Case Study: Land Use Modeling in Northwestern Virginia

Challenge

Land use changes such as urbanization (the formation of cities), agriculture, and deforestation contribute to global environmental change. These kinds of changes also impact the ecosystem functions that humans rely on, like healthy soil and clean water. This is especially true in Northwestern Virginia, where a growing population has led to a greater demand for resources and changes to how lands are used.

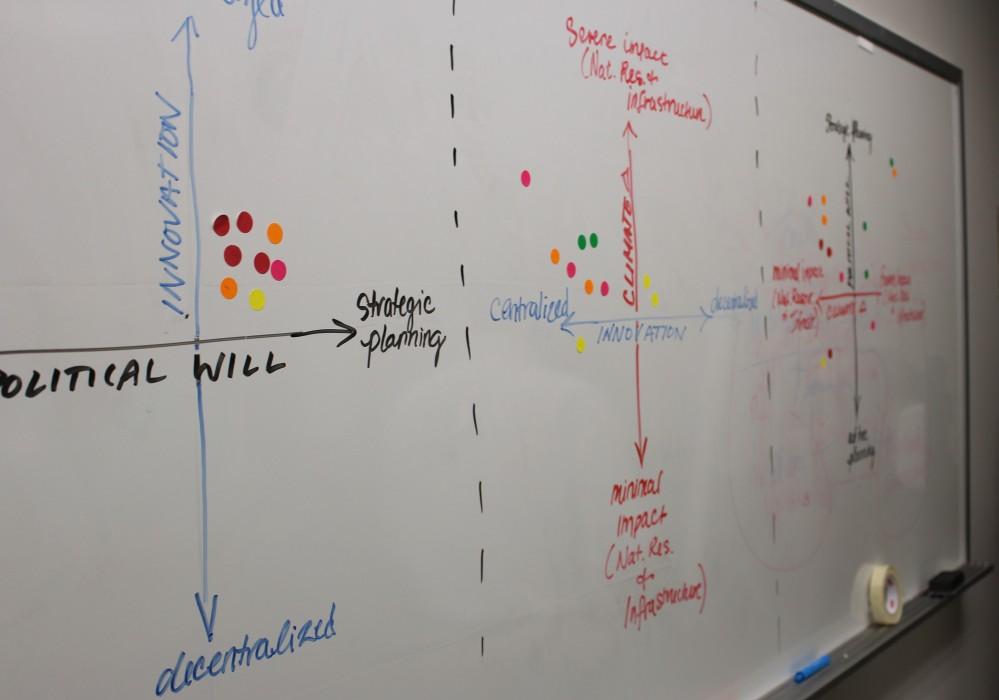

Strategic planning — planning that balances the needs of humans and ecosystems — is key to preparing for change. However, if planners lack information to help them strategize for future land use, they are more likely to allow reactive development patterns which can cause more dramatic changes to the landscape.

This case study explains how scientists from the Changing Landscapes Initiative developed a land-use model for Northwestern Virginia to inform strategic planning with a 50-year outlook. The model is based on potential future scenarios for the region that were developed with community input.

Approach

To build a land-use change model, CLI scientists begin by comparing digital maps of land cover from different years. They record locations where one type of land use has changed to another. For example, they note where grassland turned to roads or buildings (development), forest turned to grassland, grassland to cropland, and so on. These are known as land-use transitions.

Next, they look at “drivers of change” — factors that influence changes in land use. Drivers of change can include:

- Topography: Steep slopes are not ideal for cities; river floodplains have rich soil for growing crops

- Socioeconomics: Population density (the number of people living in an area) and income may impact the amount and location of buildings, roads, power supplies and other infrastructure

- Planning decisions: Zoning and designated protected areas affect how land can be used

By comparing land-use transitions with drivers of change, CLI scientists can model patterns and estimate how likely each type of land-use transition is to occur at any given location.

