2019’s Conservation Stories Worth Celebrating (Part One)

Saving species is what we strive to do every day here at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. As the year winds down, we’re reflecting on some of our biggest conservation success stories of 2019.

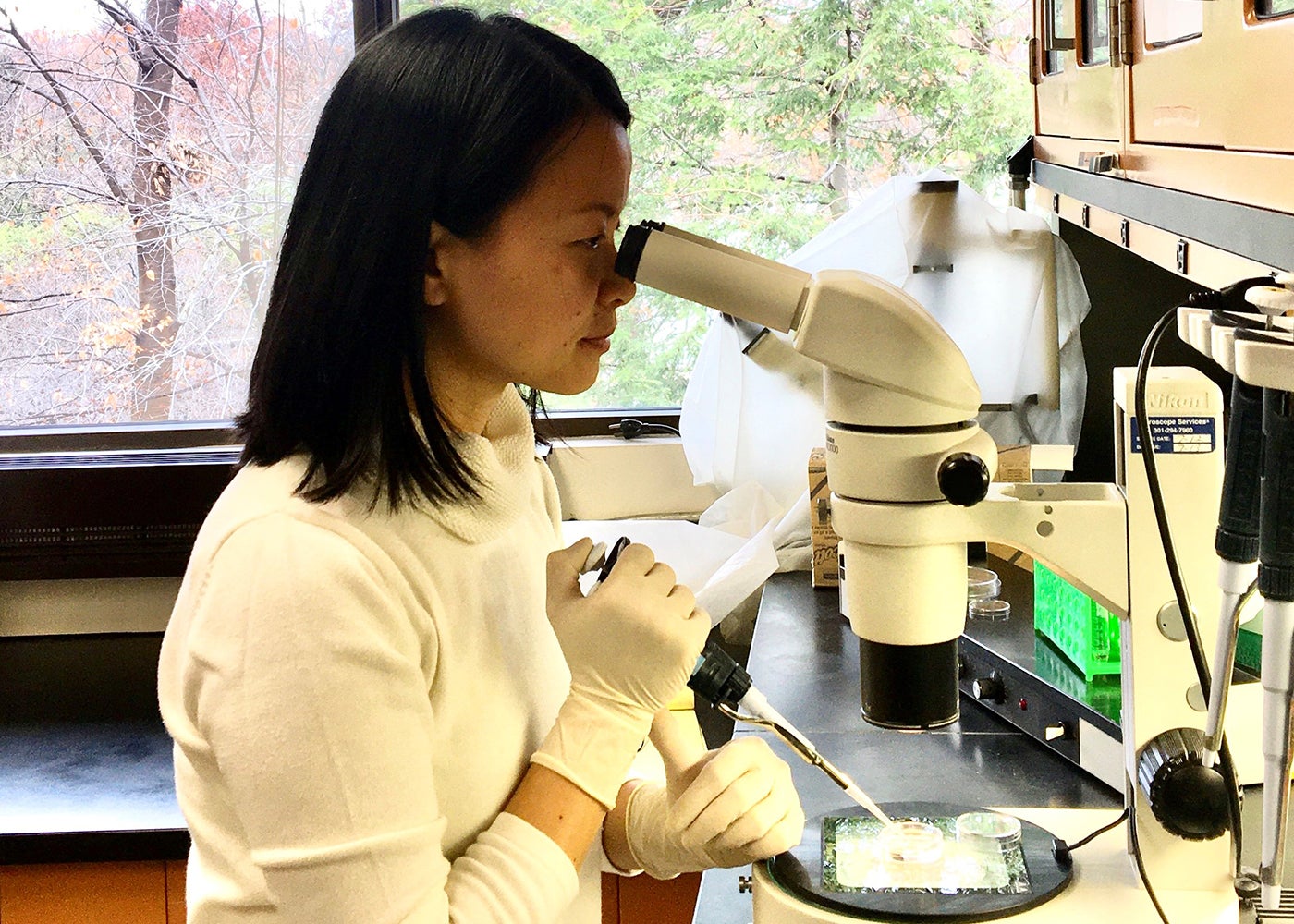

Just add water: a new proof-of-concept for tissue preservation

With the help of sugar and a microwave, Smithsonian scientists successfully preserved living ovarian tissues from cats above freezing temperatures. They adapted the concept from invertebrates (like brine shrimp) that survive dry conditions by flooding their cells with trehalose, a type of sugar. The sugar forms a stable, protective glass within and around the cells, preserving them until water is reintroduced.

Researchers infused ovarian tissues from cats with trehalose, then slowly dried the tissues using a microwave. They stored the dried tissues in a standard refrigerator for about a day, and then revived them by adding water. The rehydrated tissues maintained their structure and basic functions, including DNA transcription (a basic but important cellular process).

Scientists have been storing living biomaterials (eggs, embryos, sperm and gonadal tissues) for decades using cryopreservation, which involves freezing them in liquid nitrogen or special freezers. But it’s an expensive and resource-intensive process. This study is the first to show that dehydrating living ovarian tissues for long-term storage at room temperatures is possible. With this initial proof of concept achieved, the team is shifting their focus toward refining their techniques and improving tissue resilience.

If samples can be dried and stored this way, scientists around the world could more easily preserve reproductive tissues and support wildlife conservation. Their findings could also one day help human patients by providing a less expensive and more convenient method of storing ovarian tissues for procedures like in vitro fertilization.

The Next Chapter in Giant Panda Conservation

Giant panda fans far and wide said a bittersweet goodbye to Bei Bei in November. As part of the cooperative breeding program with the China Wildlife Conservation Association, all giant panda cubs born at the Zoo move to China when they turn 4 years old. The majority of giant pandas under human care live in China, and the best genetic matches for Bei Bei to breed with as an adult live at the China Conservation and Research Center for the Giant Panda’s (CCRCHP) bases.

After a week of farewell celebrations, the 4-year-old panda boarded a nonstop flight to China and has since settled in to his new home at the Bifengxia panda base.

Flowers and forest health

In July, citizen scientists working with the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute discovered a rare purple fringeless orchid (Platanthera peramoena). This flower is nearly extinct in the commonwealth of Virginia, where it’s estimated that fewer than 1,000 remain.

Purple fringeless orchids need wet soil to grow and are in decline throughout their range, where wetlands have disappeared. The citizen scientists found four purple fringeless orchids in bloom during their routine survey on a private farm. The orchid surveys are part of a pilot program exploring the potential for orchid species diversity and abundance to serve as an indicator of forest health.

Hide and seek: an inventive way to track down wood turtles

Finding a turtle in a forest can feel a lot like searching for a needle in a haystack, but Smithsonian researchers found a high-tech shortcut that makes searching for wood turtles easier and cheaper. It’s called environmental DNA, or eDNA.

Scientists collected water samples from streams where wood turtles might live. Then, they used a very sensitive filter to look for eDNA from biological traces that wood turtles leave behind – like feces, urine, shed skin secretions and fertilized eggs. They found bits of wood turtle DNA in samples from 17 different streams. Researchers visited those streams to confirm the accuracy of their results and found wood turtles in each area that eDNA indicated they were living.

Wood turtles are endangered and elusive. It can take years to become good at finding them in the wild, and training researchers and managers to find them is expensive. This new eDNA survey method is easier, cheaper and could one day allow scientists to track wood turtle distribution in real time.

Related Species: