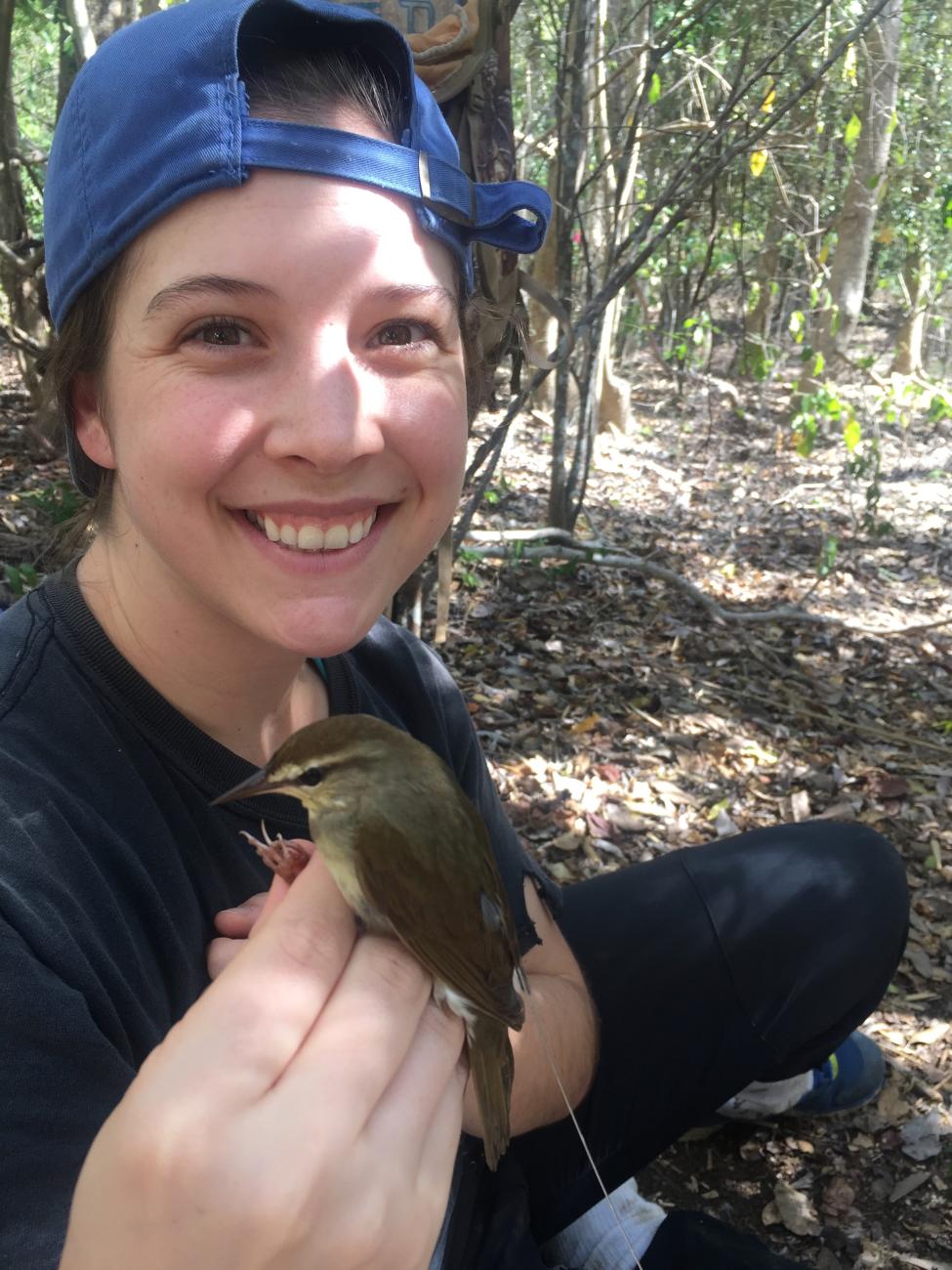

Boo Processing a newly captured redstart!

This adult male redstart is just lounging in the net waiting for someone to carefully remove him. Over the entire season, we will catch more than 500 birds just like this!