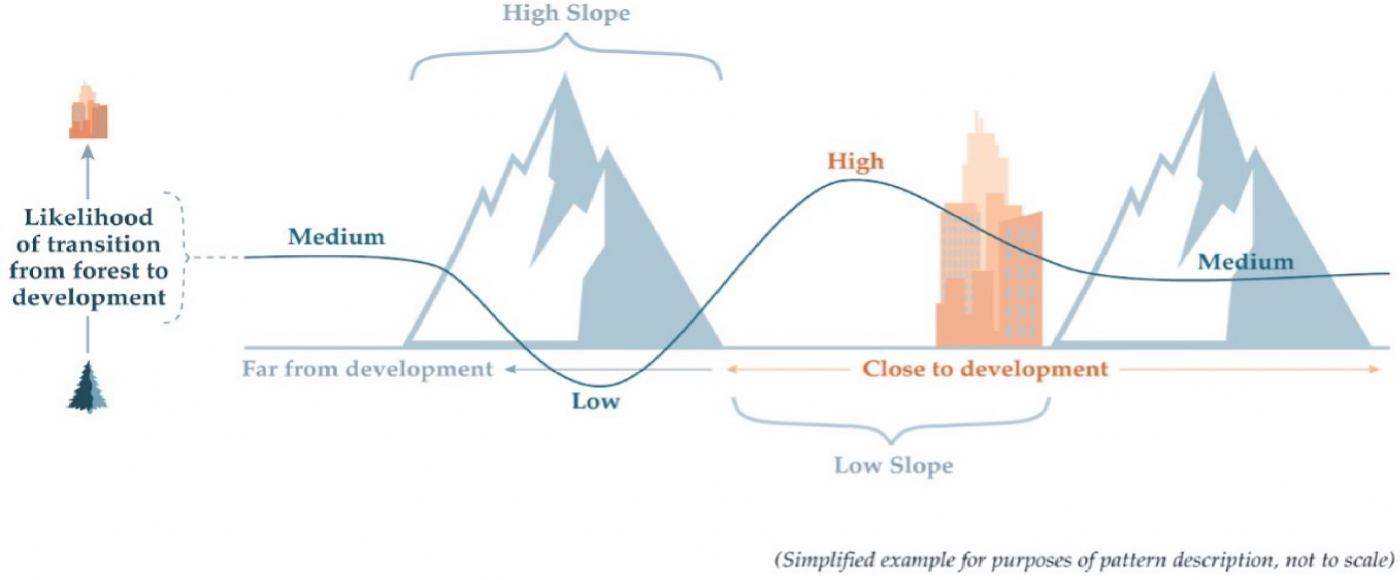

Applying this Approach in Northwestern Virginia

For Northwestern Virginia, CLI scientists compared maps of land cover from 2001 and 2011. Their land-use model produced many insights about Northwestern Virginia. One example focused on the slope of the land and areas with existing development. The land-use model showed a higher probability of forests transitioning to development in areas where the land has a low slope or incline. This makes practical sense – people are more likely to build homes on flat land (low slope) than on the side of a mountain (high slope). They also found that most new development occurs near existing development.

Considered together, the most likely place for forest to turn into development in Northwestern Virginia is on flat ground near an existing city. The least likely place is on a steep slope far from an existing development. CLI’s model considered this information, along with the other land-use transitions and drivers of change, to create its final projections.

The model uses this information on where change occurs along with data on how much change will occur to make future landscape predictions. If only a small amount of development is expected to replace forest, for example, that change should occur where it is most probable — in places with low slopes near existing cities. However, if the model predicts a lot of development, then areas with higher slopes near existing cities might change as well.

This land-use model simulates the future if things continue as they are (business-as-usual). CLI scientists also aimed to discover what might happen to the landscape if conditions change.

Incorporating Future Scenarios

Scientists altered the business-as-usual model to illustrate four more future scenarios developed with stakeholder input. The four scenarios were based on population growth (high or low growth) and community attitudes toward planning for land use (strategic or reactive planning).

- Scenario 1: High Population Growth + Strategic Planning

- Scenario 2: High Population Growth + Reactive Planning

- Scenario 3: Low Population Growth + Reactive Planning

- Scenario 4: Low Population Growth + Strategic Planning

If the area’s population grows, more housing would be needed. To simulate this change in the land-use model, CLI scientists increased the amount of development growth based on projections of regional population growth.

In scenarios with strategic planning that conserves land, new developments would be built closer to existing city services. In a reactive planning scenario, development is more likely to expand outside the city and into more rural lands.

