The Full Annual Cycle of Migratory Birds

The Full Annual Cycle of the Gray Catbird

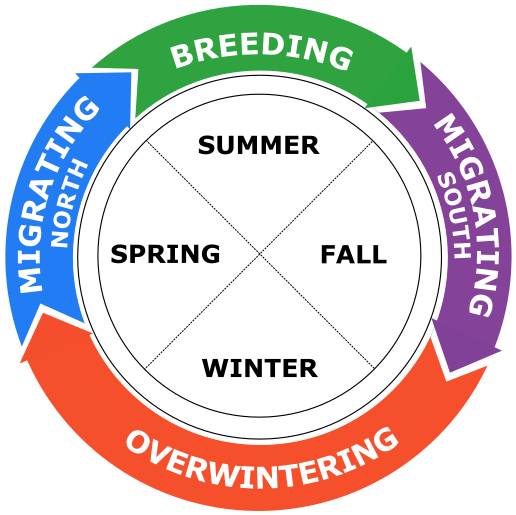

To understand how birds interact with their environment, we have to consider their full annual cycle. The full annual cycle describes a bird’s ecology across the year. A migratory bird’s annual cycle can be divided into four phases: breeding, migration away from the breeding grounds, a stationary period between late fall and early spring (the overwintering period) and migration back to the breeding grounds. During each phase, birds may live in different habitats or have different needs.

To illustrate the full annual cycle of migratory birds, we will take a closer look at the gray catbird. The gray catbird is a songbird that is common to wild areas, suburbs and cities across most of the continental United States during the spring and summer months. These birds are called catbirds, because their distinct call sounds a bit like a cat’s meow. When singing, the gray catbird is a mimic—its song is a collection of sounds it has heard throughout its life. Catbirds can be found in many different habitats, so scientists at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center have been closely studying catbirds for more than 20 years in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area. They have used many of the tracking technologies you will explore in this set of lessons to research the gray catbird’s annual cycle.

Breeding

Catbirds begin arriving in Washington, D.C., in late April and early May. When they first arrive, there are a lot of catbirds, and the city is full of their songs. Many of the catbirds we see live far north of the city and are just stopping through during their migration. Within a week or two, only the birds that will stay for the whole summer are left in the area. The catbirds that are still here use their songs to stake out territories for building nests.

Female catbirds build their nests in dense shrubs using thin twigs and grasses. They often weave bits of colorful plastic they find into their nests. Once the nest is complete, the female will lay one to six bright, turquoise-green eggs in the nest. She incubates the eggs, sitting on them to keep them warm, for about two weeks. During this time she has to spend most of her time on the nest, so she is vulnerable to predators. When the eggs hatch, the nestlings (birds that have hatched but have not left their nest) emerge helpless with closed eyes and no feathers. Both parents quickly get to work feeding the nestlings. The parents and young feed on a variety of insects during this time, especially caterpillars. This high-protein diet is necessary, because the nestlings have to grow to the same size as their parents before leaving the nest—a period of less than two weeks!

Once the nestlings are big enough and have grown the feathers they need to fly, they leave the nest. This process is known as fledging. At this point, the young catbirds are called fledglings, and they will join their parents in a hunt for insects to eat. The fledglings are still very weak and need to gain a lot of weight to survive. They are also not great flyers yet and are just beginning to get used to the new world they have launched into. This makes fledglings an easy target for predators, especially outdoor cats, which often spend time hunting for birds in suburban gardens. Most of the fledglings won’t survive for more than one week. After a few more weeks when they are strong enough, the fledglings that survive will leave their parents to explore their surroundings.

Migration

The environment changes a lot over the course of the summer. Catbirds must shift their diet with the changing season to get ready for migration. By the end of the summer, there are fewer caterpillars and other insects to eat. Luckily, the plants that flowered in spring and early summer will begin to produce berries. Adding fruit to their diet helps catbirds gain a lot of weight in the form of fat. This fat acts like a rechargeable battery during the catbirds’ migration—the energy they get from the food that they eat is stored in the fat and provides the power for their migratory journey.

Based on tracking data, including light-level geolocator tags, we know that catbirds from different breeding grounds make their fall migration to different locations. The routes the birds take during migration also differ, even among birds that leave from the same breeding location. For example, some of the catbirds we have tracked from Washington, D.C., followed the Atlantic coastline, while others traveled along the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains—a long mountain chain that runs from Georgia to Maine.

The amount of time birds spend migrating also varies by individual. Some of the birds we have tracked have taken several weeks to complete their journey, while others make the trip in less than one week. Some catbirds even stop for a long time before completing their migration. One of the birds we tracked stopped in the Appalachian Mountain foothills for more than a month before continuing its journey!

Overwintering

Using tracking data, we have found that catbirds in Washington, D.C., mostly travel to Florida and Cuba. Tracking data has shown that catbird populations from the midwest and western United States travel to the southern coast of the United States and to Mexico.

The gray catbirds’ winter habitats are very similar to the habitats where they spend their summers. Most of the catbirds we have tracked overwinter in habitats with a lot of shrubs. These habitats tend to have a lot of cover to help catbirds avoid predators and a lot of berry-producing plants and insects to supply catbirds with food. If catbirds stayed in the north over the winter, their food supply would be very limited and most of them would not survive.

The climate in areas where catbirds overwinter tends to be mild and comfortable, because it is closer to the equator than the areas where they breed. By spending the winter in the south, the catbirds are not exposed to the dangerous cold of northern winters.

As spring approaches, the catbirds start to become restless. Their sleep cycles change, and they start foraging for food later in the day. The catbirds gain a lot of weight again, this time to power their migration back north. If they stayed healthy through the winter, stored enough energy in the form of fat and survive their journey north, they will return to their summer range to breed.