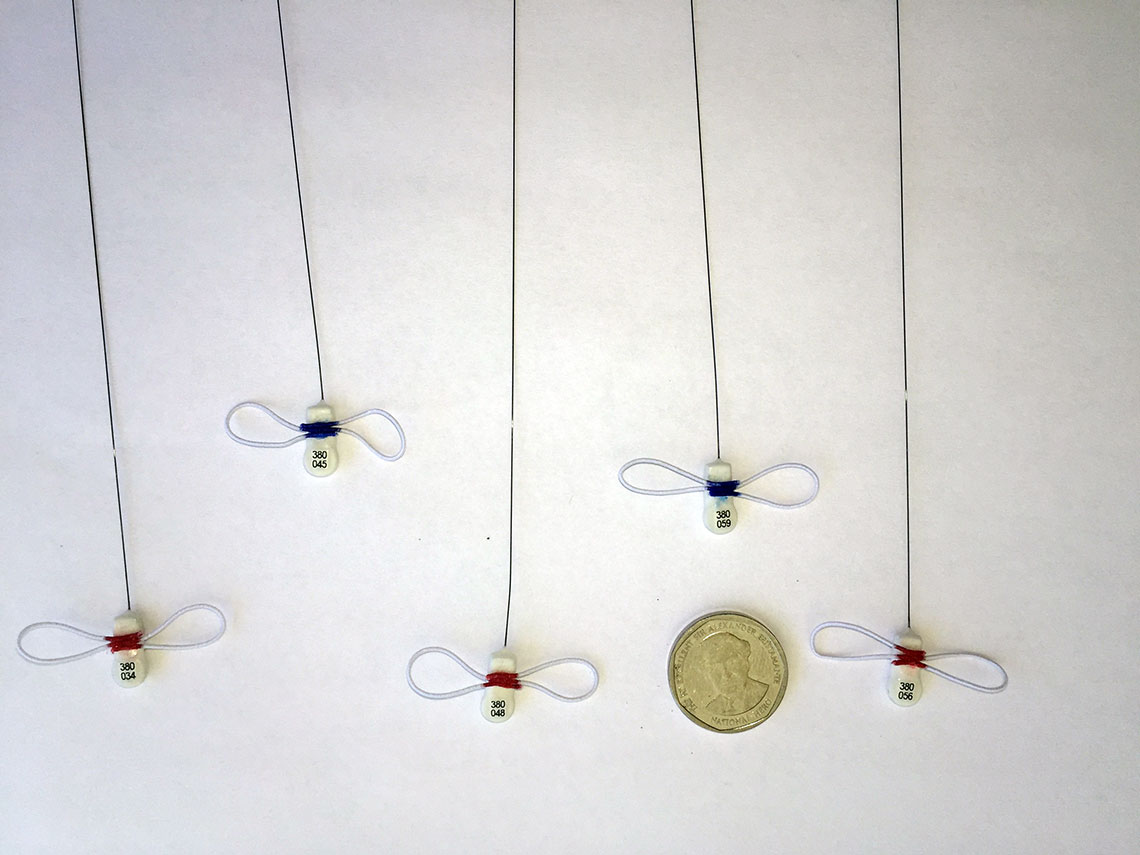

A few radio transmitters all prepared and ready to be placed on some redstarts! The coin in the picture is dime sized…these tags are tiny!!

In addition, re-sight efforts, where known, color-banded individuals are searched for on a regular basis, were established to analyze detection probability of these redstarts within their territories at Font Hill Nature Preserve. These re-sight surveys also provide data that can be useful to determine site fidelity and potentially overwinter survival of this species. This re-sight data can also show changes in redstart habitat use in relation to changing climate variables, such as amount of rainfall.

Currently, the crew is in the process of re-catching redstarts that were banded in the beginning of the season and re-taking body condition measurements, such as weight and fat levels, during this late-winter period. With this we seek to learn how habitat quality and insect abundance influences the conditions of these birds over the winter. Our crew has also begun the task of monitoring birds prior to spring departure. By searching territories every day for known birds, we can determine when birds depart for their breeding grounds in the next coming weeks!