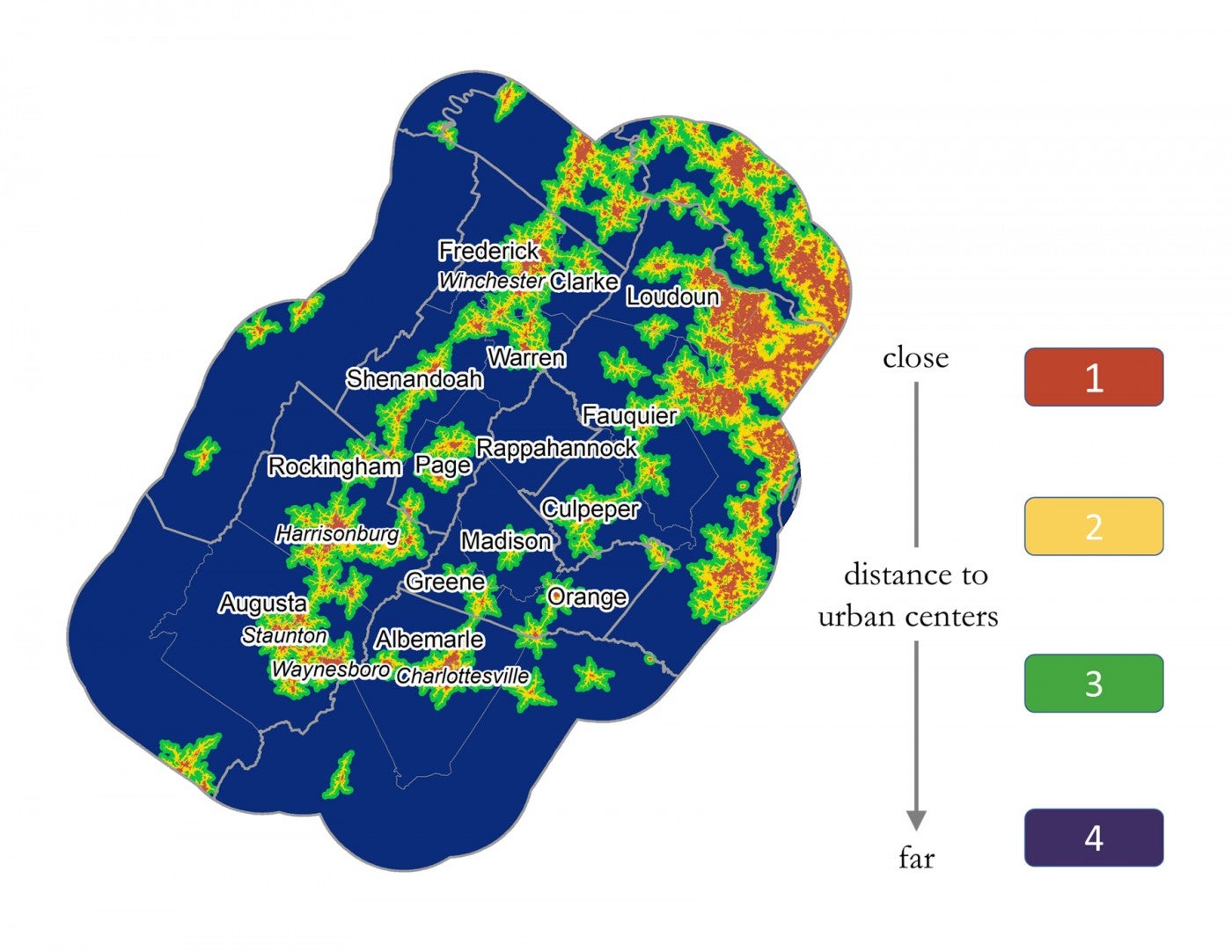

To simulate these differences, CLI scientists created a map that defines a set of four zones based on travel time to city centers.

Scientists layered this map over the probabilities made earlier — where land transitions are most likely to occur based on the slope of the land and the proximity to existing development. Then, they altered those likelihoods of land transition based on each location’s distance to a city center.

In a reactive planning scenario, the model projects a higher chance of development in zones 3 and 4. This places development farther from existing cities, with more impact on largely intact forests and ecosystems. In a strategic planning scenario, the forest most likely to turn to development is in zones 1 and 2, near existing cities. This protects forests in the larger zones 3 and 4 from fragmentation.

Results

CLI scientists put all these parts together to model different possible futures for Northwestern Virginia. Explore the map below to compare two of the region’s potential future landscapes.

Map Instructions: Use the slider button at the bottom corner of the map to place strategic growth on the left and reactive growth on the right of your view. Use the bookmark button next to the slider to zoom in on notable locations in the region.

Future Uses

The model creates simulations of future landscapes. It shows how land cover might change based on how communities plan and how population growth shifts over time. But CLI scientists can take the model a step further. They can analyze the impacts each land simulation will have on ecosystem services, such as water quality, habitat connectivity and agricultural production.

Local planners, conservation groups and policymakers can use that information to understand how decisions they make today could impact the future. How might land use, ecosystem health and quality of life change? In this way, scientists and communities can work together to build a vibrant, sustainable future for the health and well-being of people and wildlife.