Movement Ecology

How large of an area do redstarts use and how much do they move around during the winter? Till now, our understanding of this has been determined by going out, each and every morning, finding a bird and mapping it for a little while before moving on to the next bird (see above). After a while (or a whole season) these efforts eventually begin painting a picture of where a bird usually lives (eats and sleeps) throughout its time on the wintering grounds.

Video of our researchers in Jamaica releasing a recently radio tagged American Redstart! #ornithology #tech4wildlife pic.twitter.com/pyq8AcuNxb

— Migratory Bird Ctr (@SMBC) April 6, 2016

Despite these impressive efforts our efforts only capture a small portion of the secretive lives these birds live. With the help of radio transmitters, we are starting to gain a peek at what these birds do throughout the day, especially when we fail to find them. Just from our efforts these past weeks we are starting to see that these birds do a lot more than what we initially thought, sometimes traveling more than 1.5 km away from their "home" exploring other parts of the study sites.

Our job this season has been to dive specifically into this behavior and to gain an understanding of why birds leave their territories and why are certain birds more prone to this behavior than others. Stay tuned for the next edition of Keeping up With the Redstarts.

Swainson's Warblers

The time has come for the wintering Swainson's warblers to depart on their journey North. Within the past few days we have seen several birds disappear from the plots, which isn't surprising after recently capturing some extremely fat individuals. Even so, it is still hard to believe the season is quickly coming to an end.

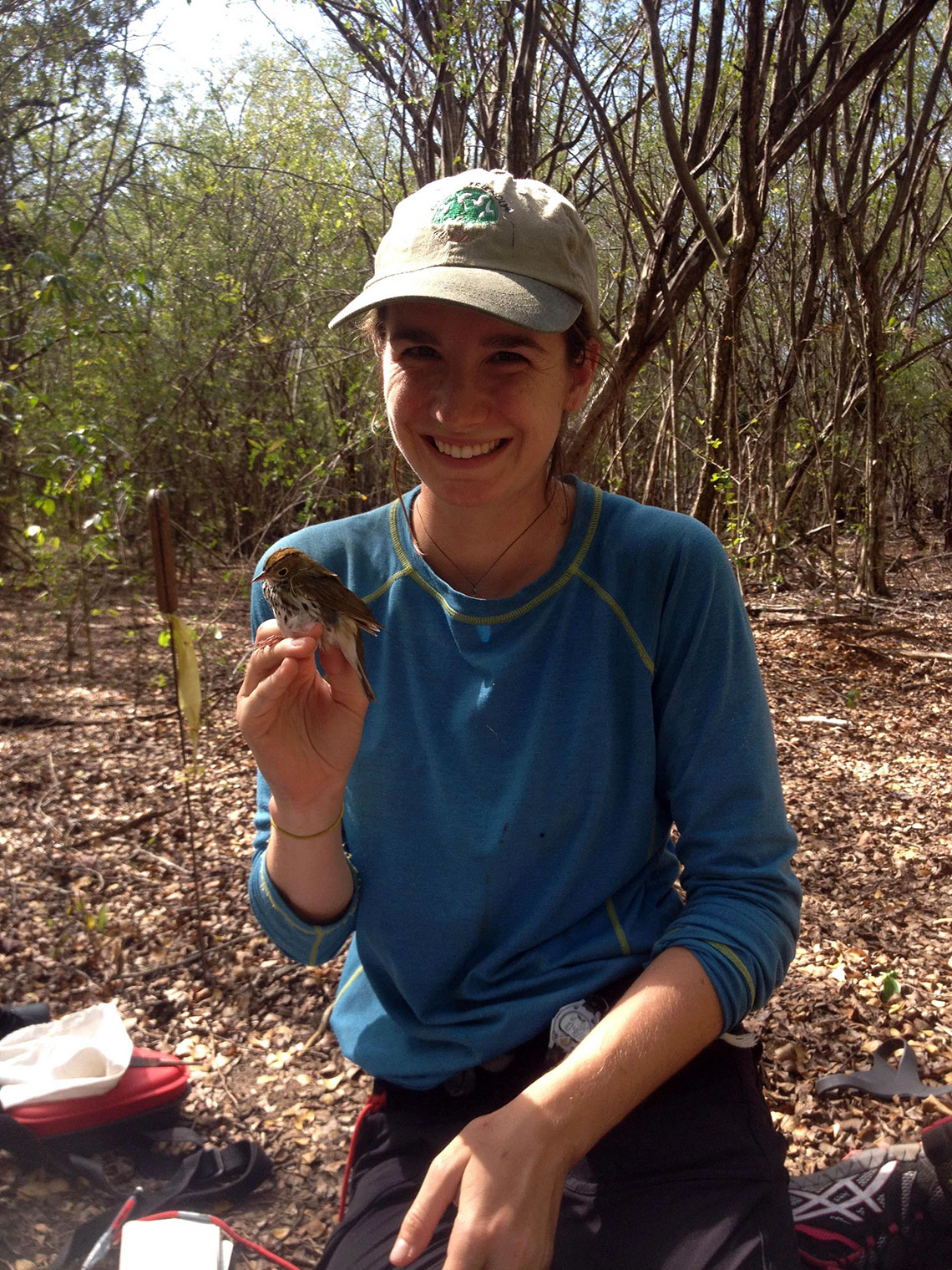

Cody and Alicia celebrate the re-capture of another elusive Swainson's Warbler. You can barely make out the antenna coming off the back of the bird!

Over the past month we have been finishing up the hand tracking of our radio transmittered Swainson's to complete each birds' late season home range. More habitat data will be collected including what leaf litter arthropods are available in each different habitat and each bird's home range. Not only are arthropods collected, but we target geckos as well.

Alicia Brunner using radio telemetry to find her radio tagged Swainson's Warblers!

An interesting thing about Swainson's Warblers is that they eat lizards, and with a bill like that you can see how! I have learned a lot about these mysterious warblers and continuing to learn more every day. For those reading from the Southeastern United States, keep a lookout for incoming Swainson's Warblers; they are tricky to see but when you finally come across these fantastic birds, it is worth every minute!

Ovenbird

Team Ovenbird is running in high gear as we prepare for the bird's departures back north within the next 15 to 20 days! Over the past 6 weeks, we (technicians Robyn Bath-Rosenfeld and Adrienne Dale) have been continuing to track the radio-tagged ovenbirds in order to determine their home ranges. Within these home ranges, 20 random points have been selected to conduct arthropod counts.

Group photo time! Adrienne Dale, Robyn Bath-Rosenfeld, Justin Saunders, and Alicia Brunner (Left to Right).

At each point we record all arthropods (ants, spiders, termites etc.) that come through the plot in order to assess the amount of food available to ovenbirds and their ground-foraging ways! We continue to track the birds on a daily basis and watch how their home ranges change as they prepare for migration!

A color banded Ovenbird.

Sometimes we try to bring everything with us into the field! Adrienne Dale

Adrienne with a newly captured Ovenbird.

Within the next two weeks we will attempt to re-catch all of our birds that have been tracked since February and replace their radios with yet another form of tracking technology, Lotek's geolocators (geos). The birds will carry these geos to their breeding grounds for the summer, recording their migration pattern as they fly north! Our hope is to recapture these individuals in their same home ranges next winter! Yay for the amazing site fidelity of these migratory passerines!

Studying Warblers in Jamaica

This season marks 26+ years in Jamaica studying the winter ecology of many of our North American warblers! This year in particular, we have a dedicated crew of volunteers and leaders collectively working on three species: the American redstart (the long-term focal species here in Jamaica), ovenbirds, and Swainson's warblers.

By using a combination of intensive banding and re-sighting with VHF radio telemetry we seek to uncover many unique and interesting facets of how these species survive the winter during the Caribbean dry season and prepare for their Spring migrations back to the United States and Canada! But life in Jamaica doing fieldwork isn't always sunshine and white sand beaches, its BETTER!

In between battling mosquitos and rogue cattle, we will collectively see more than 100 different species of birds including many of Jamaica's endemics. But before I go to far into the details, Ill let each crew give their take on life as a field biologist in Jamaica.

American Redstarts

ASY male American redstart. Photo by Bryant Dossman.

ASY female American redstart with radio transmitter. Try to find the antenna coming off it's back. Photo by Justin Saunders.

Long Term Research and Environmental Biology (LTREB)

We are once again conducting research on migratory bird species that travel to Jamaica for the winter months. This January at Font Hill Nature Preserve, in St. Elizabeth, Jamaica, LTREB field work consisted of banding efforts focused on catching both wintering migrants and endemic Jamaican birds, along with conducting vegetation and invertebrate surveys, but has now shifted to focus primarily on Redstarts, or "Christmas Birds" as they are called locally.

As the season progresses, our crew of 4 are continually working to capture American Redstarts and map their use of both logwood and mangrove habitat types over the winter period. We use varying tactics to target these birds, including using playback calls in the field to lure birds into our nets. Once a redstart is caught, it is carefully extracted and brought to the banding station for ageing, sexing, measurements and banding. At this point, each bird is given a unique color band combination, so individuals can be identified in the field.

We then strive to follow each color-banded individual multiple times over the mid-winter period to best estimate its territory location and size. Currently, we are mapping close to 200 banded redstarts on 2 logwood plots and 3 mangrove plots. By the conclusion of the season, our goal is to have complete maps of these birds and their overwintering use of habitats at Font Hill.

Justin Saunders actively tracking a redstart that was recently tagged. Look how happy he is!

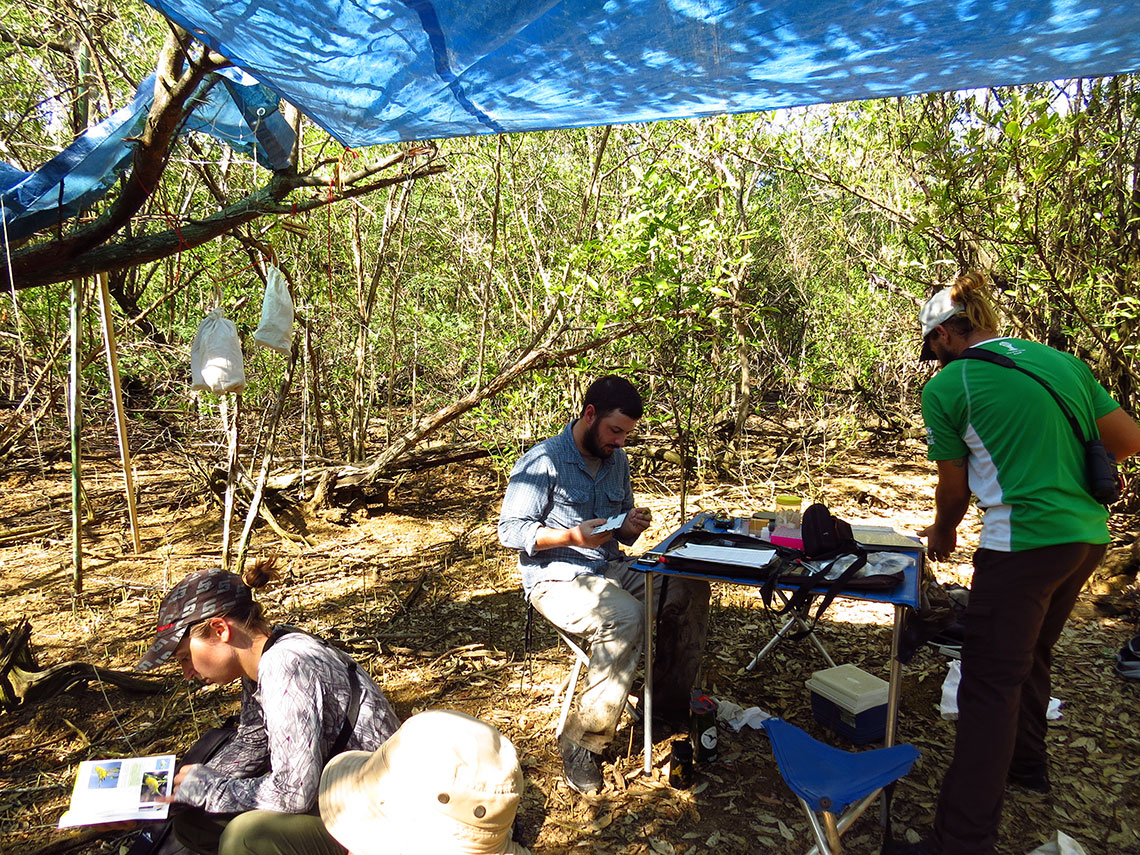

The LTREB crew actively banding. Photo by Boo Curry.

This redstart received 2 color bands and 1 USGS aluminum band. Photo by Boo Curry.

Movement Ecology

In addition to the ongoing long-term research on American redstarts, this year we are embarking on a project investigating the behavior and movement ecology of this well known species. For the first time, Justin Saunders (Volunteer) and myself (Bryant Dossman, PhD student) will be attaching miniature digitally coded VHF radio tags (Lotek Wireless) to American redstarts on the wintering grounds. By using an automated telemetry array designed to track these birds continuously, we aim to uncover a wealth of information on how birds use space and habitat during the dry season but also the migratory routes they take once they depart north from Jamaica, through Florida, and likely up the east coast.

Given their light weight design, these tags weigh less than 5% of their body weight. Eventually, after the birds have left Jamaica, these radio transmitters will fall off by design, ensuring that we get the data we need from these individuals but also ensuring that we don't overburden them. These tiny devices will give us a bird's eye view of life during the winter and migration and help inform conservation of not just redstarts but all of migratory passerines. See some of the pictures below to see how small these radio tags are!

Swainson's Warblers

I have to say—studying one of the most elusive bird species in North America, the Swainson's warbler, for the past two months sure has its fair share of challenges, but discovering more and more about the winter ecology of these secretive birds every day is a fantastic reward. I'm Alicia Brunner, a Masters student working with Dr. Chris Tonra at The Ohio State University and I will be chasing Swainson's around in Jamaica for the next two years to try and understand how these individuals use their winter habitat.

Radio transmitters are attached to each bird caught and thereafter we track their movements almost daily. My goal is to determine if these birds have the ability to track moisture and prey abundance throughout their time spent in the Caribbean. This question is important because although a lot is known about American redstarts in Jamaica, as a ground foraging species, the Swainson's Warbler relies on very different strategies to find insects, so they may be affected by fluctuations in moisture in ways unlike those of a canopy foraging warbler. There is much to be learned about the behaviors of Swainson's Warblers during the nonbreeding season and we are working hard to answer many of these uncertainties!

Find the field tech? Cody Lane dives head first into some prickly ping wing to gather valuable habitat data! Photo by Alicia Brunner.

Alicia Brunner and her advisor Chris Tonra (Ohio State University) celebrate another successful day catching the elusive Swainson's warbler.

Currently, the Swainson's crew, which includes me and my excellent field technician Cody Lane, are tracking individuals and have been seeing some interesting movements. The birds use a gradient of moisture from the wet swampy mangroves all the way to the dry cracking Logwood forest and we are now determining the size and variation of each individuals home range. Lately we have been gathering a lot of vegetation data to characterize what type of habitats are most dominant in each birds home range.

We have been taking measurements such as leaf litter composition and and shrub density, and acquiring pounds and pounds of leaf litter samples for arthropod collection. Let's just say we will be spending a good amount of the next week or so in the lab searching for insects! Thanks for your interest and I hope to be writing more frequent updates in the coming weeks.

Ovenbirds

Team Ovenbird, led by Mer Mietzelfeld from the University of Maryland Baltimore College, and her tech Robyn Bath-Rosenfeld, are well underway with their 2016 field season. As of February 10th, 38 ovenbirds have been captured and equipped with Lotek radio tags. Eight of these birds were recaps from last year that had geolocators on through the previous migratory season.

Photo of Robyn preparing an ovenbird for its radio debut. Photo by Kiirsti Owen.

Photo of Robyn with an ovenbird on the experimental plots. Photo by Mer Mietzelfeld.

For now we're focusing on much smaller movements, measuring the Ovenbird's home range using telemetry to connect with the radios on their backs. Next we will identify their home range and conduct insect counts on their territories. Both women are working hard and enjoying their field season the Jamaican way.